In case there is any doubt, a new study using experimental methods shows that how physicians get paid and by how much does affect patient care, but it is not the only factor. The health of patients matter too. I find this relatively unsurprising. Yet I think the work is worthy of note because not everyone may think as I do. Plus, the methodology is interesting and leads to very clean, clear results.

The paper, by Heike Hennig-Schmidt, Reinhard Selten, and Daniel Wiesen, appeared in the Journal of Health Economics and is titled How payment systems affect physicians’ provision behaviour—An experimental investigation. As the title states, this was an experiment, not an observational study.

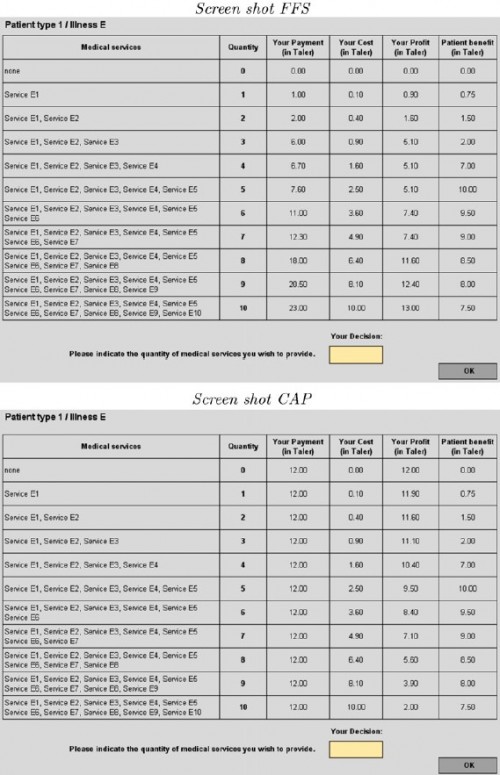

In a controlled setting, the researchers asked medical students to choose the quantity of medical care to provide to hypothetical patients enrolled in either fee-for-service (FFS) or capitated insurance plans. Under the former, physicians are paid for each additional unit of care. Under the latter, they receive a lump-sum payment independent of units of care provided. In the experiment, quantity of care is an amount indexed by the integers 0 (no services) to 10 (the most services). In advance of making the quantity selection, the physician has full information about how the quantity selected will affect payment, costs, and profit (or income) and how it will benefit the patient. Here’s how it looks in the experimental setting (click to enlarge):

As shown in the figure above, revenue varies by quantity for patients assigned to FFS type payment but not for patients assigned to capitated CAP type payment. What’s shown above are the payment, cost, profit, and patient benefit schedules for patient type 1 with illness type “E”. There are other types and other illnesses though, with different schedules. Patients vary by illness (there are five, labeled “A”, “B”, “C”, “D”, “E”) and by three levels of need for services (level 1 needs 5 units of service for optimal health, level 2 needs only 3 units, and level 3 needs 7 units). I know this is a lot of detail, but it is necessary to understand the results, which is where it gets interesting.

Oh, before I get to the results, one more cool thing about the experiment. The physician (student) participants actually earn the money they generate from treatments prescribed in the experiment. Since there are no actual patients, the researchers included an incentive for the physicians to take patient concerns seriously by converting patient benefits into contributions to a charity that cares for real patients. Given the constraints of experimenting on actual people, I think this is a very cool design. Still, one might wonder how things might be different in the presence of real, flesh and blood patients.

OK, about the findings:

- Payment systems matter. More services are provided under FFS than CAP. On average, patients receive more services than are optimal under the former and fewer than optimal under the latter.

- Patient health matters. That is, physicians do respond to how much treatment benefits patients. Still, under FFS, patients in good and intermediate health are overserved. Under CAP, patients in poor and intermediate health are underserved.

- Payment systems affect health (or patient benefit). Patients in good and intermediate health suffer losses under FFS due to overprovision. Patients in intermediate and poor health suffer losses under CAP due to underprovision.

It should be perfectly clear from these results why patients in the real world might self-sort according to health, even aspects of health that are unobservable to the researcher. A patient in poor health attempting to optimize his benefit would do better under FFS. A patient in good health gets better results under CAP.

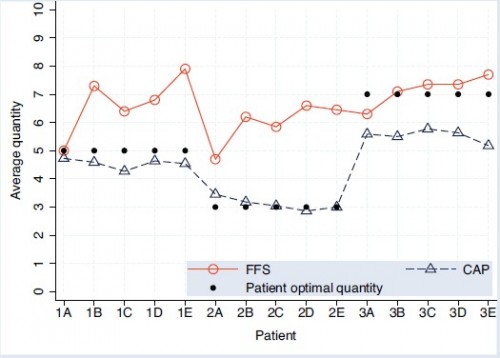

Even though I already stated the results, the following chart conveys them so beautifully you really must take a look. (Come on, you’ve made it this far!)

Remember, A-E are the (abstract) illness types and 1-3 index how much medical care would be optimal. The solid, black dots show the optimal level of care. Patients of type 1 (1A, 1B, etc.) would do best with 5 units of care, etc. Notice that under both payment systems, actual quantity provided is correlated with what would be optimal, highest for type 3 patients, lowest for type 2. So, patient needs matter. Still, patients needs don’t tell the whole story. Provision of care under both payment types differs from optimality, most strongly for types 1 and 2 under FFS and type 3 under CAP. Finally, CAP levels of care are systematically lower than under FFS.

Conclusion: money matters, though so do patients. Lesson: your doctors, or medical providers generally, are not just taking care of you. They’re taking care of business (themselves) too. Don’t even try to convince me you’d behave (qualitatively) differently in their shoes either. We all like to get paid! Keep in mind, though, your doctors probably don’t know the exact optimal level of care you need, as those in this experiment did. That probably makes it more likely their decisions will be influenced by other factors, including financial. On the other hand, in the presence of an actual patient, maybe they make different choices.

Still, I believe this study reveals a fundamental truth: money matters (more evidence here).