Sometime in late 2019, an outbreak of coronavirus-related pneumonia began in Wuhan, China. The first American case was reported on January 21. The WHO and the CDC warned of an impending pandemic in late February. On March 3, David States, Nicholas Bagley, and I wrote a TIE post predicting the severity of the pandemic. In this post, I will review what we got wrong.

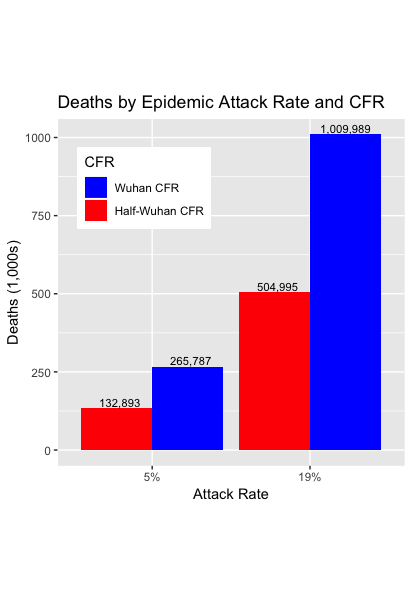

The key figure in our post is here.

The bars reflect our guesses about the epidemiological parameters driving the epidemic. Knowledge about them was highly uncertain at that time. Here’s what we said about this graph:

These numbers are shocking. Even under our most favourable scenario, roughly 133,000 people will die. Of greater concern, if we assume that US COVID-19 is half as lethal as the Wuhan data, then under a plausible 19% Attack Rate, there would be half a million deaths. Under the least favourable scenario, 1,000,000 will die.

Our prediction was wrong, but allow me to provide some context.

On the day we published that post there were only 6 confirmed US COVID deaths. There may have been other published predictions of the epidemic’s size, but I wasn’t aware of them. Knowledgable people derided us on Twitter; at least one, to his credit, wrote me later to apologize. Predictions soon appeared on other blogs. About two weeks later, for example, Richard Epstein of the Hoover Institute wrote that

The world is in a full state of panic about the spread and incidence of COVID-19.

Epstein thought that panic was unjustified because he was confident that only 5,000 Americans would die of COVID. A week later, he wrote that this was a typo and that he had intended to write 50,000 deaths. With that correction, he was only off by a factor of 20. At least we got the order of magnitude right.

Regardless, our prediction was wrong in three ways.

First and foremost, the pandemic in the US has been much worse than we predicted. The current count of confirmed deaths is nearly 1,000,000, at the top of our predicted range. Clearly, however, a BA.2 wave of COVID is coming. There is no reason to believe that that wave will be the last one and no reasonable argument that the final count — if there ever is one — will be ≤ 1,000,000. Moreover, the confirmed deaths count is a conservative estimate of the number of COVID deaths. A better gauge of the pandemic’s mortality, estimated excess mortality, exceeded one million months ago.

Second, the model we used to predict US COVID deaths was too simple. We just took a simple epidemic model and put in the estimates for the transmission rate of the infection and the age-specific mortality available from the early Wuhan data. David worked up a spreadsheet, which I translated into R over a weekend to capture the uncertainty in those data.

What was the model missing? A serious model would have tried to capture the social networks across which infections diffuse. We also missed the rapid evolution of the coronavirus, which has produced a series of new variants. Some of the new variants transmit faster than the alpha variant; others have some ability to evade the immunity conferred by either the vaccines or by previous exposure to coronavirus.

Finally, our prediction did not meet the Superforecasting standards for a good prediction, based on Philip Tetlock’s research. For example, we failed to give a specific date, as in “There will be at least X American COVID deaths as of date Y.”

When I ran the calculations for our prediction, I couldn’t believe them. The numbers of deaths were unthinkable. But the model said what it said, and we posted the results.

It is so sad that we were too optimistic.