Does the U.S. overspend on health care? Graphs Aaron has posted suggest so. Not all economists would agree.

With an aim of expanding my knowledge of the literature, a colleague suggested I read “The value of life and the rise in health spending,” by Robert Hall and Charles Jones (The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2007; ungated PDF here). Maybe that colleague was trying to mess with me because it was no fun to read at all. It’s a very dense paper! Its message may be challenging to some, but I find it plausible.

As we get older and richer, which is more valuable: a third car, yet another television, more clothing—or an extra year of life? There are diminishing returns to consumption in any given period and a key way we increase our lifetime utility is by adding extra periods of life.

Standard preferences imply that health is a superior good with an income elasticity well above one. As people grow richer, consumption rises but they devote an increasing share of resources to health care. […]

Our numerical results suggest the empirical relevance of this channel: optimal health spending is predicted to rise to more than 30 percent of GDP by the year 2050 in most of our simulations [with a range from 23% to 45% of GDP], compared to the current level of about 15 percent.

Mumbo jumbo to you? In brief and taking some liberties with the economic niceties, Hall and Jones are saying that as you become wealthier you’ll devote an increasing fraction of your wealth to health spending. That’s because extending your life is the most efficient way to increase your happiness. Buying another bauble only to die the next day is less satisfying. I buy that (not the bauble, but the idea that we’ll spend more and more of our wealth on health).

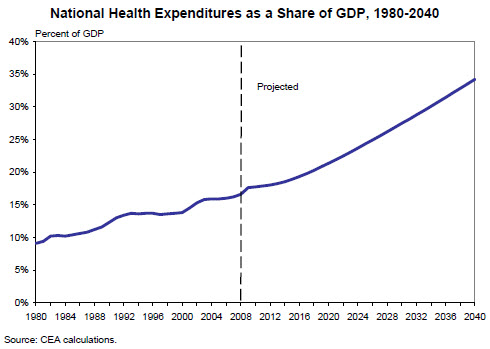

The upshot of this, after they grind it through a fancy model about which I will not burden you,* is that they expect the optimal (utility maximizing) level of U.S. national health expenditures (NHE) to at least double by mid-century. Well, they at least got one thing right. We’re on track to hit that level of spending. Take a look at the Council of Economic Advisors’ NHE projection as of June 2009:

It looks to me like we’ll hit NHE/GDP of 30% by 2035 or so. It’s hard to say exactly what the predicted value will be by 2050 but my best guestimate from the CEA’s graph above is that it’ll be in the neighborhood of 40%. Is that optimal? Hall and Jones say so, but I’m not ready to commit, not when there are so many market failures in health care.

Anyway, the U.S. may spend way more than what is expected based on a linear regression of health spending on wealth using OECD nation data, but who says the health spending-wealth relationship best modeled with a linear regression? Two things about this: (1) I don’t think the regressions Aaron showed are linear in wealth. I see some curvature in those plots. Perhaps the square of GDP was included in the regression. Aaron? (2) Don’t we expect a consistent relationship between GDP and health spending? How, then, do we explain Norway and Luxembourg, which have high GDPs and health spending far below what their wealth levels would predict?

Without taking a stand on whether 30%+ of GDP on health will be the optimal spending level in 2050, there is still reason to be concerned about health spending. However many dollars we spend, are we getting optimal value for them? In other words, could we spend less but more wisely and achieve the same life-extending results? Another question is, how will the spending be distributed? Will only the very wealthy be able to afford the fantastic health technologies of 2050? Lastly, how will that spending be financed? What mix of taxation, government debt, personal responsibility, and chicken barters will support the health spending of 2050? These questions are sufficient to heighten my own concern about health care spending even if 30%+ GDP spending on health care in 2050 is indeed optimal, and even if it is not.

I actually think we can and will do very little to slow the growth of spending in the U.S. However, we may be able to answer and address the questions: How will we spend? For whom will we spend? And with what level of waste?

If you want to read more about this type of thing, as I do, Hall and Jones include the following brief literature review that will serve as guidance:

Our work is a theoretical counterpart to the recent empirical arguments of David Cutler and others that high levels and growth rates of health spending may be economically justified [Cutler et al. 1998; Cutler and McClellan 2001; Cutler 2004]. On the theoretical side, our approach is closest in spirit to Grossman [1972] and Ehrlich and Chuma [1990], who consider the optimal choice of consumption and health spending in the presence of a quality-quantity tradeoff. Our work is also related to a large literature on the value of life and the willingness of people to pay to reduce mortality risk. Classic references include Schelling [1968] and Usher [1973]. Arthur [1981], Shepard and Zeckhauser [1984], Murphy and Topel [2003], and Ehrlich and Yin [2004] are more recent examples that include simulations of the willingness to pay to reduce mortality risk and calculations of the value of life. Nordhaus [2003] and Becker, Philipson, and Soares [2005] conclude that increases in longevity have been roughly as important to welfare as increases in nonhealth consumption, both for the United States and for the world as a whole. Barro and Barro [1996] develop a model in which health investments reduce the depreciation rate of schooling and health capital; health spending as a fraction of income can then rise through standard transition dynamics.

References

Cutler, David, Your Money or Your Life: Strong Medicine for America’s Health Care System (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004).

——, and Mark McClellan, “Is Technological Change in Medicine Worth It?” Health Affairs, XX (2001), 11–29.

——, Mark B. McClellan, Joseph P. Newhouse, and Dahlia Remler, “Are Medical Prices Declining? Evidence from Heart Attack Treatments,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, CXIII (1998), 991–1024.

Grossman, Michael, “On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health,” Journal of Political Economy, LXXX (1972), 223–255.

Ehrlich, Isaac and Hiroyuki Chuma, “A Model of the Demand for Longevity and the Value of Life Extension,” Journal of Political Economy, XCVIII (1990), 761–782.

——, and Yong Yin, “Explaining Diversities in Age-Specific Life Expectancies and Values of Life Saving: A Numerical Analysis,” NBER Working Paper 10759, 2004.

Schelling, Thomas C., “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” in Problems in Public Expenditure Analysis, Samuel B. Chase, ed. (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1968).

Usher, Daniel, “An Imputation to the Measure of Economic Growth for Changes in Life Expectancy,” in The Measurement of Economic and Social Performance, M. Moss, ed. (New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1973).

Arthur, W.B., “The Economics of Risk to Life,” American Economic Review, LXXI (1981), 54–64.

Shepard, Donald S., and Richard J. Zeckhauser, “Survival versus Consumption,” Management Science, XXX (1984), 423–439.

Murphy, Kevin M., and Robert Topel, “The Economic Value of Medical Research” in Measuring the Gains from Medical Research: An Economic Approach, Kevin M. Murphy and Robert Topel, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Nordhaus, William D., “The Health of Nations: The Contribution of Improved Health to Living Standards” in Measuring the Gains from Medical Research: An Economic Approach, Kevin M. Murphy and Robert Topel, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Becker, Gary S., Tomas J. Philipson, and Rodrigo R. Soares, “The Quantity and Quality of Life and the Evolution of World Inequality,” American Economic Review, XCV (2005), 277–291.

Barro, Robert J., and Jason R. Barro, “Three Models of Health and Economic Growth,” Harvard University working paper, 1996.

* I confess to not having fully read and understood the details of the model myself.