How can we tell if we are making progress in improving health? One common way is to study change over time in life expectancy. But the dynamics of life expectancy are complex. Even if a population as a whole is living longer, the story may be different for subgroups within the population. And when you try to compare subgroups on historical records of change in life expectancy, there is a possible problem called lagged selection bias. The purpose of this post is to explain it.

The basic story about life expectancy is inspiring. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, for the world as a whole, and for most nations most of the time, people have been living longer and healthier lives.

But as Hans Rosling illustrates so effectively, there is a lot of variation in historical trajectories for life expectancy. For some societies in some periods, life expectancy falls: see, for example, how devastating the Great Leap Forward was for China.

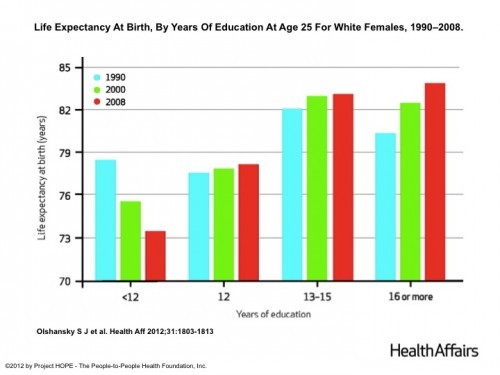

In some 2013 posts (here and here), I raised concerns about possible adverse life expectancy trends for poorly educated US women (see also Aaron). The concerns were based on data like these from Olshansky et al.:

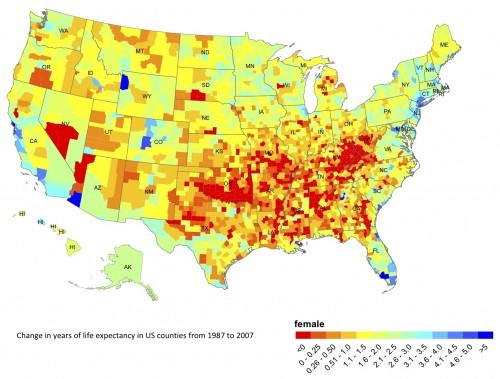

Relatedly, Christopher Murray and colleagues reported declines in female life expectancy in poor and rural US counties.

In my posts, I was concerned that these women might be experiencing worse health as a result of the increasing adverse social conditions affecting less educated workers. I had in mind the sharp decline in life expectancy in the countries of the former Soviet Union during the social and economic turmoil following the collapse of communism.

Life expectancies dropped steeply in the 1990s, and several countries have yet to recover the levels noted before the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Cardiovascular disease is a much bigger killer in the [former Soviet Republics] than in western Europe because of hazardous alcohol consumption and high smoking rates in men, the breakdown of social safety nets, rising social inequality, and inadequate health services.

I remain concerned about the possible health effects of increasing US economic and social inequality. But an article by Jennifer Dowd and Amar Hamoudi shows that we need to be exceedingly careful in interpreting differential trajectories in life expectancy.

Consider the status of being a woman with less than a high school education. In 1940, that was about half the female population. A woman who didn’t complete high school was disadvantaged relative to her peers, but not dramatically so. In 2010, however, 90% of women complete high school and the women who don’t are a much smaller and more disadvantaged group. As Dowd and Hamoudi put it, comparing the life expectancy of women who complete high school in 1940 and 2010

is akin to comparing average temperatures for the entire U.S in 1990 to only those for Alaska in 2010, and describing the difference as a “decline.”

That is, it is possible that life expectancy has actually increased since 1980 for both advantaged and disadvantaged women, even though advantaged women have notably longer life expectancies both in 1940 and in 2010. What’s happened is that having less than a high school education is a better marker of social disadvantage and selects a less healthy group of women in 2010 than in 1980.

Something similar could explain part of the apparent decline in life expectancy for women in rural counties. Many of those counties have lost population, and the group most likely to leave may be those with greater social advantages. Having more education may give you access to jobs in better markets. To get a college education, you are likely to go from a town like Chilicothe OH to a city like Columbus OH, and with your degree to jobs that aren’t available back home. Better education gives you mobility, so when women are rapidly becoming better educated, rural residence might increasingly become a marker of female disadvantage.

The possibility of lagged selection bias doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be concerned about the health effects of social disadvantage, including lack of education. Lagged selection bias can only occur when the health effects of social disadvantage are real and strong. But it should make us cautious about concluding that things are getting worse over time for a disadvantaged group.