A long post on important topics: Medicare hospital payments, private hospital prices, hospital costs, and market power.

In the third chapter of its 2011 Report to Congress (pdf) MedPAC reports that “profit margins on Medicare patients remain negative for 64 percent of hospitals.” That sounds dire, and maybe it is. However, it does not itself mean that Medicare payments are too low.

To say that Medicare payments are “too low” begs the question, relative to what? Typically what one means by this is that Medicare pays hospitals at rates lower than private insurers. That’s true, in general. But who is to say that private insurance rates are not too high? MedPAC, I, and others have argued that they, in fact, are, in many cases.

Often we presume that market-based prices are “correct” or closer to correct than government set ones. In markets that are sufficiently competitive prices are “correct” in the sense that they lead to an economically efficient allocation of scarce resources. Without unpacking what the means precisely, suffice it to say that an economist can claim a degree of “correctness” to prices in a competitive market.

Even if you buy the economist’s logic however (and maybe you don’t), notice the assumption required: competitive markets. Are hospital markets competitive? Some are. Many are not. Lots of evidence to support that statement has been posted on this blog.

Most recently, I summarized the work of Glenn Melnick, Yu-Chu Shen, and Vivian Wu as published in their recent Health Affairs paper “The Increased Concentration Of Health Plan Markets Can Benefit Consumers Through Lower Hospital Prices.” One of their findings was that “[Sixty-four] percent of hospitals operate in markets where health plans are not very concentrated.” Another was that “[I]n most markets, hospital market concentration exceeds health plan concentration.” And finally, “[G]reater hospital market concentration leads to higher hospital prices.”

Go back and read the first paragraph of this post: 64 percent of hospitals have negative Medicare margins. And, as just quoted, 64 percent of hospitals operate in markets where health plans are not very concentrated. That the two numbers match exactly is surely coincidence. There are many ways to define hospital markets and likely the sets of hospitals with negative Medicare margins is not precisely the same set that operate in markets where health plans are not very concentrated. Nevertheless, there is a connection.

An unconcentrated health plan market is one in which hospitals have greater ability to raise the prices health plans pay. The more health plans, the better hospitals can play one off another. Hospitals are not reliant on a dominant plan for a flow of patients. They can afford to be excluded from some plans’ networks. Thus, prices can be profitably increased. All other things being equal, a market with low health plan concentration is one in which hospitals have relatively greater market power, the ability to negotiate higher prices and earn higher profit.

MedPAC spells out the consequences their report. They examined financial performance of hospitals in 2009, stratified by hospital market power. They didn’t phrase it that way, but that’s what they did. The way they put it is that they defined groups of hospitals in terms of degree of “financial pressure.” Hospitals under high financial pressure had very low profits from non-Medicare payers in the five years preceding 2009 (on average, below one percent) and whose net worth would have grown at an annual rate of less than one percent based on non-Medicare payers alone. Hospitals under low financial pressure had high non-Medicare profits (above five percent on average) and non-Medicare net worth growth above one percent annually in the prior five years. All hospitals not under high or low financial pressure were said to be under medium financial pressure.

The “low financial pressure” hospital group has relatively high market power by definition. It earns non-Medicare profits above five percent, on average. The “high financial pressure” group is not able to exercise market power to as great an extent, earning less than one percent profits, on average.

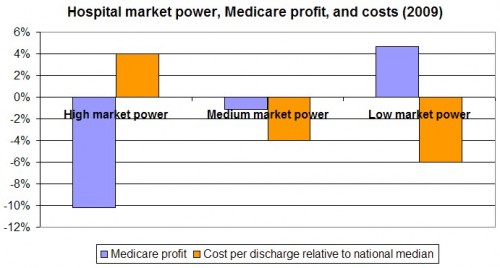

So, after grouping hospitals by their degree of market power, what did MedPAC find? It found that hospitals with high market power (low financial pressure) had negative Medicare profits and that hospitals with low market power (high financial pressure) had positive Medicare profits. Hospitals with medium market power (medium financial pressure) had a degree of Medicare profit between the other two groups.

This makes sense when you think about costs. How would you expect costs to vary by market power? Well, hospitals able to charge higher prices (those with high market power or under low financial pressure) have considerable head room to incur higher costs. They certainly have relatively lower incentives to keep costs down. Not so hospitals with low market power (under high financial pressure). Their costs ought to be lower because they can’t afford to be otherwise. That’s what MedPAC found.

Below are their numbers in a chart, based on data from Table 3-5 of MedPAC’s report. The high market power group of hospitals lose more than 10 percent on Medicare patients (-10.2 percent Medicare profit). It has cost per discharge 4 percent above the national median. The low market power group of hospitals earn more than 4 percent on Medicare patients (4.7 percent Medicare profit) and has a cost per discharge 6 percent below the national median.

In light of this, let’s return to the question of whether the fact that 64 percent of hospitals have negative Medicare profits means that Medicare payments are too low. MedPAC’s answer is, “No.” Their interpretation of the data is that hospitals invite their own negative Medicare profits by having higher costs, which is somewhat within their control. Perhaps in part due to their higher costs (e.g., if they’re providing high-priced amenities that are attractive to patients), hospitals with relatively low or negative Medicare profits have high market power and, therefore, high non-Medicare profits. It’s not that Medicare’s payments are too low, it’s that the prices charged to non-Medicare payers are too high, as are hospital costs.

And, we really can say those private prices are too high in a precise sense. Market power is due to lack of competition, which is one form of market failure. In the presence of such failures, the prices charged are not economically efficient. Not only do they lead to higher private premiums, they put pressure on Medicare to keep its prices higher than they would otherwise be. Market power has spillover effects, leading not just to higher prices in the hospital market, but higher taxes (or debt) to pay Medicare’s bills.