No, I haven’t forgotten about Goldhill’s Catastrophic Care. I’ve just been too busy doing and reading other things to maintain my prior pace of reading and posting about it.

Here’s a basic question I would want anyone reading the book to ask him/herself: “Do I want the full story?” If the answer is “yes” then I think the reader needs to look beyond the book’s pages. I’ll give two examples below.

But first, I need to point out, as I have before, there are some fine passages and ideas in the book. To critique some is not to suggest the whole thing is rubbish. Likewise, to praise others is not to suggest the whole thing is perfect. It’s a mix. I do worry that most readers won’t know that.

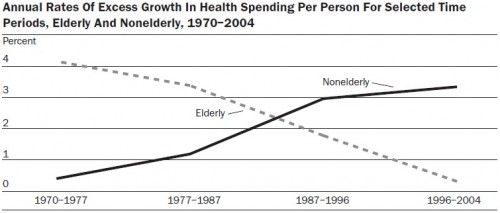

The chapter begins with scorn for Medicare’s hospital prospective payment system (PPS), based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). It’s true, as Goldhill points out, that implementation of that system in 1983 was followed by shorter hospital stays and an increase in the rate of growth in outpatient (and post acute) spending. Goldhill’s conclusion is that it did not bend the cost curve.

Do you want the full story? If so, then you should also consider the work of Chapin White, about which I’ve posted. If you’re motivated, just click over to that post. Read it and consider the charts. I won’t go so far as to say that doing so provides the full story, but I think you have to admit that it adds something important about what Medicare’s various cost control measures have done, including the 1983 hospital PPS.

You should also consider the examples of European countries that have adopted and adapted Medicare’s DRG system, England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden among them. The recent Health Affairs paper on the subject is illuminating. If the DRG system is so problematic, how do residents of these countries receive care of similar or better quality for less than we do in the U.S.? I’ll blog more about that another day. For now, see how the picture is quite a bit more complex?

Later in the chapter Goldhill bemoans the incentives in the drug industry.

In the same way that our administered pricing prevents me-too chronic care treatments from declining in price, it prevents effective antibiotics from climbing in price enough to provide a competitive return on capital.

I agree there are many problems with the drug industry and drug pricing, even in Medicare. What bothers me about the quote above and the nature of the discussion in which it appears is that it gives the impression that the “administered prices” are entirely government-set prices. Medicare does set prices for chronic care treatments, as it does for all hospital and physician services and associated supplies. And, yes, there are ample problems with how it does so. But it is famously barred from setting outpatient drug prices. Those are established by private plans. As such, I would advise changing in the above quote “administered pricing,” which generally means “government pricing,” to “third-party pricing.”

This is important to spell out clearly because one reaction to Goldhill’s thrust could be that we need to privatize more of Medicare. Whether that is or is not a helpful idea depends a great deal how its done. Very often proponents of more private plan involvement in Medicare point to its drug program as an example. And, in some ways, it is a good model. It has not, however, addressed the deep problems in the pharmaceutical industry that Goldhill rightly critiques. Communicating that, I believe, is a step toward the full story.

Other posts in this series are under the Catastrophic Care tag.