Black patients receive worse health care at US hospitals, but we are making progress: the racial gap in the quality of health care is decreasing. But James Hamblin argues that although

we have been able to improve general quality of care for a limited number of conditions in hospital settings, but the more important metric, health outcomes, remains largely unchanged.

Hamblin points to an important problem. Health care matters only as a means to achieving health and there are important racial disparities in actual health. But taking the long view, it isn’t true that race differences in health are largely unchanged.

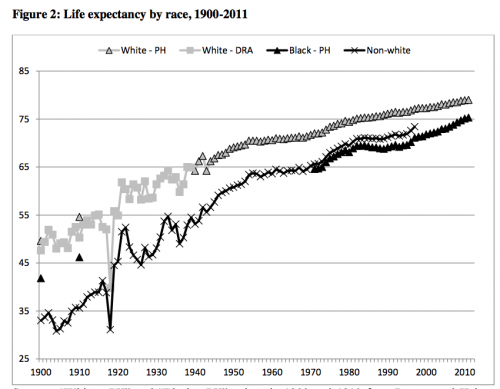

Leah Boustan and Robert A. Margo have a useful summary of the history of Black/White differences in health in the US. Here is the key graph, showing historical change in life expectancy at birth by race since 1900.

It’s startling how brief life expectancy was in 1900. There has been a lot of improvement since then. Moreover,

Since 1900, the absolute racial gap in years of life has been cut in half, and, expressed as a percentage of Black life expectancy, the racial gap has declined even further (from around 20 percent to around five percent).

So, we have made slow progress on reducing the difference in life expectancy between US Blacks and Whites. As with differences in the quality of health care, as Dr. King said,

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.

In this case, you can actually see the convergence of the arcs.

Nevertheless, an important gap remains. Boustan and Margo argue that equity in maternal and child health is critical:

racial disparities in health begin very early in life – essentially, in the womb. Early racial differences in health are also apparent in infant mortality rates. In 2011, the black infant mortality rate was twice as high as the White infant mortality rate (1,058 versus 516 deaths per 100,000 live births). Early disparities are a key factor in the emergence of chronic conditions later in life which, in turn, produce higher levels of adult mortality for the middle-aged Blacks and those nearing retirement.

Racial differences in health are an injustice: Black children are born to a disadvantage in health, they do not make it themselves. Moreover, this disadvantage is remediable. How do we know? Look at the progress we have made in the last century.

Note. There are many subtleties in using life expectancy as a measure of health. Aaron has covered this many times (e.g., here and here). In particular, historical trends for life expectancy at birth may not be the same as trends for later ages (for example, life expectancy at age 65); these differences matter for assessing racial justice. Moreover, racial groups are themselves highly diverse, and life expectancy trends also differ by gender and education, among many other factors.