The mental health care received by US children has changed dramatically in the last two decades. The bottom line is that US mental health care for kids is primarily about using drugs to treat boys with disruptive behavior disorders (ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder). This raises many questions.

The mental health care received by US children has changed dramatically in the last two decades. The bottom line is that US mental health care for kids is primarily about using drugs to treat boys with disruptive behavior disorders (ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder). This raises many questions.

Let me first walk you through the data from a fine article in the current JAMA Psychiatry by Mark Olfson, Carlos Blanco, Shuai Wang, Gonzalo Laje, and Christoph Correll. Olfson and his colleagues gathered records of outpatient visits to physicians’ offices from the 1995-2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (N = 446,542). The study describes changes in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults in office-based medical practice. The terms “office-based” and “medical” are important, because mental health care is delivered in many settings, including hospitals, residential facilities, and juvenile justice detention centres. Moreover, many professionals other than physicians deliver mental health care to children, including psychologists and social workers. So the data here concern only a portion of the country’s mental health care.

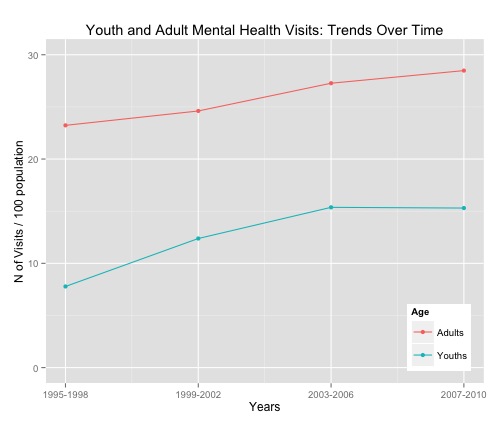

The first point is that there has been substantial growth in mental health visits for children and adolescents (97% growth from 1996-1998 to 2007-2010), compared to 23% growth for adults.

What is graphed here is the number of visits / 100 children in the population / year. The number of unique children being seen / year will be smaller. The number of children being treated by physicians is nevertheless appreciable, and Olfson et al. comment that

the growth in the volume of office-based mental health visits by young people suggests that progress has been made in reducing the large number of young people with untreated psychiatric disorders.

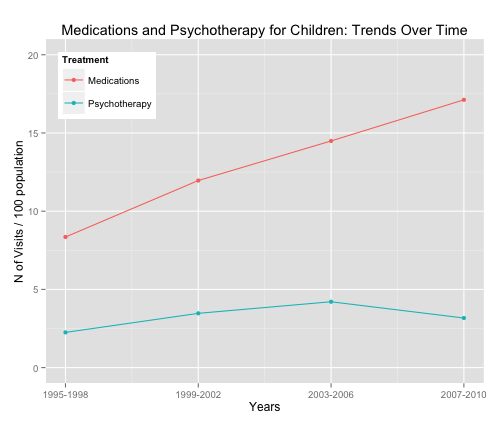

The next question is, what care do kids get when they have a mental health visit?

The number of medication visits / 100 children has grown 105% since the late ’90s and it continues to grow even though the number of visits to physicians has plateaued. Psychotherapeutic visits to doctors have not grown, but keep in mind that kids also see psychologists, social workers, and other mental health professionals who are more likely to deliver psychotherapeutic care.

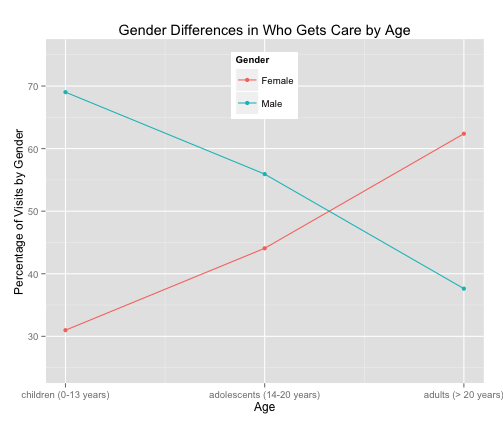

Now let’s look at who is being treated at each age.

The gender distribution of mental health care flips with age. In childhood, mental health care is primarily for boys. Girls start showing up in larger numbers around puberty and office-visit-based adult mental health care is predominantly for women.

To understand this dramatic shift, we need to look at what problems are getting treatment as a function of age.

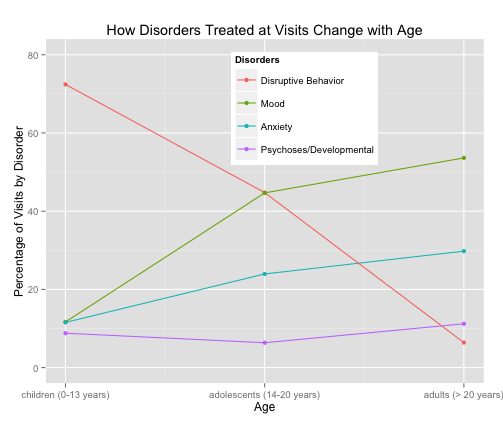

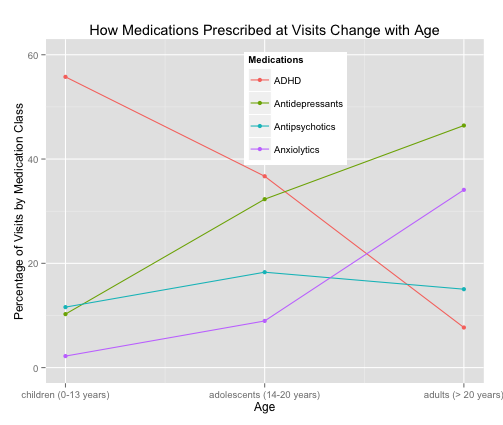

(Note that the percentages do not add to 100% because I have not presented all the categories of disorders and because some visits are associated with multiple disorders.) Mental health care for children is about disruptive behaviour disorders, but these diagnoses nearly disappear among adults. Instead, office-based care for adolescents and adults is primarily about mood disorders (depression and bipolar disorder) and anxiety. What happens with medications is closely related:

Stimulant medications for ADHD dominate childhood prescribing and nearly vanish by adulthood. Antipsychotics have seen a nearly ten-fold increase since the late ’90s.

In summary, since the late ’90s there has been a massive shift toward the use of medications in office-based mental health care for American kids. Much of this is prescriptions of ADHD medications and antipsychotics for conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorders, mostly for boys. (There are girls with disruptive behaviour disorders, but they are less common.) I think this raises at least four large questions.

1. Where are the girls in childhood mental health care?

If women are the primary consumers of office-based mental health care in adulthood, are we missing an opportunity to prevent mood and anxiety disorders in childhood? Perhaps the answer is no. It could be that the onset of these disorders is tied to puberty. In addition, a lot of stressful social expectations for young women kick in during the early teens. If so, it may be impossible to identify which girls are at risk for adult mental health problems until the girls become adolescents. But I can’t help but worry that we are missing opportunities for prevention.

2. Why the increase in the number of prescriptions to children for disruptive behaviour disorders?

Olfson and his colleagues suggest that

During the study period, individuals in the United States became more willing to take psychotropic medications for different conditions, including relatively minor concerns such as coping with the stresses of life. The US FDA Modernization Act (1997) encouraged pharmaceutical manufacturers to study their approved drugs in pediatric populations by extending existing marketing protections for an additional 6 months. The decreasing stigma associated with seeking treatment for mental health problems, which has been especially pronounced among younger individuals, may have further contributed to the increasing number of prescriptions of psychotropic medications to young people. [Finally,] …the development of disease management and other insurance- and employer-driven mental health quality-of-care efforts for depression and other mental disorders may have contributed to the increase in the number of psychotropic and mental disorder visits during this period.

That is: Americans now think that mental health problems are primarily addressed through medication and pharmaceutical companies have encouraged this. Pharma handed doctors a hammer — medications — and the doctors started to see nails — disruptive behaviour disorders — that needed to be hammered down.

This is plausible, but we need to know more about the increase in disruptive behaviour disorders. Have the drug companies encouraged doctors, teachers, and parents to mislabel male immaturity as pathology? Or has society changed in ways that require boys to be civilized and cooperative at younger ages? (I raised four boys. If there is a next life, I think I will foster bear cubs instead.) Or have we as a society become less effective in socializing young boys? For example, there are now more families headed by single working women. Are these families less effective at socializing boys?

3. What happens to the boys with disruptive behaviour disorders when they grow up?

Lots of boys are seen for mental health care as kids, but not when they are older. What happens to them? In some cases, these boys are no longer seen because the problem goes away: either because the treatment works or the boy matures. But others do poorly. Sometimes, the boy grows up and the parents stop bringing him in for care (people with disruptive behaviour disorders do not bring themselves in for care). Some of the disruptive boys become increasingly antisocial and progress to delinquency and crime. And thus some of the boys treated as for disruptive behaviour disorders as kids become adult men in prison. These boys — I wish we had a reliable count — need to be viewed as cases where treatment failed.

4. We have greatly increased the mental health care that US children receive — has it done any good?

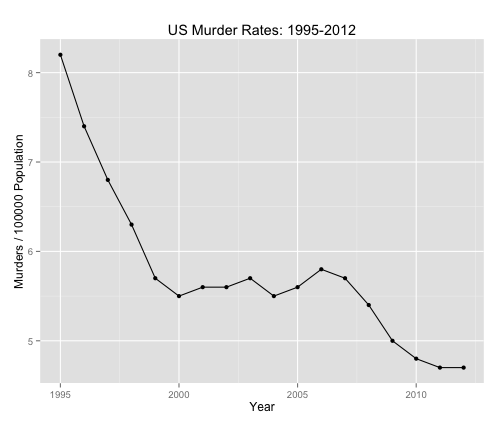

At this point, an appreciable proportion of the children who have mental health disorders are actually receiving treatment. Have we seen an improvement in the population mental health of young people? I’ve asked this question to child mental health professionals and it usually elicits eyerolls — it seems obvious to them that, if anything, kids are doing worse. But is this so clear? Consider that the period of greatly increased use of medications for disruptive behaviour disorders has also seen a profound decrease in violent crime.

Of course, there are many other factors driving this decline. But murder is primarily a young man’s crime, so it’s at least possible that increased mental health care for kids is part of the fall in violent crime.

Speculation aside, it is impossible to say whether US kids have benefited from increased mental health. The primary reason is that the US has no way to reliably measure the mental health of children on a population basis. This is in itself a scandal.

For more on this, see previous TIE posts on ADHD here, here, here, here, and here.