This is a TIE-U post associated with Karoline Mortensen’s Introduction to Health Systems (UMD’s HLSA 601, Fall 2012). For other posts in this series, see the course intro.

Also, this will be my last TIE-U post this semester. Moreover, I am not planning to run TIE-U again, though it is always possible I’ll restart it someday.

In The (Paper)Work of Medicine: Understanding International Medical Costs, David Cutler and Dan Ly make a good point. In comparing U.S. health care spending and its growth to that of other wealthy nations, even if one concludes it’s the prices, stupid, it’s valuable to push the analysis a bit further. One wants to know

whether factors earn different returns across countries and whether more clinical or administrative personnel are required to deliver the same care in different countries.

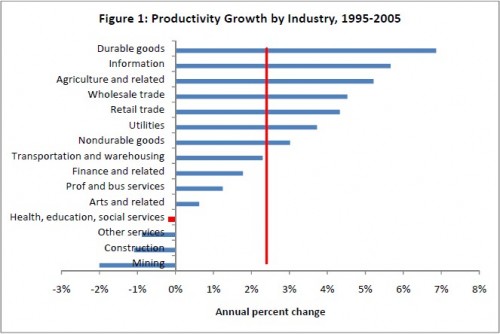

As we know from prior posts, the wages of health care workers are not going up at anything like the rate of growth of health care spending. In fact, they’re not even keeping up with inflation. That leads one to suspect that more clinical or administrative personnel are at the heart of price growth. Indeed, according to Cutler’s own work, and that of others, productivity growth is negative in health care, which itself implies it is taking more inputs, like labor, to produce the same output.

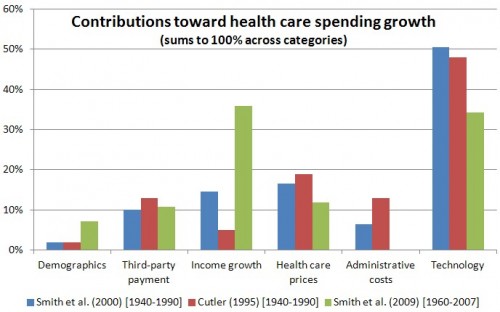

Culter’s work also suggests that administrative costs growth is a substantial contributor to rising health care spending.

A good deal, but not the entirety, of the paper by Cutler and Ly is about U.S. health care administrative costs as compared to those of Canada. You can probably guess their conclusion: U.S. administrative expenses are much higher. The authors advise,

Because the federal government is involved in so much of health care, it would be natural for the federal government to take the lead in addressing administrative issues. For example, the government could require physicians’ offices, hospitals, and insurers that participate in Medicare, Medicaid, or the soon-to-be-created insurance exchanges to use common credentialing forms, to expand the range of electronic interchange they accept, and to standardize billing, enrollment, and renewal information.

(For more along these lines, see also the recent NEJM piece by Cutler, Wikler, and Basch.)

The private sector has failed to bring about the type of cost-reducing reforms Cutler and Ly suggest. Why? As the authors point out, it’s an obvious collective action problem. Any one insurer cannot move the entire system, and even if one invests in streamlining operations for itself, it may not capture a sufficient return to justify the investment. Cutler and Ly offer another hypothesis.

A second potential reason for the persistence of high administrative costs in health care is that complexity might be valuable to insurance payers if it lowers what they ultimately pay for health care. For example, denying claims saves an insurance company money if a service is never reimbursed or if the present value of payments for services that are eventually reimbursed is reduced. Delay may also discourage physicians from providing some services entirely.

If Cutler and Ly are right, then reducing administrative hurdles might actually increase health care spending. In fact, there is precedent for that. To the extent that it does so in ways that don’t promote health, that’s just waste of another sort. Yet, it’s hard to get excited about hassles as cost control. The engineer in me hopes Cutler and Ly are wrong, but that doesn’t mean they are.