Chapter 18 of John Goodman’s book Priceless is the final one. It is mercifully short. As I have been throughout, I am assuming you’ve read it and all the other chapters and posts in this series to date. The chapter nicely summarizes the core of John’s proposal for reform of the health care system. I’m going to summarize just part of it and in my own way.

Almost nobody thinks there ought to be no insurance whatsoever. At a minimum, catastrophic coverage is sensible and reasonable. Once it exists, however, the standard operations of supply and demand are distorted. People with third-party coverage for major health shocks are, individually, less motivated to purchase the (sometimes) cheaper preventative and disease-management services that would prevent those major health shocks. If they don’t, there is a negative externality. The (sometimes) higher cost of those major health shocks that are not avoided are borne by the entire risk pool. Premiums go up. The existence of this externality is a market failure.

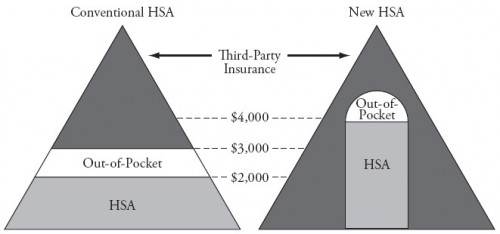

Value-based insurance design is a solution, and John builds it in into his “New HSA.” If health insurers offer some first dollar coverage for at least the subset of preventative and disease-management services that is cost-saving, the externality is avoided. That’s why in John’s “new HSA” there is some third-party payment down to the zero dollar level. However, at zero out-of-pocket price, there is a risk that preventative care will be overused. It’s hard to tune this just right.

John’s solution to this tuning problem is not to try to dictate what’s in the HSA and what should get first-dollar coverage. Instead, he wants to level the playing field of regulations and taxation so that the market can provide whatever products make economic sense in light of cost-benefit trade-offs and consumer demand. After all, this is what markets are for, provided they work well enough.

This invites a new problem, however. No doubt, products more attractive to young, healthy people will differ from those older, sicker ones. In fact, there may be hundreds of different products designed to attract hundreds of different types of people. The products more suited to the costlier people will have higher premiums. Some of those products will fail for this reason. Even though they offer a mix of coverage some people want, if the risk pool they attract is too costly, the products will be unaffordable. This is another market failure.

John recognizes this problem and has a solution, a form of risk adjustment. It’s not terribly different from risk adjustment as we know it, only the risk adjustment payments — how much to transfer from plans covering the healthy pool to the sick pool — is to be set in the market via negotiation between firms. As far as I know, nothing like this has ever been attempted, certainly not on a wide scale and for health insurance products. I would not expect it to go perfectly smoothly in all cases. Some deals will go bad. Some market segments could collapse. To the extent that’s disruptive, it would be a problem, another source of market failure. (In the comments to my review of Chapters 8-9, readers raised some other, related limitations and concerns.)

Also, a necessary condition to make this work is that insurance contracts would have to be longer than one year, as is the current custom. If contracts are too short, people could switch to plans that provide greater coverage for the services they want in the short term and then, after consuming those services, switch to plans that don’t not cover them, saving money both ways. Insurance cannot work on this basis because insurer’s can’t build what they don’t know into their price or even into their negotiated risk adjustment transfers, and individuals are likely to have more information than insurers about their short-term demand.

Of course, long-term contracts hamper competition. The more constraints people have on their ability to vote with their wallets, the less competitive the market. So, a balance must be struck. What’s the optimal insurance duration? I doubt anybody knows.

Still, this is all logical, more so than our current Byzantine patchwork of public and quasi-private insurance programs and products. It is also no less logical than the reasoning behind the ACA that leads from the community rating combined with the banishment of pre-existing condition exclusions to the adverse selection problem to the need for a mandate (or the equivalent) to the need for subsidies. In as much as any of these approaches are logical, they’re also, in different ways, uncertain to succeed and, therefore, come with limitations. Let’s not pretend any approach is perfect in every way. Logic can only take you so far. Not everything about the real world is logical.

So, as is the ACA, John’s approach would be a bold experiment with some risk. Would costs and spending go down? Would quality improve? Would population health measures look more favorable? Would consumers like it? John makes some theoretical arguments and points to some studies. But nothing quite like the totality of his proposals have ever been implemented anywhere in the world. The outcomes are empirical matters and we simply have no evidence. In the face of uncertainty, caution and incrementalism are reasonable. They are certainly politically rational, which cannot be discounted.

There is one thing the market absolutely cannot do, though. It cannot tell us how much public support we should provide for the poor, elderly, and very sick, the populations relying on Medicaid, Medicare, and in 2014, some subset of those relying on exchange subsidies. Minimum levels of support — even in dollar terms — need to be defined. We, collectively, need to decide the “right” level, even though we can’t know it. The question, How much income redistribution is right? does not have a market-based solution.

The foregoing, plus some things I wrote in other posts about the book (in particular in my reviews of Chapters 9 and 10), describes ways John has moved my thinking. The logic of his view (just described) was not evident to me before reading the book. But, boy did I have to work hard to receive his insight! I think John does his good ideas a disservice by dragging the reader through what is, in my view, a parade of self-contradictions, overreaches, unnecessary fights, and misleading impressions. Pulling from my prior posts, below are just a few examples. In some cases John has explained a bit more in comments to my posts, but that doesn’t change the impression I received from the book, which is what my posts are about. They are:

- John thinks we shouldn’t try to replicate good models of health care delivery, except in cases where we should.

- John did not tell readers that access to physicians didn’t change upon implementation of Romneycare in Massachusetts even though he mentioned a study that shows just that.

- John seems to object to the use of science and guidelines in the practice of medicine except when it’s OK.

- John tries and fails to upend the conventional wisdom that the US spends far more on health care than other nations and achieves mediocre health outcomes.

- John takes on Medicare spending growth and administrative costs, making mistakes on both.

- John believes non-price barriers are far more germane to access to health care than price-barriers. I pointed to evidence that shows they’re about equally germane. It ought to be sufficient to acknowledge both are important. John doesn’t.

- John missed one important result from the RAND health insurance experiment.

- Don’t even get me started on Medicaid. It’s better for the health of the population it serves than John would have you believe. This, perhaps, serves as John’s justification for proposing to cut Medicaid by more than half.

- John is misinformed about ACOs.

Some of these problems arise when John tries to buck conventional wisdom. But it is not necessary to do that for him to make his key points. (Go back to the top of this post and see how I made some of his points without reliance on any of this.) It’s just gratuitous contrarianism, an unnecessary fight. It only distorts and distracts. To the extent I find his arguments in opposition to a complete view of the evidence, it is not credibility enhancing. Notice that despite differing with him on these ancillary issues, I find value in his core points.

Beyond my reaction to what was in the book, I also took note of some things that were left out. I was disappointed that health literacy and the cognitive limitations of Medicare beneficiaries did not receive any attention. The book is devoid of any consideration of the health value as opposed to consumer value of the care we receive. Do we just trust that providers are selling things of value? Why?

Given the reality that John’s full proposals are unlikely to be implemented in the form he suggests, what does a partial and politically-constrained version look like? How does it operate under the bureaucracy we actually have, not the idealized one we might imagine? What could be the unintended consequences? These are challenging questions, and I don’t expect John to have answers. But I’d like to see them acknowledged as valid ones. That they are is the very reason the status quo is hard to change.

In this or in any of my other posts in the series, I hope I have not come off as too hard on John. I meant none of it personally. It’s always about the ideas and the evidence to me. I need the former to be consistent with the latter much more than I need to “win” anything. I tend not to trust people who have not convinced me they feel the same. Why should I?