Last Monday, I spent the day in a hospital — specifically, an Emergency Department (ED) — dealing with an episode of atrial fibrillation. I’ll explain how this was connected to my cancer, but my principal goal is to call attention to a flaw in the health care I experienced during this episode: ‘Hallway medicine.’ It’s a chronic problem in my home province of Ontario.

The background is that I am recovering from radiation treatment of a tumour in my throat. That radiation has — I hope — destroyed the tumour. Whether or not the tumour is gone, the radiation charred my throat, making it painful to swallow. The difficulty in swallowing makes it challenging to stay well-hydrated.

Dehydration wouldn’t be a big deal, except that I was born with low blood pressure and a slow heart rate (bradycardia). Endurance sports lowered my heart rate still further. During my triathlon days, I once recorded a resting heart rate of 35 beats per minute. (If I got any chiller, I’d be dead.) Unfortunately, I also have a congenital arrhythmia. The neural circuitry inside my atrium — which initiates a heartbeat — somehow got laid out in a non-standard way. (“It’s the same goofy wiring he has inside his head,” sez my physician wife.) This means that I occasionally have random delays — skipped beats — in my heart’s rhythm. But if an already slow heart skips a beat, bad things can happen. It’s as if my autonomic nervous system panics: is this chump’s heart beating at all? This triggers a state of atrial fibrillation, that is, a surge to a dangerously high heart rate (e.g., 160 bpm). Very rapid and irregular heartbeats do not pump blood efficiently. Blood pressure can drop, my brain gets deprived of oxygen, and I pass out. I have spent too much time in heart hospitals, where cardiologists have worked to control this.

OK, that’s complicated, but I promise you it will connect back to my cancer-related dehydration. To paraphrase Derrida, if human biology were simple, word would have gotten around. Now back to my story.

At 1:00 AM last Sunday, I woke up to use the washroom (as we say in Canada). I stood up from my bed and promptly passed out, crashing to the floor. At 10:00 AM, it happened again. My blood pressure was so low that we couldn’t get a reading on our home blood pressure cuff. I couldn’t stand without passing out; I couldn’t even get downstairs to our car so that my wife could take me to the hospital. I had to be taken by ambulance. On the way, the paramedics confirmed what we suspected: I was, for the first time in many months, experiencing atrial fibrillation.

We arrived at the Ottawa Hospital ED. The ambulance drove into a garage, where I was transferred to a bed, efficiently triaged, and the bed was rolled into an alcove in the ED. I was hooked to heart and blood pressure monitors and was rocking 160 bpm, with a blood pressure of roughly 90/60. Doctors and nurses took my history. Ottawa is a small world: the attending physician was Dr. Z, the younger brother of my family physician. My hypothesis was that I had gotten dehydrated. The reduced volume of liquid had reduced my blood pressure, increasing my risk of atrial fibrillation. Dr. Z the Younger agreed, and ordered some blood work to check whether my electrolytes were normal. He also ordered an IV unit of saline solution. It took 90 minutes for the IV to actually happen, but once it did, my heart rate dropped to a steady 60 bpm. That is, I had converted from atrial fibrillation back to normal heart pacing.

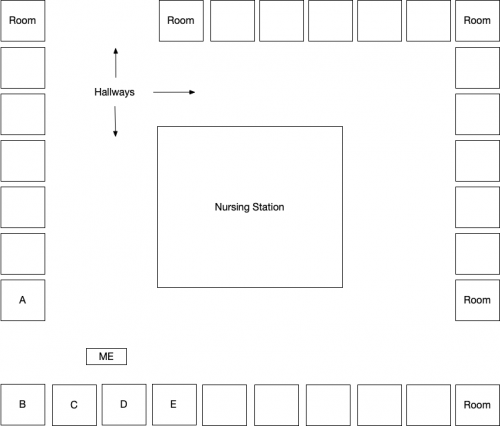

To this point, my care had been exemplary. However, the ED was clearly under substantial stress. Staff were constantly having to stop and disinfect things. Every bed was filled, and I am sure there was a crowd in the waiting room. At this point, the only reason to keep me was to make sure there were no problems in the blood work. So while we waited for those results to come back, they wheeled me out of the alcove and parked my bed in the ED hallway. You can see where I was in the Figure below.

What’s wrong with receiving health care in a hospital hallway? First, someone being cared for in a non-standard location is more likely to get substandard care, if only because it is easy for staff to lose track of them. This wasn’t a great risk for me. I was lucid, no longer in atrial fibrillation, and I was in full view of the nursing station, so I could get care quickly if I needed it. However, it is impossible to rest in a hallway. There was a constant flow of staff and patients around me, so despite having been up most of the night, I couldn’t sleep. Finally, I had no privacy when I spoke with Dr. Z (although, as you can tell, I am not shy about discussing my health problems).

The deeply troubling problem, however, was that I could hear everything in the rooms I was near. My presence in the hallway violated the privacy of the patients in rooms A through E. I won’t provide details, but things happened that I would not have wanted a stranger to overhear.

Why does Ontario have a problem with hallway medicine? The occupancy rates for Ontario hospitals are often near or even above 100%, where occupancy > 100% means that patients are on gurneys in the hall. The problem precedes COVID-19. The provincial government wrote a 2019 report that candidly admits that hospital patients are frequently cared for in hallways. This happens because some areas in the province are served by hospitals with too few beds, either in the ED itself or in the wards where patients ought to be transferred from the ED.

But why hasn’t the province opened more beds? There aren’t more beds because hospital care in Canada costs a lot more than, say Denmark (33% more in 2016, according to the OECD).

One reason is that Denmark, like many other OECD countries, is small, compact, and densely populated. Put up a few, well-spaced hospitals, and every Dane will have a place nearby. Ontario is substantially bigger than Texas. Although most Ontarians live in or near big cities, there are also large, sparsely populated rural areas. To the north, there are vast boreal forests that become tundra where the province hits Hudson’s Bay. These remote areas are almost — but not quite — empty. There are tiny settlements up there, many of them with concentrated poverty and health problems.

Supplying tertiary health care services to rural and remote areas is costly. If you build community hospitals, many of the beds and operating rooms will be empty much of the time. In sparsely-populated areas, the number of people who live close enough to drive to the hospital is simply too small. Nevertheless, unfilled beds and unused ORs still need to be staffed, which is inefficient. But if you don’t build community hospitals, you will spend money instead on long ambulance transports, often by air.

No provincial policy can change the geography of Ontario. So why don’t Ontarians bite the bullet, spend more, and get patients out of the hallways? Perhaps we should. After all, Canada spends considerably less per capita on health care than the US does. However, although Canada spends less on health care than the US, it spends more on other social programs like parental leaves, child care subsidies, education, and unemployment insurance. There isn’t public support for spending less on those services. Moreover, you could argue that spending more on social services and less on health care is a reason why Canadians are happier, better educated, and live longer than Americans.

So if Ontarians do not want to transfer resources from schools to hospitals, opening more hospital beds will require new public expenditures and higher taxes. Surprise: they do not want to do this. Perhaps this is short-sighted; everyone is counting on it being someone else whose hospital bed gets parked in the hallway. Or maybe it is wise: we have a progressive tax system in which high earners pay high marginal rates (DM me on Twitter for details). If those rates rose too much, highly-skilled Ontarians might look for jobs in Arizona or Florida. There aren’t easy answers here.