If Congress takes no action, Medicare payments to physicians will be slashed by 27.4% on January 1. If this sounds familiar, it is. Roughly annually, if not more frequently, Medicare is on the brink of making huge cuts to physician payments. The reason is that, through a complicated means, the “Sustainable Growth Rate” (SGR) formula put in place in 1997 requires per beneficiary payments to grow no faster than per capita GDP. Every time Congress permits them to exceed economic growth — which it does nearly every year — the amount by which they’d have to be cut the following year to return to the SGR-dictated trend grows larger.

Hence the annual search for a “doc fix,” a way to, once and for all, rid ourselves of the SGR formula that we almost never obey anyway. With less than two months to go before the next “doc fix” deadline, the recent Health Affairs/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation policy brief that reviews the problem and several proposed solution was well timed. I refer you to it for more background on the SGR, Medicare physician payments, and contemporary context. Below is a summary of two of the proposed solutions it offers.

MedPAC has proposed to replace the SGR with legislatively set payment rates as follows.

Rates for patient visits to primary care physicians would be frozen at their current level through 2021. Payments for other services by those physicians, and for all services by non–primary care specialists, would be reduced by 5.9 percent in each of the three years 2012–2014 and then be frozen through 2021.

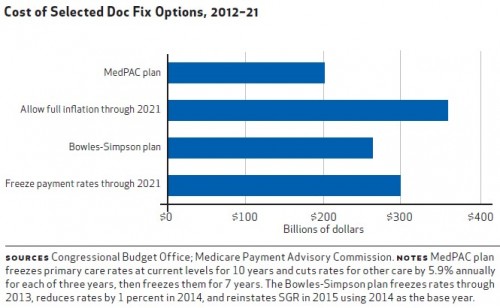

The price tag for this approach is $200 billion over 10 years, as shown in the figure above. I’m not clear on what happens after 10 years. One guess is that the SGR would kick back in 2021 (someone please correct me if I am wrong on this). The reason primary care is treated preferentially by MedPAC is to encourage greater access for such services. MedPAC suggests several potential offsets to their $200 billion plan, including cuts to drug manufacturers, skilled nursing facilities, clinical labs, and a tax on Medicare supplemental plans (Medigap). Needless to say, there are a few political obstacles.

The Bowles-Simpson Commission has offered a different proposal.

[It] would freeze physician payment rates through 2013, reduce rates by 1 percent in 2014, and then reinstate the SGR system in 2015 using 2014 spending as the base year. In effect, past overspending would be forgiven, offering physicians a new chance to restrain spending but threatening them with future penalties for failing to do so. The estimated 10-year cost of this approach is $261.7 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Not only does Bowles-Simpson return to the SGR relatively soon (2015), its approach costs more than the MedPAC one. However, note from the figure above that neither Bowles-Simpson nor MedPAC are as costly as either a 10-year payment rate freeze ($300 billion over 10 years) or allowing rates to track inflation in the cost of running a physician practice ($358 billion over 10 years).

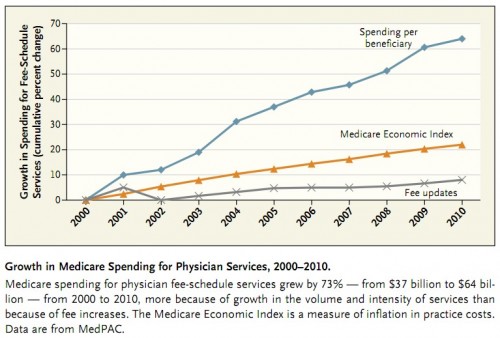

In fact, what is likely to happen if there is no long-term doc fix is neither of those. Congress will probably increase payment rates in small increments as they have in the past. Those increases trend below the rate of increase in cost of physician practices, but actual per beneficiary costs grow much faster. In other words, if I’m reading the brief and the following figure (about which, more here) correctly, the true 10-year cost of no long-term doc fix is probably even higher than $358 billion.

In comparison, MedPAC’s $200 billion may be a bargain, but may not be cheap enough in this climate of austerity. Ironically, that will likely mean that docs won’t get their long-term doc fix; they are more likely to get an interim fix that keeps them on the same path they’ve been on. Given all this, I’m not so sure why so many of them don’t like the interim fixes. True, they’re not good policy, and they lead to farcical budgeting. But they also put more money in docs’ pockets relative to proposed reforms. Except perhaps to primary care physicians, who are relatively underpaid, the status quo seems like a pretty good deal for many physicians compared to alternatives. Am I wrong?