Do we spend too little on substance use treatment? Let’s examine some numbers:

According to figures presented in a recent Health Affairs paper by Mark, Levit, Vandivort-Warren, Buck, and Coffey, the potential need for substance use treatment in the US is large.

In 2008, 22.2 million people age twelve or older (8.9 percent of that population) were identified as having substance abuse or dependence problems. During the same year, only about 4 million received treatment, 2.2 million of those from self help groups. […]

Analyses […] indicate that […] 5.5 million [uninsured people] were classified as having substance dependence or abuse disorders in the past year. Thus, millions of people with mental illness and substance use disorders could benefit from improved access to insurance coverage.

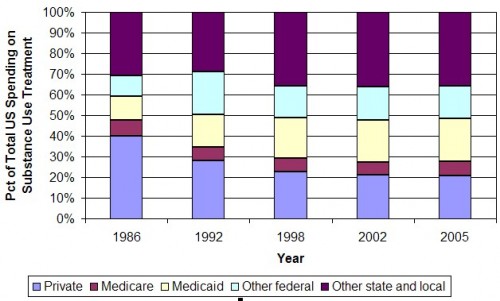

In 2005, the most recent year examined in the paper, US spending for substance use treatment was dominated by public-sector funds: 36% non-Medicaid state and local, 21% Medicaid, 7% Medicare, and 16% other federal (includes block grants and spending by the VA and DoD). The remaining 21 percent was spent by private sources. This breakdown has changed over the years, as shown in the figure below, which I made from data in Exhibit 4 of the paper.

Notice from the figure that the proportion of substance use treatment spending from private sources has declined from 40% in 1986 to nearly 21% in 2005. The difference has been picked up by public sources excluding Medicare, which has remained nearly constant. This shift reflects a private sector “boom and bust.” The authors explain,

The 1980s was a time of expanding insurance benefits and broadened access to substance abuse treatment providers. However, by the mid- to late-1980s, employers were increasingly alarmed by spiraling health care costs. Substance abuse treatment, in particular, was perceived as an example of inflated spending—a perception enhanced by the growing private treatment industry.

The result was managed care restrictions on reimbursement for substance abuse treatment in hospitals. Restrictions included limitations on the commonly used treatment paradigm of a twenty-eight-day inpatient rehabilitation stay.

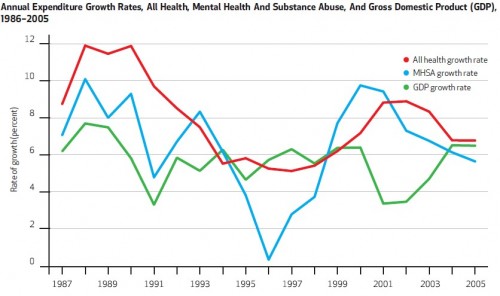

As shown in the following figure from the paper, growth in spending on mental health and substance abuse has not kept pace with that of health care in general (with the exception of 1998-2001). However, like health care in general, growth in spending on mental health and substance abuse has been above GDP growth (with the exception of 1994-1998 and 2005).

Growth in substance abuse treatment spending has actually been even slower than indicated in the figure above:

During the study period (1986–2005) both mental health and substance abuse spending grew more slowly than all health spending: 4.8 percent annually for substance abuse, 6.9 percent annually for mental health, and 7.9 percent annually for all health.

In 1998, total spending (public and private) on substance abuse treatment was $67 billion. The economic burden of alcohol and drug abuse that year has been estimated to be $328 billion. (See page 27 of the link. I have not yet seen a more recent estimate; are you aware of one?) That is, the cost to society of substance use was five times the amount spent on treatment. These other costs include those associated with lost productivity, crime, and prosecution/criminal justice.

In light of the apparent gap between need and societal cost on the one hand, and level and growth in spending on the other, it’s worth asking, should we be spending more on substance use treatment?

UPDATE: The estimates of the economic burden of substance use are higher than I had indicated in the original post.