It’s conventional wisdom that people on Medicaid have far worse access to providers than those with private coverage or Medicare. Probably this impression is driven by the many studies that gather data from physicians or their offices on whether and when they will see patients with various types of coverage: Medicaid, uninsured, private, and sometimes Medicare. Studies of this type can give a misleading impression.

It is true that many such studies reveal that physicians are less likely to see new Medicaid patients than those with private coverage or, if they will see them, they offer appointments further in the future. The June 2011 audit study published in NEJM finds exactly this, for example. (Prior TIE coverage of it here and here.) Other studies point this direction as well; see Skaggs et al (2001), Calfee at al (2012), and Lavernia et al (2012), just to name a few.

But the literature is far more nuanced than this. There are studies that find Medicaid enrollees have access on par with that of private patients. In 2011, Aaron wrote about one such study, published in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

The overall acceptance rate of new patients was pretty static from 2005-2008, going from 94.2% to 95.3%. The percentage of physicians accepting new Medicare patients dropped from 95.5% from 92.9% (about 2.5%). But here’s the thing. There was a bigger drop in physician acceptance of patients with private noncapitated insurance from 93.3% to 87.8% (about 5.5%). In fact, they found that over 90% of physicians accepted new Medicare patients.

Schuur et al (2009) found that for callers posing as woman requesting follow-up after abnormal breast cancer screening results, 99% received an appointment within 20 days if they said they had Medicare coverage as compared with 91% if they said they were on Medicaid. This is a difference, to be sure (and it was statistically significant), but it’s not a large difference.

One problem with many of the comparisons between Medicaid and private coverage in the literature is that all private plans are lumped together. If a doctor’s office does not accept new Medicaid patients but does accept a patient from any one of the many possible private plans, then that counts as accepting private patients. The trouble is, no individual is on “any private” plan. Everybody with private coverage is on some specific plan, which has a network. The fairest comparison is between Medicaid and a specific plan. But even studies of this type can be problematic.

Studies that compare Medicaid to a specific plan often they pick one with the most expansive network. This provides a skewed view of Medicaid access since not every privately insured patient is enrolled in the chosen, generous plan. For example, the NEJM audit study mentioned above compares Medicaid to Blue Cross Blue Shield in Cook County, Illinois. As Harold wrote,

This particular study compared Medicaid with Blue Cross Blue Shield, probably the best private coverage in the area. BCBS is pretty costly, in part because it allows broad access to diverse providers. Cheaper private plans offer more limited access through a narrower network of providers.

It would be fairer to compare Medicaid to a “typical” private plan, but I’m not aware of a study that does that.

The final point to make about access studies is that you get a very different impression asking consumers about their access as compared to asking doctors’ offices who they will accept. The latter tends to make access look particularly bad for Medicaid when, according to its enrollees, access might be fine.

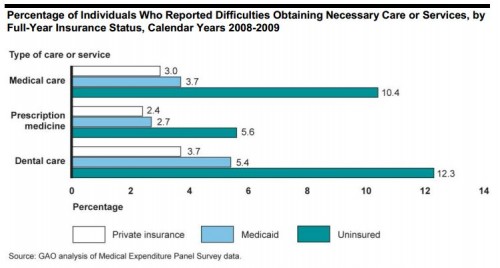

Consider, for example, the 2012 GAO study, about which Aaron blogged. It’s based on the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, a survey of patients, not providers. As you can see from the following chart from the study, apart from dental care (the access to which is a problem for many Medicaid beneficiaries), Medicaid access is quite close to that for the privately insured and lots better than the uninsured. The differences between the percentage of individuals reporting difficulty obtaining necessary care through Medicaid or private coverage for medical care and prescription medicine are not statistically significant.

One gets a similar impression from Mayer et al. (2004), who report “no significant differences in reported unmet need [for specialty care] between children with private insurance and those covered by public forms of insurance,” based on a national survey of children (their parents or guardians, actually).

My point isn’t that Medicaid is a great program with awesome access for all its enrollees. Indeed, neither Medicaid nor providers are monolithic. Medicaid programs vary by state and provider markets are even more local — and they vary by specialty — so it is nearly a certainty that there are some programs in some areas that offer very poor access. But, by the same token, some probably offer quite good access. Additionally, the GAO report cited above documents some key limitations of the program.

My point is that one can get a misleading impression of Medicaid access by relying only on studies that compare it to “any private” coverage and/or on studies that only survey physicians or their offices. Studies show that access can in fact be comparable to that of some private plans, particularly those that consider the direct experience of patients.

It’s worth also mentioning that the literature is more consistent in finding that the uninsured have even worse access than Medicaid or private plan enrollees. Medicaid is less than ideal, but not as bad as many might think; it’s also better than nothing.

This post is based in part on a Medicaid access literature review conducted by TIE research assistant Daniel Liebman. His annotated bibliography is available here.