For a cheap Friday date-night, Veronica and I binge-watched the TV drama Chicago Med. It’s a fun, albeit cheesy Dick Wolf hospital drama—part soap opera, part surprisingly serious and earnest depiction of our urban ills. The show’s physical layout is apparently based on Rush University Medical Center.

Sometimes intentionally, sometimes not, such pop-culture fare reveals important information about what American society values, our blindspots and where our culture is headed–at least within the target demographics served by these shows.

Plotlines include a 14-year-old girl married to a 50-something sleazy preacher, myriad gunshot wound patients, a homeless pregnant youth who was also a victim of child abuse, patients with complicated lives facing serious cancers and other life-threatening conditions, families that require respite services and help paying huge medical bills.

One thing these plotlines didn’t include: Social workers. Leaving aside an insulting and grossly-stereotyped depiction of a welfare department caseworker who didn’t know the name of his patient, there’s no social worker in sight.

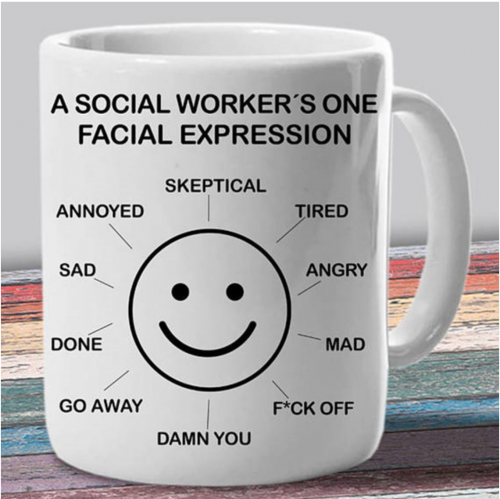

The social work craft is invisible on Chicago Med. It’s invisible on most television shows and most of our popular culture. When social workers are shown, they’re often depicted in cardboard ways: As naïve secular saints. Or as overworked, well-meaning, but incompetent bunglers. Or as malevolent bureaucrats who take children away.

(Friends on Twitter identified some notable exceptions, including the series Judging Amy, and the lovely little film Short Term 12.) That’s a terrible blindspot in our cultural understanding of medical and social care.

Within the real-life Rush University Medical Center, social workers would have been all over each of these plotlines. They’d actually be doing many tasks ostensibly performed by the main characters: Working with patients and families on end-of-life care, coordinating with social services, navigating paperwork snarls to obtain wheelchairs and other durable medical equipment, performing behavioral health assessments, and more.

The COVID pandemic shines a spotlight on the skill, dedication, and commitment of doctors, nurses, and the front-line public health workforce. That’s fantastic.

Less widely noted is the fact that many of these front-line workers are actually social workers and allied professionals.

- Who do you think are out there trying to secure housing and food for COVID patients so they can physically distance from loved-ones and others?

- Who do you think leads and manages homeless shelters, food pantries, and other social services?

- Who do you think serves individuals at-risk of behavioral crisis who might otherwise have violent encounters with first-responders?

- Then there are the outreach staff and nonprofit managers serving people who live with serious mental illness and substance use disorders, and others who assist individuals and families on matters of serious physical, mental, and developmental disabilities.

I myself am a public health researcher. I’m not a social worker, but I’ve spent the last eighteen years at the University of Chicago’s Crown School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice. I strongly identify with my colleagues in the social work profession.

So many of my amazing students, practitioner partners, and research colleagues are social workers—at the University of Chicago, in partner organizations such as Youth Guidance, NAMI, Thresholds, Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago Public Schools, and in other organizations.

My wife Veronica is a nurse-social worker. She’s a care coordinator at Lurie Children’s Hospital. Her patients face medical challenges from cancer to intellectual disabilities and eating disorders, alongside psychosocial challenges tranging from poverty and family dislocation, the need to coordinate complex educational and medical services, the need to secure durable medical equipment, the need to deal with Medicaid and other public assistance programs.

It’s a tough gig. The work of course requires altruism and dedication to patients. It requires more, too: Detailed knowledge of medical and social service systems, a thick Rolodex of bureaucratic contacts to get things done, cultural competence, resourcefulness, training, and grit.

COVID continues to be a brutal trial for so many social workers across the board. I’m proud of so many colleagues and friends, who have risen to this challenge. I feel for them and for many others who see so much, been through so much, endure constant issues of burnout and related challenges.

We in public health and in health care, loudly proclaim that American society must address the social determinants of health. yet we routinely overlook or denigrate social workers and allied professionals whose primary mission and training is precisely to address these determinants.

We must do better.