On July 9th, I spent the day at the Cancer Centre meeting with my radiation oncologist, and I learned a lot. I’ll tell you about my cancer, what might have caused it, and what that tells us about how we can prevent cancers like this.

My cancer is an ~80 cubic centimetres, p16 positive, oropharyngeal, squamous cell carcinoma (p16+ OPSCC). ‘Carcinoma’ means that this cancer originated from epithelial cells. Epithelial cells form the surface of your throat and mouth. ‘Squamous cell’ indicates the type of epithelial cells; squamous cells are flat, like tiles or plates. ‘Oropharyngeal ‘tells us that the carcinoma is in the middle of my throat. P16+ means that when the pathologist stained the biopsy sample in a certain way, it revealed that a high-risk variant of the human papillomavirus (HPV) helped cause this cancer. 80 cc ( = ~5 inches3) indicates that the carcinoma is, unfortunately, large.

The radiation oncologist inserted a thin tube with a camera and an LED into my nostril and threaded it down into my mouth. This felt weird but not painful. The camera showed us the inside of my throat. And there was the tumour: an irregularly surfaced lump, vast on a big screen.

Radiation oncologist: “That’s why you can’t swallow well. I’m amazed that the air can get around it. Actually, how do you even breathe?”

<Me: [silent] Like I’m supposed to know?>

RO: “If your throat swells from the radiation, you won’t be able to breathe. Maybe we’ll need to do a tracheotomy before we start.”

<Me: [silent, but SHOUTING] SAY WHAT?>

If it wasn’t clear already, this game is played for real money.

So what caused this cancer? Tobacco and alcohol are the principal risk factors for throat and mouth cancers, but I have never smoked, and I don’t drink that much.

However, the staining of the biopsy sample showed that I was at some time infected with a strain of HPV that can cause this type of cancer (not all strains do). HPV can cause cancer in the pharynx and the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, or anus. In the US in 2019, there were 52,840 new cases of these cancers and 12,100 deaths.

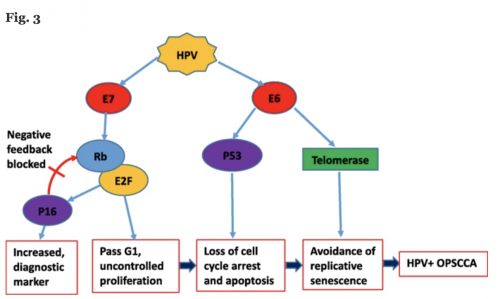

So how does HPV cause cancer? When a virus infects a cell, the genes in the virus use materials in the cell to make proteins that eventually replicate the virus. However, these proteins can have additional consequences. In the dangerous strains of HPV, we call some of the viral genes oncogenes because they influence the cell to transition to unrestrained growth, that is, cancer.

The HPV oncogenes produce oncoproteins, in this case, the E6 and E7 oncoproteins. The oncoprotein E7 leads to a cascade of events, one of which is the overproduction of the p16 protein. When the pathologist stained my biopsy sample, the overproduction of p16 became visible, and he or she used this marker to diagnose the carcinoma as HPV+ ( = p16+). E7 also damages the brakes on the cell reproduction cycle, which helped set the stage for uncontrolled proliferation.

The E6 oncoprotein interferes with the action of the p53 protein, a famous molecule that is essential in DNA repair. P53 is also critical to safety mechanisms in cells that trigger apoptosis — cell death — when dangerous problems develop in cell reproduction. E6 also helps preserve telomere length in the cell’s chromosomes. Diminishing telomere lengths are part of the cellular ageing processes. By keeping them long, E6 helps make the cell immortal.

The transition from healthy to cancerous cells takes a long time following HPV infection. Nevertheless, the upshot of these sequences of events is that the cell becomes long-lived, and it reproduces in an uncontrolled way, which is to say it becomes an HPV+ OPSCC, like the tumour I saw on the screen.

But how, you ask, did I get infected with HPV in the first place? Let’s not be coy:

Human papilloma viruses are… spread through vaginal, oral and anal sex. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, affecting more than half of sexually active individuals at some point during their lives… The time lag between an oral HPV infection and the development of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer is estimated at between 15 and 30 years. As such, the rise in [OPSCC] seen since the 1990s in large part reflects changes in sexual practices in the 1960s and 1970s.

I was infected as part of a viral epidemic. It most likely happened while I was having oral sex during college.

I regret nothing. Tell it like it is, Edith!

Warning: the HPV epidemic has never gone away. However, HPV+ OPSCC and cancers of the penis, anus, vulva, vagina are preventable with HPV vaccines. Cervical cancer — the biggest killer — is almost entirely preventable. The vaccines are cost-effective and exceptionally safe. Sixty-seven million doses were administered from 2006 to 2014. Those doses resulted in 25,000 reports of adverse events (< 4 per 10,000 doses). However, only 8% of those reports were serious (~3 in 100,000 doses). Importantly, a report of an adverse event means that it happened; it does not necessarily mean that the vaccination caused that event. For example, the serious adverse events included 85 deaths, but the deaths had no typical pattern, as would be expected if the vaccine caused them.

Nevertheless, in 2013, less than 40% of female patients and less than 15% of male patients had been vaccinated. There are at least two reasons. First, there has been political resistance to HPV vaccination.

Vaccine coverage is hindered by public perceptions regarding HPV’s status as a sexually transmitted infection and dissent over the recommended age of vaccination. Social conservatives have countered vaccine mandates with the argument that they infringe upon parental rights to discuss the topic of sex on their own terms. Pro-abstinence activists raise similar concerns that HPV vaccination may increase teenage promiscuity, though there is no evidence for this claim… Finally, several studies have shown that parents fail to vaccinate due to misperceptions about the risk of HPV infection.

Some of these misperceptions about vaccine risk stem from false claims spread by Michelle Bachman during her failed presidential campaign in 2011.

The second reason relatively few youths are vaccinated is that getting vaccinated is a bother. It requires three shots to prevent an adverse health outcome that won’t occur, if it ever does, for decades. That feels, I imagine, like too much trouble.

We need to cultivate the norm that there is a duty, part of our solidarity with our neighbours, that we should endure the mild risks and inconveniences and get vaccinated for HPV. We could save even more lives by accepting a collective duty to get vaccinated for the flu, and, we must hope, soon for the coronavirus. Doing these things would save many tens of thousands of lives each year.