In my cancer care so far, shared decision-making between doctor and patient is only half-working. In this post, I ask why.

Shared decision-making occurs when physicians help patients make choices that cohere with both the patient’s values and the best scientific evidence. For example, in my previous cancer post, I described how I had to choose whether to be treated only with radiotherapy or to have radiation with concurrent chemotherapy. In choosing to have radiation-only — that is, no chemotherapy — I was helped by several physicians at the Ottawa Hospital. They answered my questions clearly and respectfully. Interestingly, my doctors disagreed about what I should do, and I was pleased that they were candid about that. Friends and family members in medicine also helped. I am particularly grateful to several physicians and cancer survivors, compassionate strangers who read my posts and wrote to me. Thanks to you all.

So when I think about these interactions, shared decision-making worked superbly for me. I will continue to say this even if the treatment fails because this aspect of the caregiving has been excellent, regardless of the (to-be-determined) outcome.

Except that none of these wonderful interactions matter if the health care system can’t process even simple communications from a patient.

On July 27, I got a call from the radiation clinic, telling me that my first radiation session would be on the 29th. This is lovely because I want to fry this tumour’s ass before it has a further chance to spread. But a few minutes after I hung up, the chemotherapy clinic called to tell me about my first chemotherapy session.

Me: “Sorry, but I thought that I was clear that I had elected not to have chemotherapy.”

Clerk: “No, we have an order for you to start chemotherapy.”

Me: “Dr. X [the medical oncologist] asked me to decide about chemotherapy and let him know. I communicated that on MyChart.” [MyChart is the application that gives patients a (highly restricted) view of Epic, the hospital’s electronic health record.]

Clerk: “You can’t use MyChart for that.” [The clerk was correct. MyChart, at least as implemented here, gives you no means to send a message to a doctor. I had misremembered.] “You have to use the Patient Support Line.” [That was what I had misremembered. I had used the Patient Support Line to get a message to Dr. X, not MyChart.]

Me: “OK, so can you cancel the appointment?”

Clerk: “No, you have to use the Patient Support Line.”

I hung up and called the Patient Support Line, which is a phone robot. When it answered, I recognized its voice, and I recalled that yes, I had called this line to send Dr. X my decision. You might imagine that the Patient Support Line would connect you to a person. Someone who can, you know, support you as a patient? Instead, it’s a barebones phone tree. The Patient Support Line allows you to leave a message, but it’s not clear to me who reads it or what they do with it. Regardless, I once again left my message for Dr. X. So far as I can tell, neither my first nor second message reached Dr. X or anyone who works for him.

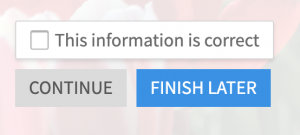

Next, I opened MyChart, and yes, there are my chemotherapy appointments. OK, great, these are calendar appointments, so there should be some way to decline or cancel them, right? No, there is not. Well, then surely there will be a mechanism to mail the person who created the appointment to let them know it is incorrect. If there is, I can’t find it. There is a box that you can check to indicate that the information is correct, but there is no box to note that something is incorrect. The semantics here are puzzling. An unchecked box means either a) the patient ignored this or b) the patient thinks something is wrong. How is that helpful to anyone?

Stop, I tell myself. Don’t spend your time debugging an application for Ottawa Hospital’s IS Department. Instead, let’s go old skool and telephone the Chemotherapy Program. I look up the number, call them, and tell the clerk my story.

Clerk: “This is New Patient Registration. This isn’t something we can handle. How did you get this number?”

Me: “It’s the number that’s listed? Anyway, whom should I call?”

Clerk: “That’s an excellent question. Please hold.”

He puts me on hold. Then, a few minutes later, he returns to the call and — this is pure Canada — he is scrupulously polite with just the faintest hint of reproach that, somehow, I haven’t followed The Rules. But — again, pure Canada — he is helpful:

Clerk: “I’ve sent a message to Dr. X. A nurse will call you to discuss your concerns.”

I hang up, then realize that I forgot to ask whether that means that the appointment has been cancelled. Cynically, I predict that the next call from the chemotherapy office will ask me why I missed my appointment.

But I was wrong. A nurse calls within an hour.

Nurse: “What is your question is about your chemotherapy appointment?”

I tell my story again, and she promises to cancel the appointment. I think the problem is solved.

The loss of my time aside, I haven’t been harmed by this confusion. No one acted badly at any point, and busy people treated me with commendable patience. But measured against the aspirations of shared decision-making, this was a disaster. What’s the point of having a nuanced and sensitive discussion about values, probabilities, and uncertainty when it takes two weeks and multiple phone calls to communicate a simple “No, I do not want this treatment”?

I wasn’t harmed because I am a determined son of a bitch a medical school professor, meaning doctors pay me to tell them what they should think. So by personality and status, I don’t have any trouble raising my voice about my care. But I have someone I am close to, who I’ll call “Jim,” who would have been harmed. Jim is a former middle school teacher with a terrifying autoimmune disorder. He has limited mobility and experiences constant, severe pain. He’s frequently hospitalized and has had far too many surgeries. In my opinion, Jim’s care hasn’t been as good as it should be. But he’s not the kind of person who questions his doctors. If the system sent Jim incorrect chemotherapy appointments, he wouldn’t have interpreted it as system noise, as I did. He would have assumed that the doctor had changed her mind, and he would have sucked it up and done what he thought he was being told to do.

So, what’s the problem with shared decision-making? We imagine that medical care is something that a doctor provides to a patient. Consistent with that view, shared decision-making is presented as an ongoing conversation between a doctor and a patient. See, for example, Dr. Paul Kalanithi’s cancer memoir, in which ‘Emma,’ his empathetic and ‘best-in-world’ oncologist, is there for him whenever he needs her. Unfortunately, these views of medical care and shared decision-making miss something important.

What they miss is that although doctor-patient dyads matter, patients are cared for by systems. Systems are sprawls of often loosely connected people linked by communications networks and institutional practices. Care processes must be structured so that doctors and patients can have conversations that facilitate shared decision-making. But that’s not enough. I need to be able to communicate my choices to the system. These choices should reach every relevant person in my care team. Finally, I should be able to monitor what’s happening and flag problems when care deviates from my understanding of the plan.

This requires (vastly) improved engineering of health information systems. It may also require us to rethink who does what when in the care process. For example, wasn’t the idea that primary care doctors would ‘quarterback’ the care process? What happened to that? These are challenging problems, and I don’t fault anyone. But there is so much work to do.