The following was originally posted on the AcademyHealth blog earlier this year.

In 2010, Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley published a report on health care cost drivers in the state. The report concluded that prices paid to hospitals in Massachusetts

are not correlated to (1) quality of care, (2) the sickness of the population served or complexity of the services provided, (3) the extent to which a provider cares for a large portion of patients on Medicare or Medicaid, or (4) whether a provider is an academic teaching or research facility. Moreover, (5) price variations are not adequately explained by differences in hospital costs of delivering similar services at similar facilities.

Price variations are correlated to market leverage as measured by the relative market position of the hospital or provider group compared with other hospitals or provider groups within a geographic region or within a group of academic medical centers.

A similar theme has been struck in examinations of hospital markets in Virginia, Oregon, California. (More literature on hospital market concentration is summarized here and here.)

A paper published in Health Affairs in February provides evidence that is in some ways consistent and in others inconsistent with the conclusion of the 2010 Massachusetts report. Chapin White, James Reschovsky, and Amelia Bond examined hospital claims data for the families of non-elderly autoworkers and retirees in 13 Midwestern markets, including 110 hospitals.

In contrast to Coakley’s study, White et al. found that high-price hospitals were more likely to be major teaching hospital, to have a more private/less Medicare payer mix, to have a higher disproportionate share ratio (DSH, which measures the share of patients with low incomes, as would be the case for Medicaid enrollees), and a higher DSH revenue share.

High-priced hospitals were not distinguishable from low-priced hospitals on most dimensions of quality, but they were statistically significantly of lower quality according to measures of surgical deaths and blood clots among surgical patients. They were statistically significantly of higher quality according to 30-day, risk-adjusted mortality rates for heart failure patients.

However, high-priced hospitals were much more likely to be nationally ranked by U.S. News & World Report for cancer, cardiology, gynecology, or orthopedic care—often taken by patients as a measure of quality. However, according to the authors, those rankings “are based largely on hospitals’ reputations among physicians,” not on clinical indicators of high-quality care.*

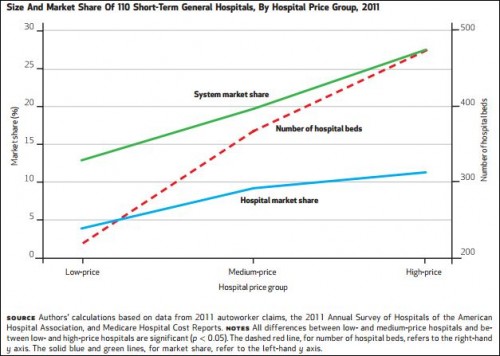

The findings are consistent with the Massachusetts report in an important respect: high-priced hospitals have greater market power, as illustrated in the chart below.

High-priced hospitals are also more likely to offer specialized services like neonatal intensive care, level 1 trauma care, heart transplants, and have a burn unit.

Hospital prices vary considerably within local markets, even after adjustment for teaching activities and differences in the complexity of cases treated by different hospitals. Two predominant narratives have been offered to explain this disparity: First, high-price hospitals have a special mission and unique characteristics that increase their costs and for which they should be compensated; and second, some hospitals have market power that allows them to negotiate high prices with private health plans and operate under little pressure to contain costs.

This study offers support for both narratives. We found that high-price hospitals within markets were more likely to be engaged in medical education; offer specialized, expensive services typically associated with tertiary care hospitals; and serve a higher percentage of low-income (and poorly reimbursed) patients. But high price hospitals also clearly enjoyed dominant market positions. Both their large size and their membership in even larger hospital systems made it difficult for health plans to negotiate lower prices with them.

The authors conclude that the findings highlight “speed bumps” in “attempts to steer patients away from higher-priced providers.” Excluding from networks high-reputation hospitals that offer specialized services could harm enrollees’ access to the care they need and expect. Potentially promising and different approaches includes the use of reference pricing, though that can only work for services that are provided at a wide range of hospitals.

As James Robinson and Timothy Brown suggest, reference pricing may help payers counter the growing market power of high-clout providers.

* This point is disputed.