This post is coauthored by Austin Frakt, Aaron Carroll, and Steve Pizer.

On April 15 the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 2012 Budget Resolution. In doing so, it endorsed Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s “Path to Prosperity,” a long-term plan calling for major changes to Medicare and Medicaid; these changes dramatically reduce their funding. Under the plan, health care costs would be largely shifted to states (under Medicaid reforms) and individuals (under Medicare reforms), with predictable consequences of higher out-of-pocket costs, higher rates of un- and under-insurance, lower utilization of health care, worse health outcomes, and lower support for health care infrastructure.[1]

Another approach to reforming Medicare exists. By adequately funding the program, but in a smarter way, Medicare can save money without impoverishing its beneficiaries.

The House Plan

The House Budget Resolution envisions a new Medicare program, one that gradually ceases to serve its current function as a significant payer for health care. Beginning in 2022, traditional Medicare, which provides coverage to nearly 80% of beneficiaries today, would no longer be available to new enrollees. Instead, new enrollees would pay premiums to private plans, supplemented by an $8,000 government subsidy indexed to grow at the overall inflation rate. According to the Congressional Budget Office, beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket share of health spending would increase from about 25% under current law to 68% by the 2030.[2] With costs shifted to that extent, it is unlikely that beneficiaries – many with chronic conditions and significant health needs – could afford levels of care received today. Poorer health outcomes are a likely consequence.

The House’s plan is the latest salvo in a long political battle fought over the role of the private sector in Medicare. Though enrollment in private plans has grown in recent years, the program’s traditional, fee for service (FFS) arm remains overwhelmingly popular and well supported by the public and, historically, most policymakers.

The degree of participation and enrollment in private plans has historically been related to how generously those plans are paid. The House Budget Resolution would institutionalize a preference for private plans in a new way. Rather than enticing greater private plan enrollment with higher subsidies, as with Medicare Advantage now, it guarantees privatization by removing the public option, FFS Medicare. Meanwhile, support for coverage would erode so beneficiaries would bear more of the cost of care. This is a radical departure from Medicare as we know it, and also from the historical way of balancing the public and private arms of the program.

A Better Way

Two key changes to the House’s plan would better balance the interests and needs of beneficiaries, taxpayers, and others who provide and rely on health care. The first is to retain the traditional FFS arm of the program. Proposing to abandon it conflicts with its popularity while undermining the role it plays in supporting hospitals, physicians, and beneficiaries. FFS Medicare is accessible, familiar, and key to establishing and maintaining a standard minimum benefit. Although such a standard could be established without FFS, widespread understanding of it plays a role in supporting an adequate base of coverage for beneficiaries.

The second change is to reconsider how Medicare subsidizes plans, both public and private. Today, plans are funded at levels well above that which is required to provide the standard benefit. We know this directly from the plans themselves, which submit each year their expected actuarial cost of providing that benefit to an average beneficiary.

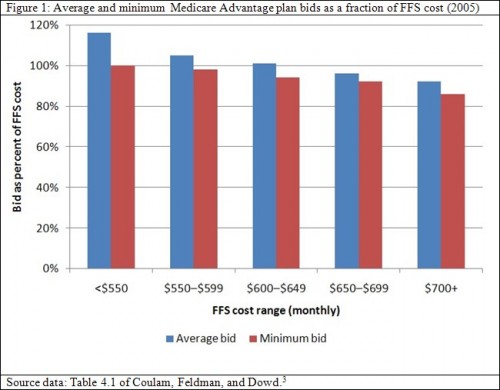

Figure 1 illustrates the average and lowest estimated plan cost, or “bid,” for provision of the standard Medicare benefit. These figures are shown as a proportion of FFS costs and stratified by per beneficiary, monthly FFS cost range, which varies across counties. In counties with FFS costs above $650, private plans could, on average, provide the Medicare benefit for less than FFS Medicare. Across all FFS cost ranges, at least one plan could do so, as reflected by the minimum bid. Yet payments to plans are not set according to the average or minimum costs as bid by the plans. They are set according to an administrative pricing system established by Congress. Consequently, payments to plans averaged 116% of FFS costs.[4] The health reform law passed last year reduces plan payments somewhat, but not below FFS costs, on average. Thus, there is plenty of room to economize without jeopardizing beneficiaries’ ability to enroll in a plan that covers the standard benefit.

One approach, termed “competitive bidding,” is to set government support to all plans, including FFS Medicare (which would also bid), at some function of bids. Setting it to the average bid would save about 4% of Medicare costs each year. Setting it to the minimum would save 8% (about $40 billion in 2009), but would leave as few as just one plan available to beneficiaries at no additional premium above the standard Part B premium.[5]

Competitive bidding is not new. Today, Medicare Part D subsidy levels are tied to the average bid for provision of the standard Medicare drug benefit. Additionally, voucher levels in insurance exchanges to be implemented under the new health reform law would be related to the second cheapest “silver” plan, which must cover 70% of the actuarial value of benefits.

By tying subsidy levels to bids that reflect the actual cost of care, they are guaranteed to keep pace with the price of health care services. In doing so, they afford crucial protection for beneficiaries. The House plan, by indexing them to overall inflation, provides no such protection. Thus, the House’s approach not only decimates FFS Medicare, but sets the stage for phasing out the entire program.

Medicare has been a critical component of the U.S. health system for 45 years. To be sure, it is in need of reform, as it is the principal source of projected increases in federal deficits. But Medicare does not exist in a vacuum. Its cost increases are reflective of system-wide increases and experienced by all payers, public and private alike. Attempting to solve Medicare’s problems by phasing out the program, as the House plan would, puts the burden of those costs where it can do the most damage, on a population most in need of health care. There are other ways; we can improve Medicare without impoverishing its beneficiaries.

References

[1] U.S. House Budget Committee. Path to Prosperity: Restoring America’s Promise. http://budget.house.gov/UploadedFiles/PathToProsperityFY2012.pdf.

[2] Congressional Budget Office. Long-Term Analysis of Budget Proposal by Chairman Ryan. April 5, 2011. http://web.archive.org/web/20120209062550/http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/121xx/doc12128/04-05-Ryan_Letter.pdf .

[3] Coulam RF, Feldman R, Dowd BE. Bring Market Prices to Medicare. AEI Press: Washington DC. 2009.

[4] Frakt AB, Pizer SD, Feldman, R. Payment Reduction and Medicare Private Fee-for-Service Plans. Health Care Financing Review. 2009;30(3):15-24.

[5] Coulam RF, Feldman R, Dowd BE. Bring Market Prices to Medicare. AEI Press: Washington DC. 2009.