If you have access to it, I hope you read my latest publication in Health Services Research on hospital cost shifting and productivity. It’s a commentary on a new paper by Vivan Wu and Chapin White. My paper, being a commentary, is not long. But, if you don’t have time or access, below is a summary of part of it. I plan to write more about the content on the AcademyHealth blog, probably next month. [Update: That post is here.]

The Affordable Care Act will cut the growth rate of Medicare payments to hospitals. Hospitals will respond largely or entirely by cutting costs. (Other responses like cost shifting or profit cutting are likely to be small to nonexistent. If you want to know why right now you should read my commentary in full. Following the last link would help too.) A key question is what these cost cuts do to patients’ outcomes. That is, will hospitals become more productive, converting fewer resources into the same or better health? Or will they cut costs in ways that harm patient care?

Wu and Shen found that, in response to hospital cuts required by the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, heart attack mortality increased. Each 1% cut in payment resulted in a 0.4% increase in heart attack mortality rates. Lindroth et al. found that lower hospital service line Medicare profitability was associated with an increase in mortality. I wrote,

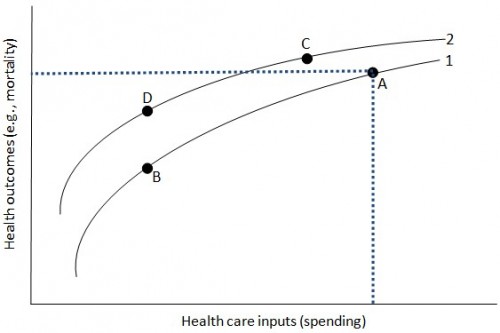

These studies suggest that hospitals that cut costs in response to Medicare payment shortfalls are unable to do so in productivity enhancing ways. This is illustrated in Figure 1 [below], which shows two hypothetical hospital production functions relating health care inputs (spending) to health outcomes (like mortality) (Chandra, Jena, and Skinner 2011). Consider a hospital operating at point A on curve 1 (the lower curve) that is then faced with a cut in inputs (Medicare payment reductions). If the hospital is unable to change its production function, it can only move along curve 1. If it then addresses the shortfall by cutting costs, it necessarily leads to worse outcomes (higher mortality): point B on curve 1. Because B is on the same production function as A, the hospital has not become more productive in converting spending to health. [Link added.]

The hope, of course, is that new payment models, like accountable care organizations and bundled payments, will encourage greater productivity. In my paper I wrote a little bit about why we might and might not be encouraged that they will do so. Suppose, for a moment, we succeed in doing so.

Returning to [the figure], reductions in cost and improvements in quality such as those [that might be] achieved by [new payment models] are consistent with a movement from point A on curve 1 to point C on curve 2. In other words, they are a combination of an upward shift in the productivity function and a downward movement along it. The former is a productivity enhancement. The latter is a trade of lower spending for poorer outcomes, holding the production function fixed.

The ACA includes both a blunt Medicare payment cut (the predicted 1.1 percent annual productivity adjustment) and designs for incentives for higher quality and better outcomes (like ACOs). Evidence suggests the former is not productivity enhancing, but hope remains that the latter may be. A key question is how the two work together. Will they move a hospital from point A to point B (lower spending with much worse outcomes) or C (lower spending with better outcomes)? Another possibility is a trade-off of substantially lower spending (relative to trend) for somewhat poorer outcomes, like point D. [Link added.]

A movement from point A to point D calls to mind what Mark Pauly wrote in Health Affairs, “Perhaps a little less quality for a lot less money might be acceptable to consumers and taxpayers, as we work to keep medical spending from siphoning off funds required for other needs.” Whether it is acceptable or not, it may be what we get.