I am a patient with recurrent throat cancer and an end-stage diagnosis, although I’m currently in remission. This means that I live in a liminal world, a thin place where both life and death are vividly present. In trying to learn to live there, I have been thinking about hope.

What is hope? Hope is more than just wanting a future uncertain outcome, hope cherishes that outcome. Hope is a principal theme in palliative care, the branch of medicine most applicable to the end of life. It is one of the three theological virtues of Christianity. I am studying hope to get leverage on this question: What should I hope for?

To recap my story: I was initially treated with 35 sessions of radiation. My redoubtable tumour battered through that and surged back last fall. Its location made the tumour inoperable. ‘Inoperable’ sounds like a technicality, as in, “the pass was ruled incomplete because an ineligible receiver was downfield.” Inoperable meant: “the tumour is growing into the root of your tongue and, yeah, we can cut, but you will lose your ability to speak, take food by mouth, or keep infections out of your lungs.” My surgeon gave me a “months, not years” prognosis, with no treatment options.

My wife, dog, and I left home in our car, cancer refugees wandering in search of care. We were searching for information about treatment options and places that would supply treatment, given my insurance. The result was that we learned about pembrolizumab and found an oncologist who helped me get access to it. Against the odds, it’s reducing the tumour.

But does this mean I will be cured? I doubt it, and my doctors are not telling me that. That is a statement of hope, not despair.

Dr. Isaac Kohane has written a beautiful essay on the illness of his wife, Heidi Kohane. Isaac wrote that at some point in her treatment,

My colleagues at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute [Kohane is a professor at the Harvard Medical School] told us grimly that the prognosis was so poor, standard chemotherapy could not help us.

Undaunted, Heidi pressed for an alternative, and she joined a clinical trial of pembrolizumab.

Two months after Heidi entered the… trial, her tumours started to melt away. The doctors were beside themselves with joy… Heidi’s scans remained, tumour-free, and within a few months it felt as if the cancer had just been a bad dream… But more than three years after her diagnosis we learned that the cancer had recurred. This time, nothing worked. As the Sabbath left us one beautiful fall evening [Isaac is an observant Jew], so did Heidi.

Heidi’s journey was so close to mine. My view is that, contrary to my surgeon’s prognosis, like her, I may have a few years. What should I do with such a miraculous gift? This depends on what I can hope for. That must sound odd. I imagine you telling me, “You have cancer: you are entitled to hope for whatever you want.” I don’t see it that way for two reasons.

First, I should not hope for anything that requires magical thinking. For example, I want to be cured, but I won’t indulge the magical belief that visualizing the destruction of the tumour may help destroy it. What’s wrong with a bit of magical thinking? I’ve tried to live as a scientist, and I don’t want to betray that here at the end. A cardinal scientific virtue is “no bullshit.” Good writing is the practice of that virtue. Of course, even though I strive to write what I sincerely believe, much of it is bullshit. Writing is an interminable cycle of winnowing out bullshit. Trying to write something I don’t believe in is self-induced writer’s block.

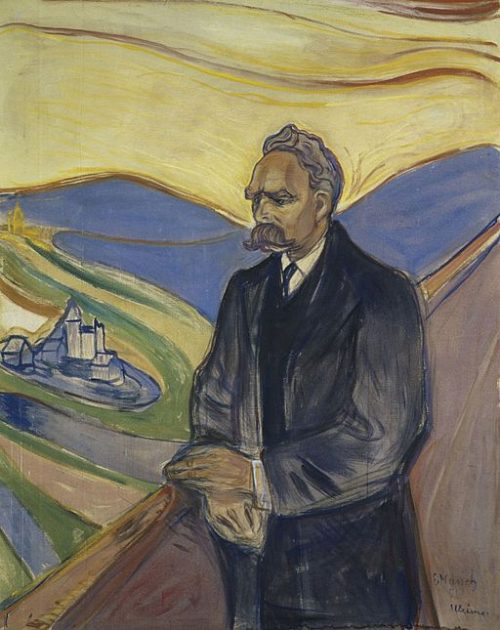

The second reason to worry is that to hope is to cherish, that is, to deepen your attachment to an outcome. Cherishing the hope of a miracle can weaken you and exposes you to pain. This, I take it, is why Nietzsche was so hostile about hope.

Hope. Pandora brought the jar with the evils and opened it. It was the gods’ gift to man, on the outside a beautiful, enticing gift, called the “lucky jar.” Then all the evils, those lively, winged beings, flew out of it. Since that time, they roam around and do harm to men by day and night. One single evil had not yet slipped out of the jar. As Zeus had wished, Pandora slammed the top down and it remained inside. So now man has the lucky jar in his house forever and thinks the world of the treasure. It is at his service; he reaches for it when he fancies it. For he does not know that that jar which Pandora brought was the jar of evils, and he takes the remaining evil for the greatest worldly good–it is hope, for Zeus did not want man to throw his life away, no matter how much the other evils might torment him, but rather to go on letting himself be tormented anew. To that end, he gives man hope. In truth, it is the most evil of evils because it prolongs man’s torment.

Nietzsche is wrong, but not obviously so. Some people press hope on cancer patients. They say, “You can’t go on without hope,” in urgent, earnest tones. Oh, really? Nietzsche persevered, and so can I. That said, I’ll never tell a friend that I don’t need hope, because I don’t want to hurt them. Their words are meant kindly; they fear that I’m in despair. They fear losing me, and their urgency is a measure of their love.

If you are tempted to urge someone to hope, it might be the right thing to do. Consider, though, that the patient may be trying to steel herself to accept what will come and finish her life with dignity based in fortitude. She may believe that cherishing the possibility of a cure would sap energy from her commitment to struggle. Listen carefully to the patient, and give her space to find her best path.

God willing, my future will be similar to Heidi Kohane’s. I’ve outlived my surgeon’s prognosis, and I am playing with house money: each additional month of life is an unexpected gift. I am with Nietzsche and the commitment to struggle, with this dissent. I have hope, because unlike Nietzsche, I do not just live for myself. And you don’t either. I’ll discuss this in future posts.