After recent posts on murder and torture, I just had to write about good news. And this is great news. Amal Trivedi and his colleagues report in the NEJM that racial and ethnic differences in the quality of US hospital care are diminishing.

These differences have been pervasive and deeply troubling. To look at them, the authors

…assessed performance rates for quality measures covering three conditions (six measures for acute myocardial infarction, four for heart failure, and seven for pneumonia). These rates, adjusted for patient- and hospital-level covariates, were compared among non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic patients who received care between 2005 and 2010 in acute care hospitals throughout the United States.

Heart problems and pneumonia are, of course, among our major killers. Trivedi and colleagues examined an amazing 12.5 million hospitalizations. Their comparisons adjusted for a number of demographic factors other than race and ethnicity.

The researchers found that

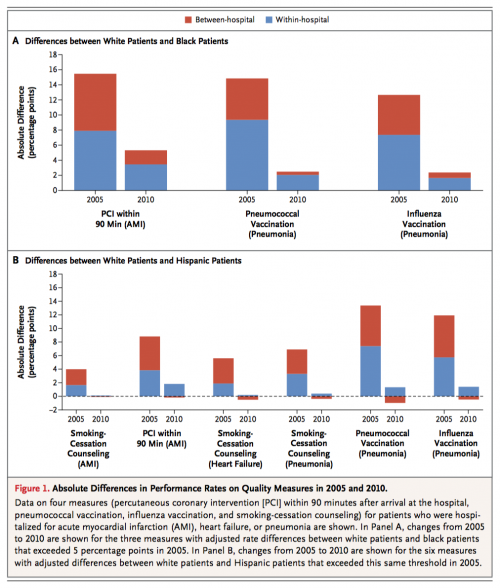

Adjusted performance rates for the 17 quality measures improved by 3.4 to 57.6 percentage points between 2005 and 2010 for white, black, and Hispanic adults (P<0.001 for all comparisons). In 2005, as compared with adjusted performance rates for white patients, adjusted performance rates were more than 5 percentage points lower for black patients on 3 measures (range of differences, 12.3 to 14.2) and for Hispanic patients on 6 measures (5.6 to 14.5). Gaps decreased significantly on all 9 of these measures between 2005 and 2010, with adjusted changes for differences between white patients and black patients ranging from −8.5 to −11.8 percentage points and from −6.2 to −15.1 percentage points for differences between white patients and Hispanic patients. Decreasing differences according to race or ethnic group were attributable to more equitable care for white patients and minority patients treated in the same hospital, as well as to greater performance improvements among hospitals that disproportionately serve minority patients.

Trivedi et al. looked at two sources of variation in the quality of care. Between hospital variation means that differences in the quality of care typically received by (for example) a Black American happened because Black patients are typically served by hospitals that deliver lower quality care than the hospitals that see more White patients. Within hospital variation means that Black patients receive receive worse care than White patients within the same hospital.

What they found was that both between hospital (red) and within hospital (blue) racial and ethnic differences in the quality of care were considerably smaller in 2010 compared with 2005.

It’s important to understand what the study does not show. We don’t know whether there have been similar improvements in the equity of ambulatory care or in areas other than heart disease and pneumonia. The adjustments for factors other than race will necessarily be imperfect, so it’s possible that some of the differences in care reflected disadvantages that couldn’t be measured. The study can’t say why the quality of care improved. Perhaps most importantly, the researchers did not look at clinical outcomes or improvements in the experience of care. This doesn’t mean there was something wrong with the study. It just means that the researchers are proceeding one step at a time.

My view is that the widely endorsed Triple Aim — better outcomes of care, better patient experience of care, better value of care — ought to be expanded to include a fourth Aim: more equitable care. We are not there yet, but we are making progress.