I’ve gotten a number of emails asking me why I keep stressing that we need to pay attention to life expectancy at age 65, when it comes to Medicare, instead of life expectancy at birth. It’s a fair question.

People who want to raise the eligibility age for Medicare like to cite the increase in life expectancy at birth. That’s been going up fast, according to them, and, again according to them, Medicare was never intended to support people for so long.

There are problems with this belief.

Let’s take a theoretical cohort of 100 people. Let’s stipulate that the life expectancy at birth of this group is 74. In this cohort there is a baby who dies soon after birth, and there are also 25 people who live past the age of 65.

Scenario A: I manage to find an excellent treatment for what kills the baby in the cohort. It’s not perfect, but it allows the baby to live to age 50.

Scenario B: I manage to find a treatment for a common illness that afflicts elderly people, and can extend their life an average of 2 years.

In both these scenarios, I have managed to add 50 years to the cohort. So the average life expectancy at birth has increased to 74.5 years. But this, hopefully, shows you the enormous power of saving one baby or child, in that saving one infant for fifty years is the same as saving 25 adults for only 2 years. The take home message here is that treating children well does far more to increase life expectancy at birth than treating adults for illnesses that kill them.

And we’ve had remarkable improvements in the treatment of children and chronic diseases in the last few decades. Vaccines do wonders. We can treat many illnesses that used to kill children far into adulthood now. Many childhood cancers can be cured. Saving those children has resulted in relatively big increases in the overall life expectancy at birth.

In Scenario A, I have not increased the life expectancy at 65 at all! In Scenario B, however, I have increased the life expectancy at 65 a full two years. This has enormous policy implications. The increase in Medicare spending in Scenario A is $0.00. The increase in Medicare spending in Scenario B is comparatively huge. We would need to provide two additional years to all twenty-five elderly, for fifty additional person-years of Medicare.

Now, this is a fictional cohort. It explains, however, how saving a child can significantly increase life expectancy at birth, but result in little extra Medicare spending. What matters for Medicare spending is the years we have to provide it, which is exemplified by the life expectancy at age 65.

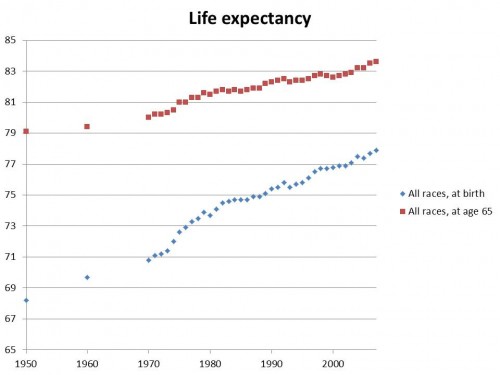

And, as I’ve shown many times, life expectancy at age 65 is not going up nearly as fast as life expectancy at birth:

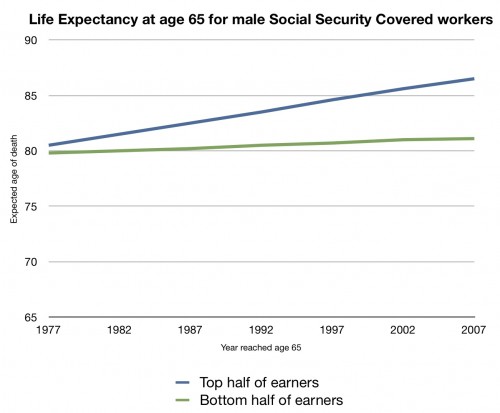

Nor is it going up the same for rich and poor alike:

In fact, it’s been pretty flat for the bottom half of earners. Remember this when someone claims that “people” are getting so many more years of Medicare than they used to.