We construct life stories to present ourselves to the world, and the narratives we choose matter. A cancer memoir, like this one, tells a life story. So how does cancer figure in mine?

Part of the normative cultural frame for cancer memoirs is that cancer is an enemy. President Nixon declared war on Cancer. The Susan G. Komen Foundation has endlessly promoted the trope that breast cancer patients are fighters.

More than once, when I have told friends about my diagnosis, they immediately responded, “You’re a fighter.” The phlebotomist who drew my blood this afternoon told me, unprompted, that “You are kicking cancer’s butt.”

These folks mean well, and I am grateful for their support. But in my story, I’m not fighting cancer. Why not?

First, ‘fighting’ isn’t a good metaphor for how I experience cancer. I have never been in combat, but I think I know the difference between fighting and receiving treatment.

I was once skiing a steep couloir in the Utah backcountry when the top layer of snow released, sending a foot of fresh powder rushing down the chute. If I fell, it would bury me. Somehow, I stayed upright on the flow until I reached the mouth of the couloir and could ski out of the path of the avalanche.

Another time, I capsized my kayak in rough water, 500+ meters from shore in a Nova Scotian fjord. Every time I tried to get back in the boat, the waves rolled me out again. I had enough sense to be wearing my wetsuit, but the water temperature was 7°C (45°F), and staying in it would have led to hypothermia. I tied my boat’s painter to a strap on my life jacket and sidestroked my way to shore.

In both cases, there were directly perceptible threats and physical struggles to survive. I recall my emotion during these events — not so much fear as the instant recognition of danger — followed by complete attention to and engagement in the tasks at hand.

Cancer treatment requires me to sit in a chair receiving a drug infusion. The drug binds to a receptor on the surfaces of the cancerous cells, enabling my immune system to attack the tumour. Of course, I can’t perceive any of this. I work on my laptop for an hour while the drug is pumped into my arm.

Second, cancer is a problem built into the heart of nature. How do I fight that? Let me explain.

Cancer is the breakdown of multicellularity. Humans are composites of ~30 trillion cooperating cells, with a division of labour constructed by evolution. One of the ways cells can violate this cooperation is by excessive reproduction. Athena Aktipis writes:

Cancer can be viewed as cheating within this cooperative multicellular system… cancer is characterized by the breakdown of the central features of cooperation that characterize multicellularity, including cheating in proliferation inhibition, cell death, division of labour, resource allocation, and extracellular environment maintenance.

Cheating is, of course, a metaphor; cells have no intentions. What cells have is genetic machinery that limits their reproduction to what your body needs. The immune system likewise polices the cells, attacking cancerous cells that reproduce too much. These controls maintain cellular cooperation. Why do these controls fail?

Cooperation fails because the body’s cells evolve. The maintenance of healthy tissue requires that about 2 trillion of the body’s tissues divide each day, which is hundreds of quadrillions of cell divisions over a lifetime. Each replication has a slight chance of a mutation. Given enough time, the chances are that the genetic machinery regulating cell reproduction will break somewhere in your body. We then get a population of cells with a heritable mutation that enables them to grow faster than their healthy neighbours, i.e., a tumour. In short, evolving multicellular organisms will suffer from cancer.† This is regrettable, but we wouldn’t have complex, sentient life without the evolution of multicellularity.

Cancer is woven deep in nature, but that doesn’t make it good or wholesome. It’s a terrible affliction, inflicting 9.5 million deaths globally each year, with an uncountable cost in suffering and the destruction of human capability. Although I can’t fight cancer as an individual, we have been fighting it as a species, albeit with only partial success. We have fought this war collectively across generations, and the weapon is science.

And here is my final point: I am not fighting cancer because cancer is not the true enemy. The enemies are death and suffering; cancer is just one of the myriad causes of affliction.

My calling — what I do on the laptop while the drug flows into my arm — has been to serve on another front, researching mental illness. After developing cancer, I started writing for other patients about my experience. But caring for the other wounded is ancillary; research is the path to victory.

If you are a cancer patient and the fighter self-image empowers you, stay with it, and Godspeed. But be careful. A friend who is a palliative care physician tells me that the “fighting” metaphor can be devastating for his patients, particularly for males when they near death. Fighting is the master life story for a lot of men, but you can’t intimidate cancer. These men, he says, die experiencing themselves as losers.

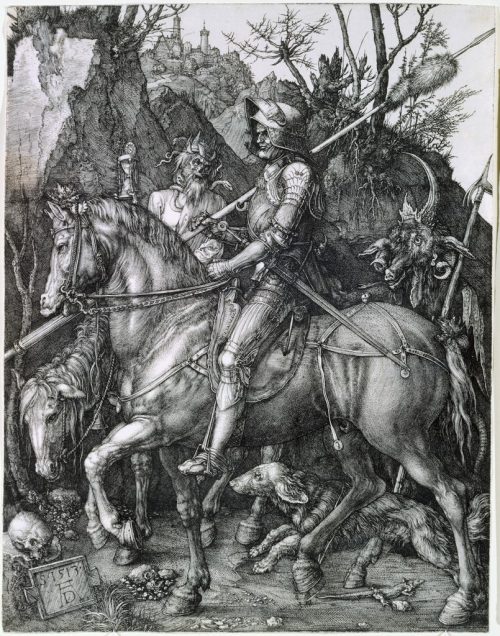

That said, here is a warrior attitude that I aspire to. In September 1944, British paratroopers attempted to seize a bridge in a Dutch town deep behind German lines. Misled by faulty intelligence and planning, they were trapped by two far more heavily armed SS Panzer divisions. Lt. Colonel John Frost and Major Harry Carlyle commanded a small group of paratroopers who had seized one end of the bridge. They were surrounded and on the point of being overwhelmed. Then (as depicted in the film ‘A Bridge Too Far’), Carlyle and Frost watched a German officer approach under a flag of truce.

Maj. Carlyle: [To the German] That’s far enough! We can hear you from there! [To Lt. Col. Frost] Rather an interesting development, sir.

SS Panzer Officer: My general says there is no point in continuing this fighting! He is willing to discuss a surrender!

[Pause]

Frost: [To Carlyle] Tell him to go to hell.

Carlyle: [To the SS officer] We haven’t the proper facilities to take you all prisoner. Sorry!

SS Officer: [Confused] What?

Carlyle: We’d like to, but we can’t accept your surrender.

[Pause]

Carlyle: Was there anything else?

Carlyle’s pretense of misunderstanding the situation, and his deadpan delivery, communicated a complete indifference to his dire peril. His pretense of courtesy — “Was there anything else?” — cloaked but did not hide his contempt for the SS officer.

Although I need to accept that cancer is how things will likely end for me, humanity will continue to fight. We will win in the end.

*In a lecture, Stephen Jay Gould once said that,

Every damn story in biology has an exception. You give a talk and someone gets up in the audience and says, ‘Your theory is great. But there is this mouse found in Michigan…’

There seems to be an exception to my claim that cancer is the cost of multicellularity. Somehow, naked mole rats never get cancer. It’s okay; I would still rather be a human.

†Moreover, the continuing evolution of the tumour may be the process that kills me. For the sake of argument, let’s assume that my current immunotherapeutic treatments halt the progression of the tumour. However, if even a small population of cancerous cells survives, they will evolve. Eventually, these cells may evolve a novel way to defeat my immune system. Then the tumour will resume its exponential growth, leading to metastases and my death.