Forthcoming in the Journal of Health Economics, Geir Godager reanalyzes data from a study by Heike Hennig-Schmidt, Reinhard Selten, and Daniel Wiesen, about which I blogged in 2011 (ungated, working paper version of Godager’s manuscript is here). To refresh your memory, here’s a bit from that 2011 post:

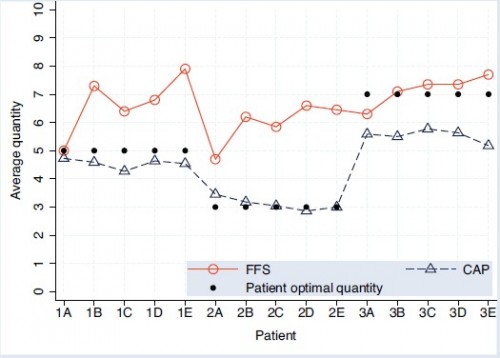

In a controlled setting, the researchers asked medical students to choose the quantity of medical care to provide to hypothetical patients enrolled in either fee-for-service (FFS) or capitated insurance plans [CAP]. Under the former, physicians are paid for each additional unit of care. Under the latter, they receive a lump-sum payment independent of units of care provided. In the experiment, quantity of care is an amount indexed by the integers 0 (no services) to 10 (the most services). In advance of making the quantity selection, the physician has full information about how the quantity selected will affect payment, costs, and profit (or income) and how it will benefit the patient. […]

A-E are the (abstract) illness types and 1-3 index how much medical care would be optimal. The solid, black dots show the optimal level of care. Patients of type 1 (1A, 1B, etc.) would do best with 5 units of care, etc. Notice that under both payment systems, actual quantity provided is correlated with what would be optimal, highest for type 3 patients, lowest for type 2. So, patient needs matter. Still, patients needs don’t tell the whole story. Provision of care under both payment types differs from optimality, most strongly for types 1 and 2 under FFS and type 3 under CAP. Finally, CAP levels of care are systematically lower than under FFS.

After reanalysis, Godager reports,

In this paper, we investigate physician altruism toward patients’ health benefit using behavioral data from Hennig-Schmidt et al.’s (2011) laboratory experiment conducted with medical students deciding in the role of physicians. In particular, we measure individuals’ valuations of patient health benefits when choosing quantity of medical services.

We find that most subjects attach a positive weight to patients’ health and, further, we observe substantial heterogeneity in the degrees of physician altruism. Our results indicate that some subjects attach a higher value to their own profit than to the patient benefit (26%), while others either attach equal weights to profit and health benefit (29%) or put an even higher weight on the patient (44%).

Translation: More than half the study subjects (medical students) value their own profit as much or more than their (hypothetical) patients’ health. I neither find this surprising nor alarming. First of all, these are students facing paper patients, not patients in the flesh. Though that’s probably relevant to the findings, I still think that practitioners facing actual patients place some value on their own profit. Some of them probably do value that profit as much or more than their patients’ health.

Even if we don’t like to think about that (likely) fact, it behooves us to accept it. The model that the doctor always and only cares about what’s best for the patient is old fashioned and, frankly, dangerous. Even if and when it’s true, patients would be better served if they played a more active role in their own care. Don’t presume your doctor’s values and incentives are aligned with your own. Ask questions. Do research. Behave like the consumer you should be. It’s your body, health, and life. And, if your doctor isn’t responding the way you’d like, fire him.

Full disclosure: I just fired one of mine.