From Alan Schwarz in The New York Times:

Twenty years ago, more than a dozen leaders in child psychiatry received $11 million from the National Institute of Mental Health to study an important question facing families with children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Is the best long-term treatment medication, behavioral therapy or both?

The widely publicized result was not only that medication like Ritalin or Adderall trounced behavioral therapy, but also that combining the two did little beyond what medication could do alone. The finding has become a pillar of pharmaceutical companies’ campaigns to market A.D.H.D. drugs, and is used by insurance companies and school systems to argue against therapies that are usually more expensive than pills.

But in retrospect, even some authors of the study — widely considered the most influential study ever on A.D.H.D. — worry that the results oversold the benefits of drugs, discouraging important home- and school-focused therapy and ultimately distorting the debate over the most effective (and cost-effective) treatments. [Emphasis added]

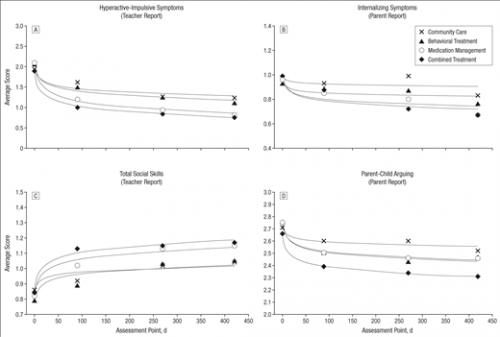

The study is the Multimodal Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA) study. It is among the best studies ever conducted in child psychiatry. Large samples of children diagnosed with ADHD were randomized into groups that received (a) the usual treatment offered in their community (‘Community Care’), (b) high-quality behavioral treatment, (c) medication following evidence-based guidelines, or (d) behavioral treatment and medication (‘Combined Treatment’). Community Care (a) might have included medication or behavioral treatment, but not the carefully-managed, evidence-based therapies delivered in conditions (b)-(d). Children were followed for 14 months. The Figure below presents the key results.

Statistical analyses showed that for most of these outcomes, behavioral treatment, medication, and combined treatment showed better results than community care. But although combined treatment was somewhat more successful than medication alone for some outcomes, those differences were not statistically reliable. The researchers concluded that

Combined behavioral intervention and stimulant medication—multimodal treatment, the current criterion standard for ADHD interventions—yielded no significantly greater benefits than medication management for core ADHD symptoms; this parallels findings reported by others.

The implication for practice was to medicate, medicate, and medicate. Medication is a much easier health service to deliver than behavioral treatment. Primary care physicians rarely have skills in behavioral treatment and even if they do they do not have the time that behavioral treatment requires. Similarly, it is much easier for a parent to give a child a pill than to change your behavior and your child’s. (Trust me on this: I raised five children.)

Yet several of the MTA authors are concerned that the study’s apparent validation of a “medication-only” strategy may have harmed children. They — and I — believe that even if there is a short term role for medication, children with ADHD symptoms need training to build the cognitive and social skills to function successfully without medication. Co-author Dr. Lily Hechtman:

I hope [the MTA] didn’t do irreparable damage. The people who pay the price in the end is the kids. That’s the biggest tragedy in all of this.

What went wrong?

It’s not that the MTA researchers were compromised by the pharmaceutical corporations. The study was conducted without drug company support. The constant promotion of medication by Big Pharma created a receptive environment for the message that “drugs are all you need,” but that’s not the authors’ fault.

The most important problem with the reception of the MTA findings was that we didn’t take a sufficiently developmental perspective in thinking about the problem. Learning to regulate your behavior and focus your attention are among the most important developmental tasks in childhood. A lot of this learning requires training by adults: This is much of what parenting and primary education are about. Some children need more help in this than others. Medication may be part of that help, but it is not a substitute for training. These developmental processes continue throughout childhood. This means that a 14-month study was not a sufficiently long period to draw definitive conclusions about the value of behavioral treatment or combined therapy.

ADHD has serious, long term effects on children. There hasn’t been nearly enough research on behavioral treatments for it; that has got to change. If you are parent and your child is taking an ADHD medication, I’m not recommending that you stop. But I do recommend that you find out what other treatment options may be available for you.

Disclosure: Like Aaron, I’ve published on ADHD. I am the statistician for a group seeking to developed an improved method to treat ADHD and I receive funding for this work. Several of the MTA investigators are my friends.