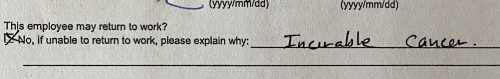

I’m fortunate to work for a hospital that provides excellent disability benefits (even in Canada, not all employers do). To qualify, I needed to get a form completed by my oncologist. Before I returned it to Human Resources, I read it.

There it is, concise and direct: “Incurable cancer.” The editor in me loves it, if no one else does. And no one would ever write it if they didn’t believe that it was true.

A pivotal scene in every cancer memoir is the event that leads to the initial diagnosis. Great writers on cancer describe it as a transition across a boundary.

Here is Christopher Hitchens reporting his discovery that he had esophageal cancer:

I have more than once in my time woken up feeling like death. But nothing prepared me for the early morning last June when I came to consciousness feeling as if I were actually shackled to my own corpse. The whole cave of my chest and thorax seemed to have been hollowed out and then refilled with slow-drying cement… It took strenuous effort for me to… summon the emergency services. They arrived with great dispatch and behaved with immense courtesy and professionalism. I had the time to wonder why they needed so many boots and helmets and so much heavy backup equipment, but now that I view the scene in retrospect I see it as a very gentle and firm deportation, taking me from the country of the well across the stark frontier that marks off the land of malady.

Likewise, Susan Sontag:

Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

The boundary between these kingdoms lies between you and me and between me and my former life. What is this boundary?

We in the Kingdom of Malady — specifically, the Duchy of End-Stage Cancer — have been through a transformative personal experience. We know things that you do not. The philosopher L. A. Paul argues that there are things that you cannot know until you experience them. Imagine that your parents raised you in a windowless room where everything was in black, white, or shades of grey. In this room, you learned to use the word ‘red.’ You might know many facts about redness, e.g., that apples are red. But until you saw a red apple and experienced redness, you wouldn’t understand ‘red.’ L. A. Paul:

[S]tories, testimony, and theory aren’t enough to teach you what it is like to have truly new types of experience — you learn what it is like by actually having an experience of this type.

Moreover, some of these experiences are personally transformative.

The sorts of experiences that can change who you are, in the sense of radically transforming your point of view… may include… having a traumatic accident, undergoing major surgery,… having a religious conversion, having a child,… or experiencing the death of a child.

If we do not know what these experiences are like, we can’t assign values to those experiences. How, then, can we make decisions that can lead us to outcomes we don’t understand? In the Duchy of Cancer, I have been offered surgery to remove my tumour, a procedure that would likely leave me unable to speak. I have no idea what being unable to talk would be like. Likewise, you have no idea what it’s like to live in a world structured by such choices.

What makes citizenship in the Duchy of Cancer a personally transformative experience? When you cross the border, at least four things happen. First, the sudden foreshortening of your life expectancy transforms how you experience time. Second, you have to suffer the disease and its treatments. The third is that death enters your room, and you have to address your fear of him. Fourth, being in the Kingdom of Malady transforms your relationships with citizens in the Kingdom of the Well. I’ll focus on each of these experiences in future posts, starting with how my sense of the future changed when that future got so much smaller.

However, if you need to experience cancer to understand it, then what is the point of the Cancer Journal? If Paul is correct, you won’t get it just from reading my words.

I hope that the Cancer Journal helps you when you cross the boundary. Paul is right: transformative life experiences take us places we cannot foresee. Yet somehow, literature takes me into the lives of people I can never be. I have experienced the flight of Hector around the walls of Troy, Nicodemus pinned by words in the night, Emma Bovary contemplating adultery, and Andrei Bolkonsky facing his duty before the battle of Borodino. Do I know what it is like to be wounded by shrapnel? Of course not. But having been there in imagination, I hope that I am more ready to learn how to face my own trial.

My goal, then, is to convey my experience to you even though, as Paul argues, I know that you can’t fully receive it. The Cancer Journal won’t provide anyone with self-help. (Except for me: I’m writing it to find my own way.) Your way to your fate will be different, but you might get some benefit watching me stumble toward mine.

If you know someone who has crossed the boundary, consider sending them a link to the Cancer Journal.