We’ve discussed the RAND health insurance experiment a number of times on the blog. In a nutshell, that was the randomized controlled trial that showed that cost-sharing, or making people pay for some of their care, led to them using less care. the caveat to this study,was that people didn’t discriminate between necessary and unnecessary care, making some of us skeptical about the wisdom of indiscriminate increased cost-sharing.

This month, in Health Affairs, is a study that builds upon this work. It’s very much worth your time.

At the Mayo Clinic, before 2004, you had one of three choices for a health benefit. One cost a lot, but had no cost-sharing at all. Another cost a middle amount, had no deductible, but some co-payments at the time of care. A final plan was the cheapest, and had a more significant deductible (but no co-payments).

In 2004, these plans were scrapped and two new plans were introduced. Both completely eliminated any cost-sharing for primary care and preventive services. Both had co-payments for specialty care and for ED visits. One of them cost more, and had no deductible; the other cost less and had a deductible. Both also introduced co-insurance, meaning that people had to pay a percentage of all other care, including diagnostic testing, imaging, procedures, and hospitalizations.

This means that a natural experiment could be run. Although this was not a randomized controlled trial, because of the changes, a number of groups could be compared, and a number of hypotheses could be tested. These included the following:

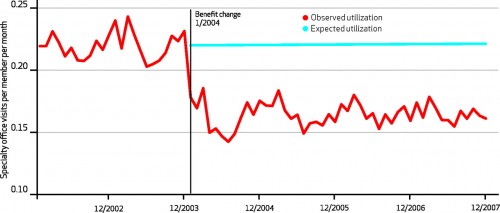

- Would utilization go down with an increase in cost-sharing for specialty care?

- Would diagnostic testing go down with an increase in cost-sharing?

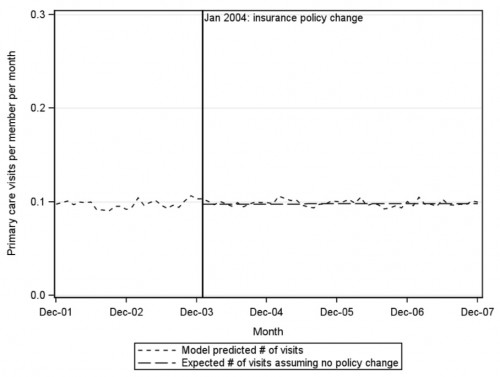

- Would primary care utilization go up with a decrease in cost sharing?

Let’s look at the first question:

The introduction of a $25 co-pay and 10% co-insurance seems to have had a significant impact on the utilization of specialty services. Not only that, but the impact seems to have been steady for years. Impressive, but not unexpected, given the results of the RAND HIE.

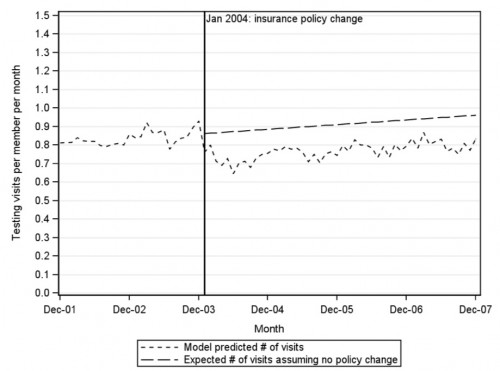

What about the second question?

Well, imaging dropped off with the introduction of 10% co-insurance, but then started to creep back up. The authors think that imaging may increase over time naturally, and that the change dropped the line down on the Y-axis, but perhaps didn’t change the overall slope.

But what about the third question. Did dropping cost sharing increase the use of primary care?

Huh. Dropping the co-pay from $10 to $0 for primary care visits appears to have had no effect on getting people to increase their use of primary care.

Now first, some caveats. My concerns about hypothesis #1 and #2 are that we don’t have a lot of actual outcomes to go along with these. Decreased use of services is fine as long as it doesn’t result in bad health outcomes. We do know that people got less testing and went to fewer specialty visits, which did save money. But we don’t know if people fared worse, better, or the same when they went without that care.

But it’s hypothesis #3 that really has me thinking. One of the ways the ACA is supposed to make things better is by dropping all the cost-sharing for primary care and preventive services. This is meant to increrase utilization of those things, which would improve outcomes, and (some claim) reduce costs. But this study showed that dropping that cost-sharing did nothing to increase utilization.

In other words, cost-sharing may be useful, when increased, to reduce utilization. It may not be as useful, however, when decreased, to increase utilization.

As Sarah Kliff puts it (stealing one of my favorite metaphors), cost-sharing may be a good stick, but it’s not a good carrot. We need to find better ways to induce people to use the services we want them to use.