Because The Incidental Economist is widely read, I am frequently interviewed by Canadian journalists (radio, TV, and print). I want to talk about provincial and national health policy. But the interviewer always wants me to say how it feels to have cancer during the COVID pandemic.

Well, it varies. When I was first diagnosed and learned about my treatment options, it was clear that I had a choice of ordeals. I’ve done ordeals: marathon, triathlon, dissertation. So when the courses of treatment were presented to me, I knew I could do them, and I set about working through the details.

And when I finished radiation therapy, I was elated. Yes, I had lost 30 lbs, my throat was on fire, my neck was swollen with lymphedema, and I was still feeding through a tube. But I was done, over the finish line, and it was going to get better from here. I began planning a recovery — reconstructing my daily writing routine, low carb/high protein diet, and my weekly yoga/strength/cycling routine. It was my Build Back Better plan.

Those programs have lasted, more or less. I am recovering, I am writing, I’m eating well, and I am exercising. But Build Back Better isn’t how life feels.

On the one hand, there is a depth of fatigue in life that is new to me. There is blackness, a singularity of exhaustion in my bone marrow, and it laughs at my self-help routines. It will take months of recovery to clear it if it ever entirely goes away.

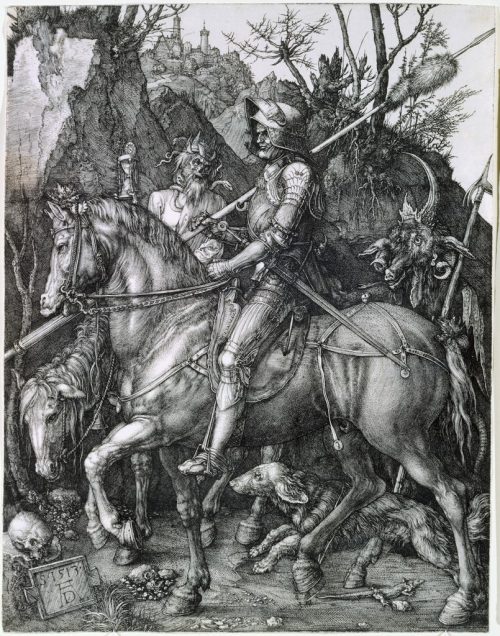

On the other hand, cognitively and emotionally, I’m not at all sure that things will get better. Cancer brings the reality of death up close and personal.

When I chose my treatment plan, the deal was that I had a 75% chance of surviving 5 years. Here’s how I understand this: there are 3 chances in 4 that the radiation has destroyed my tumour. If that’s what happened, I now have more or less the longevity of other 67-year-old males. Conversely, there is one chance in four that cancer has disseminated from my throat. Then, my apparently successful radiation therapy will be followed by new cancer. I’ve been through this with friends, and it has killed them.

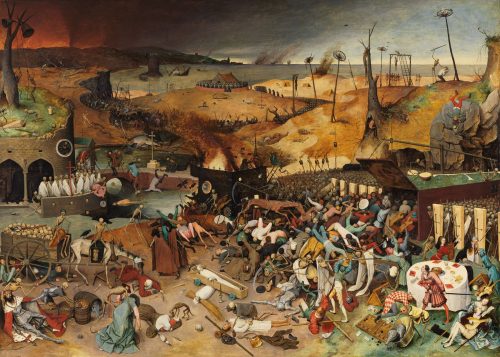

Then, add COVID. I’m now in the intersection of two high-risk categories. I disinfect whenever I see a dispenser. I wear a mask whenever I know that I’ll meet people out of the house. But I’m not perfect, and someday, I’m likely to walk through a cloud of droplets. What happens then?

I don’t obsess about death. I have a purely depressive personality, just the emotional blue notes, without concomitant anxiety. I don’t experience much fear, including fear of death—nevertheless, the actuarial odds condition all my choices. I am always aware that time may be limited.

If not for COVID, we would travel to be with our children in the US. But the border is closed. So the choice is work, and that’s fine. What cancer and COVID press me to ask is, “what do I still have to say that might make a difference?”