Given some of the recent developments, I wanted to quickly follow up on my post from last week, which weighed potential consequences of a mandate delay if the administration couldn’t get their act together with HealthCare.gov sometime soon. They’ve since brought on Jeff Zients who has promised front- and back-end functionality by November 30. Moreover, the administration has extended the deadline for enrollment without penalty by six weeks, from February 15 to March 31.

I hardly meant to suggest that delaying the individual mandate for one year would be a carefree policy move (I think I described it as the “worst-case scenario”). But I do think that risk corridors make the prospect—however unlikely and unpalatable—less apocalyptic than if that provision didn’t exist.

To clarify, it’s true that reinsurance and risk adjustment (the other risk mitigation programs in the ACA) are narrowly tailored to redistribute profits and losses between insurers. Under reinsurance, fees collected from insurers are redistributed exchange plans with high proportions of high-risk beneficiaries until 2016. Risk adjustment is a permanent program that shifts funds from plans with relatively healthy enrollees to those with relatively sick populations. These discourage insurers from cherry-picking beneficiaries. But the regulations conceive of risk corridors differently:

The temporary risk corridors program permits the Federal government and QHPs to share in profits or losses resulting from inaccurate rate setting from 2014 through 2016.

I’m not saying that risk corridors were constructed with a delayed mandate in mind. Surely they weren’t! But I do think that they’re a feature that could (very, very temporarily) help insurers weather systemic selection problems, with or without such a delay.

Though Megan McArdle doesn’t seem to share my cautious optimism with regard to risk corridors, she makes a good point about the role of subsidies in mitigating adverse selection. This was echoed in the comments on last week’s post, and it’s something Austin has touched on previously.

Jonathan Cohn summarized this incredibly well:

What you may not realize (because few people do) is that the subsidies, by design, protect people from rising premiums. The law basically dictates what these folks pay for the typical, “silver-level” Obamacare plan, no matter what the insurer charges. This is critical. It means that rising premiums won’t affect the willingness of those people to enroll—which means, in turn, they’d still have incentive to sign up next year, as long as the technological bugs were gone and Obamacare online was working. (Subsides were a missing element of those ill-fated reform experiments in New Jersey and elsewhere.)

The exchanges could experience adverse selection with or without the mandate in place during the first year. But a “death spiral” isn’t some inevitable consequence of that; the phenomenon requires a stepwise cycle of prices rising and people dropping coverage. By limiting price increases borne by beneficiaries, eliminating incentives to drop coverage—and thus, future price increases—subsidies create a kind of ceiling on adverse selection.

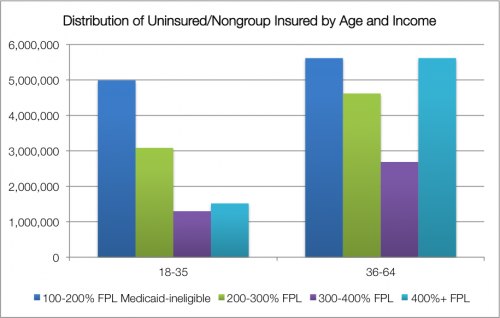

About three-quarters of people we might expect to shop on the exchanges (those who are currently uninsured or have individual coverage, and won’t qualify for Medicaid) have incomes below 400% FPL. The chart below* breaks out that population by age and income level.

People above 400% of the poverty line could still encounter rate increases, but those should be fairly tempered by the ubiquity of subsidies. Even if enrollment through HealthCare.gov is distorted by the website’s glitches, insurers won’t be completely blind in pricing for 2015; functional state exchanges (like Kentucky’s) will offer some guidance on what “normal” enrollment expectations might look like.

Obamacare’s “death spiral” woes are overblown. The law was designed to survive a messy rollout.

* You can find the data used for this chart, its methodology, and a further breakdown of the 18-35 set here.

Adrianna (@onceuponA)