Premiums always seem to go up, a lot. Yet, I’m not convinced they should be doing so right now, not unless the current recovery from a recession is different from past recoveries. I’m not the only one questioning big premium hikes. Robert Pear reminds us that the Affordable Care Act includes provisions that will lead to greater scrutiny of health insurance premium increases.

In some states like New Hampshire, groups of more than 20 workers have experienced premium increases of around 20 percent this year, while smaller groups have seen increases of 40 percent or more. At the same time, insurance agents say, coverage is shrinking as deductibles have increased and insurers limit the choice of hospitals.

To ensure that “consumers get value for their dollars,” the new health care law required annual reviews of “unreasonable increases in premiums.”

Under the new rule, federal and state officials will review rates in the individual and small-group insurance markets. In effect, the administration said, large employers can take care of themselves, as they are more sophisticated purchasers and have more leverage in negotiating with insurers.

Perhaps large employers don’t need government assistance to obtain better deals. Maybe their market power cancels that of large insurers, returning the market to something like a competitive one. Jared Bernstein explained that insurers are claiming that premiums must rise to protect against future higher claims due to demand for care that was unmet during the recession. However, this shouldn’t happen in a competitive market, he writes.

In competitive markets, sellers can’t typically set today’s prices based on where they expect demand to be in the future. If one of them did so, others would capture their market share by pricing based on current supply and demand conditions.

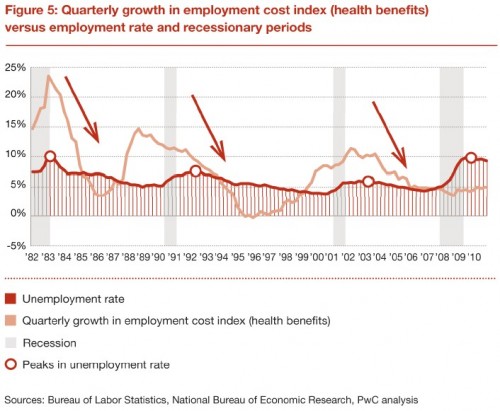

Actually, it probably shouldn’t be happening even if the market is not that competitive, at least not according to recent history. As the following chart from PriceWaterhouseCoopers shows, in the years following unemployment peaks, the rate of increase in employers’ costs of health benefits fell and fell dramatically.

If employers’ health care costs rise more slowly after peak unemployment, so should premiums. Are we not in a period following peak unemployment? Should group-market premiums be increasing rapidly now? Not according to recent history.

Why might health care costs rise more slowly after peak unemployment? I don’t really know, but I can speculate. Here are some possibilities that come to mind:

- Relatively sicker individuals disproportionately leave or are forced from the workforce during periods of high unemployment. If you’re sick and possibly can’t work as hard, maybe you’re more likely to leave or be laid off, and you may never come back even when the economy begins to improve.

- Similarly, firms preferentially hire healthier (or younger) individuals as the economy improves. Younger workers are cheaper to hire, so this is also an incentive.

- Concerned about retaining their jobs, people take less time to visit the doctor or are less likely to take sick or disability leave. If your colleagues had just been laid off, wouldn’t you work extra hard to keep your job, possibly forgoing care?

- Periods of rising unemployment are bad for health. (Actually, I’ve seen just the opposite reported, so I’m not sure I buy this one.)

- Worried about losing one’s job, and health benefits, in a time of rising unemployment, people use more care while they have insurance. So, it isn’t that health costs fail to rise as fast after peak unemployment so much as the rate of increase is boosted as unemployment grows. The peaks are high, the troughs aren’t low.

What am I missing?

UPDATE: Colleague and occasional contributor here, Steve Pizer, suggested to me that employers may preferentially hire low-wage workers after a recession. Those workers may be less likely to be offered or to take up insurance. That makes employer health costs lower if averaged over all employees, and it wouldn’t necessarily translate into lower premiums for those who do take up insurance. See also this prior post on low wage workers and health insurance.

UPDATE 2: Read the comments for other good suggestions from readers. More on the underwriting cycle (with graphs!) here, here (to which there was a follow-up here).