In a previous post, I walked you through my decision to have radiation therapy only, without chemotherapy. Now I’ve started therapy. This post is about what it’s like. I hope it will help you make an informed decision about radiation if, God forbid, you get throat cancer. Or it can give you insight into the experience of someone in your life who is going through this.

Radiation therapy means that a machine projects a beam of particles at your tumour. The particles damage the DNA in the tumour cells, making them less able to reproduce, and killing them. But to hit the tumour, they need to pass through healthy tissue, and they can also hit the healthy tissue on the margins of the tumour. Radiation damages healthy tissue, but not as much as tumour cells. The particles are photons, so if you think this sounds like getting a severe sunburn, that’s not far off. If all goes well, the radiation will destroy my tumour and merely badly burn the throat tissue surrounding it.

There are other side effects. Bones exposed to radiation are weakened. Radiating the throat damages your salivary glands, giving you a dry mouth. This is unpleasant, but what’s worse is that saliva is essential to tooth decay prevention. A dentist who specializes in radiotherapy patients delivered a come-to-Jesus talk. I have to give my teeth a special fluoride treatment every day, or I will need horrifying dental surgery. Yes, Lord! I haven’t missed a treatment yet.

Proton beam therapy is also used in the US. There are data indicating that proton beams are just as effective as photons in terms of throat cancer survival, but protons produce less severe side effects. However, proton beam therapy is not available in Canada for my cancer. This is because

Proton therapy costs range from about $30,000 to $120,000 [US dollars]. In contrast,… IMRT (intensity-modulated radiation therapy [which is what I am getting]) costs about $15,000. A radiation treatment center with stereotactic capabilities costs about $7 million to build, versus roughly $200 million for a proton therapy center.

This price difference is one reason why Canada spends $4800 and the US $9900 per capita on health care (2016 spending). This difference allows Canada to spend substantially more on other social benefits, including universal parental leaves, child care, and subsidized university tuition. My view is that this is a better set of investments in public health and well-being, even though I am the loser in this case.

Before I started treatment, I got a computerized tomography (CT) scan of my throat to precisely locate my tumour. They began by injecting a radioactive dye that the tumour would preferentially absorb. This made the tumour stand out in the CT image. The purpose of getting a precise image is to allow the radiation team to accurately target the beam at the tumour and minimize the exposure of healthy tissue to radiation.

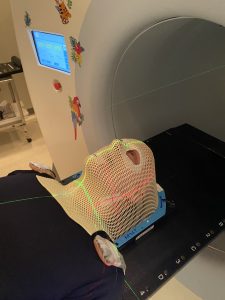

At the CT session, the radiation team made a mask of my face, head, and neck. First, they took a big sheet of plastic mesh and warmed it until it softened. Next, I had to lie on my back on a table with my head on a moulded plastic cushion that positioned my head to look at the ceiling. This is the position that they want my head to be in during the radiation. Then they placed the softened plastic sheet over my head and pressed it down so that it conformed to my head and neck. It’s a mesh, so I could breathe through it. In a couple of minutes, the plastic cooled and became rigid. They lifted it off — it wasn’t sticky — and there was my mask.

Why in the world would they do this? I wear the mask during each radiation session. It keeps my head in exactly the same position throughout each session. If I moved my head, the precise targeting of the radiation beam would be for nought. The beam would hit my tumour less and my healthy tissue. more

I will be getting 35 radiation sessions on a Monday through Friday schedule. The idea is to limit the radiation dose at any given session while letting the tumour-killing exposure accumulate slowly. But, of course, this means that the side effects accumulate too. So far, I have had ten sessions.

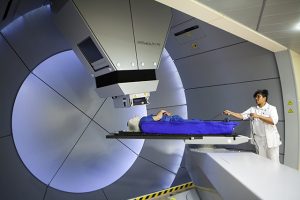

Here’s what happens in a session. I lie down on the table of what looks like a CT or MRI scanner. There’s a bit of work to get me correctly positioned with respect to the laser lines you can see in the photo. Then they place the mask over my face and clamp it down to the table. This holds my head in position. Then the table, which is motorized, slides me so that my masked head enters the machine. There’s a lot of noise that must be connected somehow to the generation of the beam. After five minutes or so, the table slides me back out. There’s more noise, which I gather is the machine reconfiguring the beam in some way. Then the table slides me back into the machine for another few minutes of radiation. Then I’m slid out, they unclamp the mask, and I’m done.

What is it like to be in the machine? I can feel the warmth of the radiation. It’s not painful — at least, not yet — but there’s an increasingly urgent message from my flesh: “You do realize that this is burning me?” This is clearly going to get worse as treatment progresses.

At first, the mask was a challenge. I can breathe through it, but my breathing is somewhat restricted. The lower edge of the mask presses a bit against my throat. There’s no real danger. But we humans are extraordinarily sensitive to anything that constricts our airways. During my first radiation session, I couldn’t help but think, “what would happen if I started to have trouble breathing?” “What would happen if this thing pressing on my throat got a little tighter?” Having those very thoughts made my heart beat faster, and that made me breathe a little more quickly. But trying to breathe more quickly just increased the feeling that I didn’t have free access to air. That raised my anxiety, which made my heart beat yet faster, and… you can see where this was going.

Deo gratias, I am not an anxious person. And I have participated in sports — long-distance open-water swimming and scuba diving — that teach you to remain calm under stress through careful control of your breathing. I’ve also logged 10 gazillion hours of Buddhist meditation, watching my breath and experiencing how simply breathing shapes your experience of your body and the world. So I knew exactly how to manage being masked: long, slow, steady breaths.

Breathing in, I calm my body and mind.

Breathing out, I smile.

Dwelling in the present moment, I know this is the only moment.

– Thich Nhat Hanh, Buddhist monk

As you can imagine, the mask makes radiation therapy exceptionally difficult for anyone with claustrophobia, anxiety disorders, or panic disorder. Some folks need to be anesthetized. Hypnosis and cognitive behaviour therapy have also been used to train people to tolerate it. If it hasn’t been tried already, may I suggest that a brief course on meditating on the breath might greatly help radiotherapy patients?