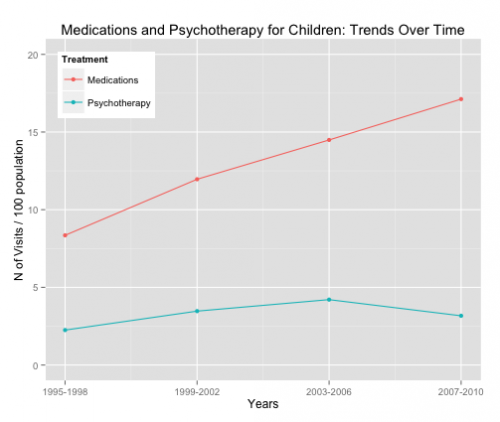

The use of psychotropic drugs with kids has increased rapidly. For example, the rate of medication-related mental health visits for children roughly doubled from 1995 to 2010.

This increase raises many concerns. Psychotherapeutic drugs are very commonly used “off-label” with children meaning that their use with children has not been approved by the FDA. Off-label prescribing by physicians is legal. A physician can prescribe a drug for any use once the FDA has approved a drug for one use, and patients often benefit from off-label drugs.

However, “off-label” often implies that there isn’t a deep or consistent foundation in data that support the use of these drugs with kids, because the drug manufacturers would have pursued FDA approval if they had sufficient evidence. Many of the off-label uses of psychotherapeutics with kids lack a strong evidence base. This is a particular concern, because it is certain that many of these drugs have significant short term side effects and there are good reasons to worry that they may have long term effects on children’s development.

How and why did the off-label use of psychotropic drugs grow so quickly? One possible explanation is ‘detailing,’ the practice of having pharmaceutical company representatives visit doctors to promote drugs. Having a representative visit a doctor is legal, but many academic medical centers have passed rules restricting sales reps’ access to doctors and limiting the inducements that the reps can offer. Moreover, there are many restrictions on how pharmaceutical companies are allowed to promote the off-label use of a drug.

Ian Larkin, Desmond Ang, Jerry Avorn, and Aaron Kesselheim looked at the effect of restrictions on detailing on prescriptions of psychotherapeutic drugs for children.

Some academic medical centers (AMCs) restrict “detailing” by pharmaceutical sales representatives, or the promoting of drugs directly to physicians via sales calls, to reduce the effect of such marketing on physician prescribing. With data from thirty-one geographically diverse AMCs and their affiliated hospitals, we used a difference-in-differences model to estimate the effect of anti-detailing policies on off-label prescribing of antidepressants and antipsychotics by pediatricians and by child and adolescent psychiatrists in the period January 2006–June 2009.

They used a large database of prescriptions to examine changes in the use of drugs that were on-label (FDA approved for children) versus off-label and drugs that were promoted versus not promoted. Detailers promote brand name drugs because these give manufacturers large markups. They do not promote generic drugs.

Larkin et al. found that

after the introduction of [policies restricting detailing], prescriptions for off-label use of promoted drugs fell by 11 percent, consistent with the ongoing presence of off-label marketing to physicians.

That is, when academic medical centers set policies that restricted detailing, doctors wrote fewer prescriptions for promoted drugs. Importantly, this occurred for on-label and off-label prescriptions, which drug reps should not have been promoting.

These results suggest that pharmaceutical sales representatives promoted drugs not approved for pediatric use and that policies that restrict detailing by those representatives reduced such off-label prescribing.

These results justify restrictions on detailing. But such policies are only part of the solution. What we need is more research to clarify the circumstances in which current off-label use of drugs actually benefit kids. And even more importantly, we need more research to develop better and safer medications and psychotherapies.

ADDENDUM: There is a fascinating side issue here. I don’t have data on this, but I bet that when physicians prescribe psychotherapeutic drugs for children, they rarely tell parents that this use has not been approved by the FDA. Zain Mithani points out that this raises an ethical issue:

it should seem strange that physicians commonly prescribe drugs without informing patients that these drugs have not been approved for the use in question. Most patients believe, rightly, that all drugs prescribed by physicians have been approved by the FDA. What most patients do not know or question is whether a given drug has received FDA approval for a specific purpose.