Obama’s “fix” for the individual market has a lot of potential holes, apart from whether it’s even legal. First, state insurance commissioners need to decide whether or not to implement the policy. At least some states (Washington and Arkansas) won’t. Even if states adopt the provision, there’s nothing to suggest they would compel insurers to continue offering their plans into 2014, so they may be canceled anyway.

Industry expert Bob Laszewski had this to say earlier in the week:

Cancellation letters have been sent. Their computer systems took months to program in order to be able to send the letters out and set up the terminations on their systems. Even post-Obamacare, the states regulate the insurance market. The old products are no longer filed for sale and rates are not approved. I suppose it might be possible to get insurance commissioners to waive their requirements but even if they did how could the insurance industry reprogram systems in less than a month that took months to program in the first place, contact the millions impacted, explain their new options (they could still try to get one of the new policies with a subsidy), and get their approval?

But let’s set all that aside, and say that insurers in some states bend to consumer demand and decide to extend plans. There’s fear that it would cause selection into exchange plans to be too adverse because many of the “good risks” will stay in plans that were supposed to be canceled. Would this be catastrophic to reform, writ large? Probably not. Consider the following:

- Risk corridors—which I summarized in October—provide a pretty generous buffer against all things unexpected through the end of 2016 (beyond that, we get into trouble—but the administration is only talking about a one-year deal, so far). The short version is that risk corridors are insurance for the insurers, so a bad risk pool in year one wouldn’t cause the market to unravel. The administration’s letter to insurance commissioners indicates that HHS will “explore ways to modify the risk corridor program final rules to provide additional assistance”, making them all the more important.

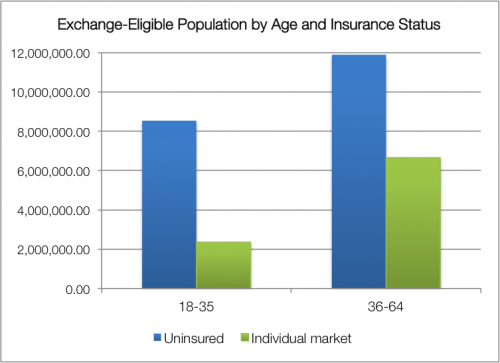

- The majority of people primed for the exchanges are uninsured, not coming from the individual market. It’s true that the uninsured are, on average, less wealthy and may also be less healthy. But the individual market also skews older, with individuals over 35 more likely to enroll than their younger counterparts. The young-old distribution of the uninsured is a little more equal, as you can see in this chart.* It’s a tricky business to try predicting consumer behavior—income and subsidy availability will matter, too—but it’s worth noting that people with nongroup plans only makes up about a third of the prospective exchange population; the impact of losing some people from the individual market may be overstated.

- The individual market is volatile. A Health Affairs study found that the median duration of these plans clocks in around eight months, with half lasting less than six months and two-thirds less than a year. This doesn’t necessarily reflect sick people are being dropped because of their health status—for many healthy individuals, nongroup plans are transitional coverage that they acquire while between jobs. The effective shelf life of these noncompliant plans is already short, and when new people cycle into the individual market, they’ll be required to shop on the exchanges.

I don’t mean to suggest that this is pragmatic policy. It’s burdensome to insurers who canceled their plans in accordance with the ACA (and who don’t seem very keen on uncanceling them, anyway). In a world where the website was functional, this move wouldn’t be so politically necessary. Besides the president’s ill-chosen “if you like your plan, you can keep it” promise, the administration is facing a big mess if (when?) people experience coverage lapses because their plans are canceled and the HealthCare.gov glitches prevented them from buying new coverage by December 15.

Like everything else involving the exchanges, this story is going to unfold at the state level, not nationally. It sets up an interesting tension: refusing to adopt President Obama’s fix could be seen as “a full-throated defense of the Affordable Care Act”, which Sarah Kliff noted following Washington state’s decision to decline. But California—the state leading the nation in implementation—may be trying to accommodate the policy.

Remember that this time last month, we were kicking around the idea of delaying the individual mandate for a year (which, frankly, isn’t off the table until the website is functioning well). The “like it/keep it” fix might be more confusing, but ultimately it’s less disruptive than mandate delay would be. Scale your histrionics accordingly.

*The chart uses 2011 Census data for individuals above the poverty line, omitting the Medicaid-eligible. Relevant methodology here.

Adrianna (@onceuponA)