The following is a guest post by Allan Joseph, a medical student at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and TIE research assistant. You can follow Allan on Twitter: @allanmjoseph.

As Aaron mentioned last week, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently published a comprehensive report on graduate medical education (GME) funding in America that has set off some serious debate in health policy circles. Over the next couple of weeks, we’ll have an occasional series in which I dive into some of the issues that the report brought up, starting with this post. You can find all of the posts on the subject under the tag IOM on GME. If you have something in the report you’d like me to address, let me know on Twitter (@allanmjoseph) or via email.

For background on GME — what it is, how it’s structured, etc., this Health Affairs brief is a good place to start.

Today’s post will focus on the question Adrianna posed over at Vox: will there really be a physician shortage? Some ground rules for this post: we’re only going to focus on the question of an aggregate doctor shortage. We’ll get to questions that are about GME and its effects on the supply of physicians, as well as questions of geographic distribution or the balance between primary care and specialists, later. For now, let’s just punt on all that and deal with “physician supply” writ large. The questions here are fascinating enough.

The argument for increasing GME funding rests on the claim that America is heading towards a doctor shortage (or that we’re already there). To make that claim, you have to forecast demand for and supply of physician services, not just the number of physicians. There’s not much debate over demand, so I’ll just give you a brief overview; it’s expected to increase significantly in the next few decades due to a number of factors: the ACA expanded insurance coverage, baby boomers are aging and becoming sicker, and patients are more likely to have multiple complex conditions than ever before.

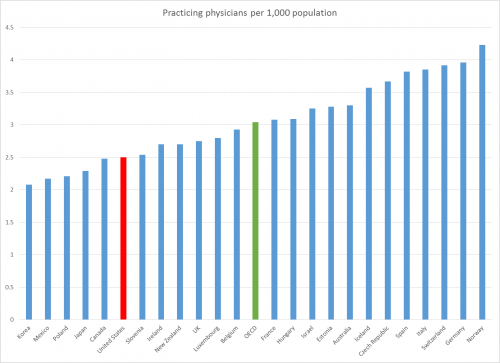

Forecasting supply is where it gets tricky. The simplest way to estimate supply is to use the physician-to-population ratio — it’s easy enough to forecast population growth and changes in the numbers of physicians. In America, the ratio is roughly 2.5 physicians per 1,000 residents and has been relatively consistent since 1995. That’s below the OECD average, with about the same physician density as Canada and fewer physicians per person than the UK, France, and Germany:

Forecasts of physician shortages tend to use historic physician-population ratios — if we needed X doctors per 100,000 Americans in the past, we’ll need roughly that same ratio in the future (not accounting for changes in disease burden). To see this in action, take a look at this projection from the American Association of Medical Colleges. Their first bullet point implicitly argues that the shortage is due to a forecast decrease in the physician-population ratio.

That’s a somewhat intuitive way to look at the problem, but it’s probably too simplistic.

To more accurately estimate supply, you also have to consider productivity. If physicians can provide their services more productively — that is, more of them per unit time — then that works as an increase in supply too. There are two broad categories in which that might happen: technology and delegation.

Technology should be construed broadly here. It could mean almost anything: new scheduling practices that result in fewer no-shows, breakthroughs in electronic records, more-effective treatments that require fewer follow-up visits (Sovaldi may be an example), economies of scale resulting from provider consolidation, in-office equipment such as ultrasounds that provide for quick diagnosis, telemedicine, or a host of other things that allow doctors to see more patients in a fixed amount of time. They might not seem like much on their own, but in combination, these types of improvements could add up to a pretty substantial increase in physicians’ productivity. The literature on this isn’t enormous, but we can ballpark some numbers of best-case scenarios that have been published. There’s someevidence to show that health IT alone can result in productivity improvements of about 5-10%. Replacing many visits with telephone calls and e-mails can reduce demand for in-person visits by 20-25%, leading to productivity increases of something less than that. Physicians pooling in larger practices could mean increases in productivity of 18%. There’s a lot of opportunity for the system to become more efficient, and it’s already happening in places. If that continues, the system could quite conceivably tolerate a lower physician-population ratio than in the past. But don’t get too excited: the research isn’t strong or wide enough to draw a strong conclusion those gains would be replicated system-wide. For example, poorly-executed health IT might harm productivity, and physicians who aren’t paid to do e-visits won’t have any incentive to become more productive that way. Those studies might also represent catch-up gains rather than new avenues for growth. The point is, it seems like a stretch to reliably estimate the magnitude of future productivity gains with a relatively sparse literature.

Let’s move on to delegation, which is a simple concept. If physician assistants (PAs), advanced-practice nurses (nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives etc.), optometrists, pharmacists, and others can also provide some of the same services as physicians, then that too is an increase in the supply of physician services. There’s a fine point to be made here, though — delegation only creates an effective increase in the supply of physician services if the services of other providers are truly substitutes for physician services. If the quality isn’t the same — or even if patients don’t perceive them to be the same — then that’s not truly an increase in the supply of physician services. If you’re a patient and you don’t see your doctor except for certain rare services or if you’re extremely sick, it’s easy to think you’re looking at a doctor shortage, even if you’re getting the same services from someone else. It’s a fine difference between a “physician shortage” and a “physician service shortage.”

That’s why this is very controversial. There’s a lot of research into the differences in outcomes and patient satisfaction, and as you might imagine, physicians’ and nurses’ groups highlight different facets of the research — nurses point out that outcomes and patient satisfaction are comparable to those of physicians, doctors point out that patients often assume these providers are doctors when they’re not, and I point out that very little of the research is an accurate head-to-head comparison. This has led to lots of battles over scope-of-practice laws in various states (Here’s a previous TIE post for more on that debate.)

There are some countervailing forces to the forecasts of increases in supply: doctors are working fewer hours than in the past, reducing supply. There are system-wide changes such as the switch to ICD-10 billing codes or increases in maintenance-of-certification requirements that could slow productivity growth. New treatments might as easily require more time from physicians. In states where scope-of-practice laws limit other providers’ ability to provide physician services — or if forthcoming research definitively shows these other providers provide lower-quality care, even if only in the eyes of patients — delegation might not increase the supply of physician services, as noted above.

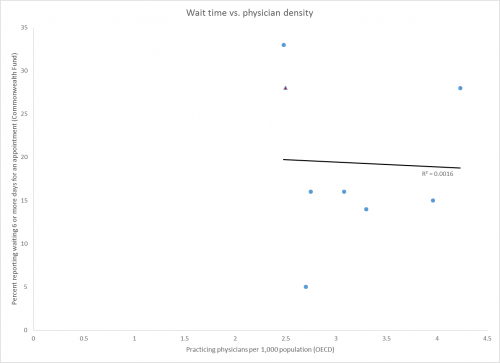

One crude way to estimate how demand and supply are interacting is by looking at wait times — countries with longer wait times might be considered to be in shortage-like situations. Aaron’s covered wait times extensively here. But wait times reflect far more than simply the number of physicians — they reflect how systems are organized, how they’re paid for, what they value (lower costs or shorter wait times?), and even how sick populations are. There’s no correlation between the physician-population ratio and wait times. (R2 = 0.0016 if you can’t read that.)

Let’s bring it back to the IOM report before this gets too long. In their read of the evidence, the IOM report committee believed that the forces of technology and delegation would likely lead to increases in the effective supply of physician services that compensate for the forecast increase in demand. That’s not out of the question — in some simulated scenarios, technology and delegation together can about double productivity. But as noted above, the evidence for technology’s effect on productivity isn’t necessarily replicable, while the evidence for the harms of delegation is disputed. The IOM therefore argued that there was no evidence of a doctor shortage, which of course is not the same of evidence of no doctor shortage. The IOM hasn’t been persuaded that there will be a doctor shortage, but it doesn’t come right out and say that there won’t be one, either.

That brings us to the final point: because these are forecasts, there’s a real possibility they could be wrong. It’s quite possible to consider the data and still worry about a physician shortage simply based on weighted probability. Even if the chances of a doctor shortage are less than 50%, if you think the negative effects and costs of an undersupply are far worse than the negative effects and costs of an oversupply, you might still want to support policies that increase the supply of physicians, especially if those policies might take years to show results. That might be doubly true if you’re a pessimist about technological innovation or think delegation might not spread as much as it could.

Is increasing GME funding the way to increase the physician supply? It’s not as clear-cut as you’d think — but I’ll address that soon enough.