Levy and Meltzer’s update of their 2004 book chapter on the effect of health insurance on health is not new. It was published in 2008, but I’ve never blogged on it. It’s a great and concise resource. Here’s an ungated PDF.

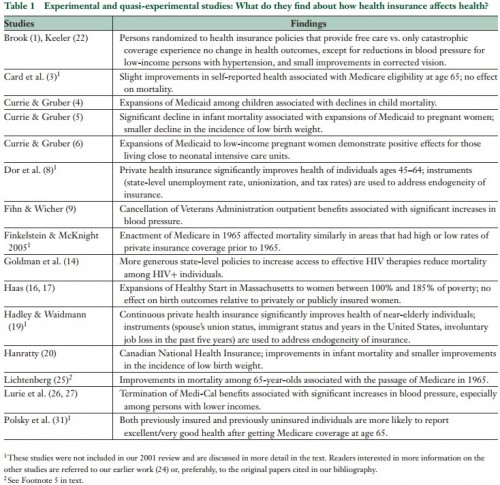

Their Table 1, below, rounds up the best evidence available at the time of publication (click to enlarge).

Most, but not all, of these studies find that expansions of health insurance result in health improvements. The fact that only some of these studies find an effect on health illustrates one important limitation of this type of study: The results of natural experiments may be specific to the population studied. As a result, different natural experiments may yield different conclusions. For example, Card et al. (3) show that the transition onto Medicare at age 65 does not reduce mortality at that age, but Currie & Gruber (4, 5) show that Medicaid expansions reduced child and infant mortality. These varying results are not necessarily contradictory, however, because they apply to different populations. But these differences underscore the fact that the question “How does health insurance affect health?” is complicated, and the answer will depend on (among other things) what we mean by health insurance and whose health is being considered.

Does health insurance improve people’s health? You’ll find Levy and Meltzer cited by both those who answer “yes” and “no” to this question. Of course, as they plainly write, the real answer is nuanced. It depends on which type of people you examine and what you mean by “health.” Just mortality and all Medicare beneficiaries, no discernible effect. Other physical health outcomes and/or other (perhaps sicker) populations, the effect is apparent.

Are those benefits worth the expense? That’s a completely different question and a subjective one. Your answer to it cannot change the objective facts about whether insurance improves health.