This post has good news about my treatment. But in cancer, even good news can pose a challenge.

To appreciate how good the news is, let’s go back to April 2021 and the meeting with my surgeon when I learned that my neck cancer was recurrent. He gave me an end-stage prognosis with a life expectancy in months, not years.

Since then, I have started treatment with an immunotherapeutic drug, pembrolizumab. This did not, in and of itself, change my life expectancy much. The clinical trials data show that only about 1 in 5 patients with recurrent head and neck cancers respond to this drug. And please note: ‘response’ rarely if ever means ‘cure.’ Successful immunotherapy would likely be a few years of remission, followed by another and likely fatal recurrence. But relative to how things looked in April, that would be wonderful.

However, a piece of good news is that I have a biomarker that puts me in the group most likely to benefit from immunotherapy. And here is even better news: five weeks into treatment, I have experienced a significant drop in pain. It’s been two weeks since I have had to take hydromorphone, the powerful painkiller I was previously taking every four hours. I haven’t taken any pain medications today, which means that the ulcer on the inside of my throat has healed. And I have regained 5 of the nearly 60 pounds that I had lost since my diagnosis. All this suggests that I am one of the 1 in 5 recurrent head and neck cancer patients who will experience a remission with pembrolizumab.

And yet, despite this good news, my mood crashed. For a few days, I felt pinned to the couch by dread and loss. I was feeling physically better and psychologically worse than I have felt in 18 months. What was this about?

I have had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder since I was an adolescent. A few days of sadness isn’t depression — depression is a state that persists for weeks — but this felt like a preliminary tremor to an episode. Why should it flare now?

There are too many possible explanations.

First, I could be feeling depressed because cancer may be a cause of depression. Half of all cancer patients have mental health concerns (this also happens to patients with many other serious illnesses). Cancer hammers numerous body systems, including the brain. Caring for yourself with cancer is challenging under the best of circumstances. I cannot imagine how difficult it would be if I experienced a prolonged depressive episode.

Could depressed patients be more likely to develop cancer? The evidence here is less convincing. Still, there might be some physiological cause that can predispose us to develop both depression and cancer. I have previously discussed how cancerous cells must defeat the immune system for a tumour to develop. Depression is associated with disruption of the hormonal cycles related to our circadian rhythms and our responses to threat or stress. These hormones have complicated and profound effects on the immune system. Some theorists hypothesize that problems in the immune system may cause depression. So perhaps immune system dysregulation can increase your risk of developing both depression and cancer.

Finally, perhaps my twinge of depression was the result of the new medication. Pembrolizumab belongs to a class of drugs called monoclonal antibodies (that’s what the final ‘mab’ syllable refers to). The drug works — when it does — through its impact on the immune system. As noted, depression is associated with dysregulation of the immune system. There is evidence that other monoclonal antibodies can trigger depression. So perhaps this brief depression was a side effect of the new treatment: maybe pembrolizumab is changing my immune system in a way that triggers depression.

Given all these possible explanations, it is impossible to identify the specific cause of my mood swing. Obsessing about it will accomplish nothing.

Moreover, it distracts me from a more important question. In the best case, immunotherapy is likely to deliver me just a few years of remission. Yes, this would be fantastic. But it’s much less time than I thought I had before my cancer was diagnosed.

Therefore, I’m focused on this question: what should I do with the limited time I may have?

That’s too big a question for this post. What I want to talk about now is, what role should my emotions play in deliberating on how to spend my remaining life?

In my cancer journey, I’ve kept a tight grip on my feelings. The other challenges in your life don’t go away just because you develop cancer. You still have to cope. As the U.S. Marines say, SITFU (Suck It The Fuck Up). On this point, the Marines stand at the pinnacle of the Western tradition.

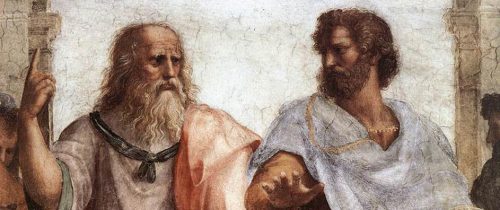

Here is Plato, in The Republic, Book 10 604b-d:

Socrates: “it is best to keep quiet as far as possible in calamity and not to chafe and repine, because… it advantages us nothing to take them hard and our grieving checks the very thing we need to come to our aid as quickly as possible in such case.”

Adeimantus: “What thing do you mean?”

Socrates: “To deliberate about what has happened to us, and… to determine the movements of our affairs… in the way that reason indicates would be the best, and, instead of stumbling like children… and wasting the time in wailing, And shall we not say that the part of us that leads us to dwell… on our suffering and impels us to lamentation… is the irrational and idle part of us, the associate of cowardice?

There is wisdom in this. But I question Socrates’ view that in calamity, the emotions are forces of cowardice and immaturity that need to be quelled to clear the ground for proper deliberation. Emotions are more than just the passions that disable or motivate us. Emotions are part of how we perceive value in the world, how we appraise what matters for our well-being.

What is the appropriate response to a cancer diagnosis? It’s more than just having the belief that things are bad. If you haven’t registered your situation in your gut and your limbic system, do you fully understand it? Have you honestly faced where you are? We can, of course, be in error in our emotional perceptions, but the same is true about our vision. Even when our eyes deceive us, we do not pluck them out.

Martha Nussbaum writes that,

Instead of viewing morality as a system of principles to be grasped by the detached intellect, and emotions as motivations that either support or subvert our choice to act according to principle, we [should] consider emotions as part… of the system of ethical reasoning.

In deliberating about what I should do with the time I have left, I shouldn’t suppress my emotions. To intelligently discern my best course of action, I need to understand what matters to me, and part of that is sorting out how I feel about where I am. I’ve got cancer: It’s ok to let the sadness rip.

When I framed my grieving as depression, I pathologized it. Don’t get me wrong: If I need to, I will go back to psychotherapy. But there’s nothing irrational about being deeply sad about cancer. I’d worry more if I didn’t feel that way.

In the first weeks of immunotherapy, my health surged and revived my hope. But having hope gave me something to lose. Paradoxically, it was easier to be The Hard Guy when I thought there was only darkness ahead. Now there is some light, and I can loosen my grip. But in that light, I see my forthcoming loss more clearly.

So be it. My grief helps illuminate what is most valuable in my life, and this is the light in which I should deliberate.