The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2014, The New York Times Company).

Medicare Advantage plans — private plans that serve as alternatives to the traditional, public program for those that qualify for it — underperform traditional Medicare in one respect: They cost 6 percent more.

But they outperform traditional Medicare in another way: They offer higher quality. That’s according to research summarized recently by the Harvard health economists Joseph Newhouse and Thomas McGuire, and it raises a difficult question: Is the extra quality worth the extra cost?

It used to be easier to assess the value of Medicare Advantage. In the early 2000s,Medicare Advantage plans also cost taxpayers more than traditional Medicare. It also seemed that they provided poorer quality, making the case against Medicare Advantage easy. It was a bad deal.

At that time, Medicare beneficiaries could switch between a Medicare Advantage plan and traditional Medicare each month. (Now, beneficiaries are generally locked into choices for all or most of a year.) In that setting, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) found that relatively healthier beneficiaries were switching into Medicare Advantage and relatively sicker ones were switching out.

This suggested that Medicare Advantage didn’t provide the type of coverage or the access to services that unhealthier beneficiaries wanted or needed. Since the point of insurance is to pay for needed care when one is sick, it was tempting to condemn the program as having poor quality and failing to fulfill a basic requirement of coverage.

But things have changed. Mr. Newhouse and Mr. McGuire show, for example, that by 2006-2007, health differences between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and those in traditional Medicare had narrowed. About the same proportion of beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage as in traditional Medicare rated their health as fair or poor. This suggests that sicker beneficiaries were not switching out of Medicare Advantage and healthier ones were not switching in to the extent they had been in earlier years.

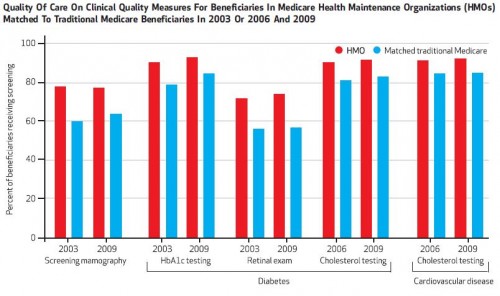

Also, in contrast to studies in the 1990s, more recent work finds that Medicare Advantage is superior to traditional Medicare on a variety of quality measures. For example, according to a paper in Health Affairs by John Ayanian and colleagues, women enrolled in a Medicare Advantage H.M.O. are more likely to receive mammography screenings; those with diabetes are more likely to receive blood sugar testing and retinal exams; and those with diabetes or cardiovascular disease are more likely to receive cholesterol testing.

That Health Affairs paper also found that H.M.O. enrollees are more likely to receive flu and pneumonia vaccinations and about as likely to rate their personal doctor and specialists highly.

There are reasons Medicare Advantage plans might promote higher-quality care. So long as beneficiaries don’t switch among plans too rapidly (and the evidence is that once they select a plan, they tend to stick with it), plans have a financial incentive to keep their enrollees healthy, incurring less downstream cost. It’s possible, therefore, that they may offer incentives to providers to perform preventive services.

Moreover, in contrast to traditional Medicare, which must reimburse any provider willing to see beneficiaries enrolled in the program, Medicare Advantage plans establish networks of providers. This permits them, if they choose, to disproportionately exclude lower-quality doctors, ones who do not provide preventive services frequently enough, for example.

Contemplating these more recent findings on quality alongside the higher taxpayer cost of Medicare Advantage plans invites some cognitive dissonance. On the one hand, we shouldn’t pay more than we need to in order to provide the Medicare benefit; we should demand that taxpayer-financed benefits be provided as efficiently as possible. Medicare Advantagedoesn’t look so good from this perspective.

On the other hand, we want Medicare beneficiaries — which we all hope to be someday, if we’re not already — to receive the highest quality of care. Here, as far as we know from research to date, Medicare Advantage shines, at least relative to traditional Medicare.

Is Medicare Advantage worth its extra cost? A decade ago when quality appeared poor, the answer was easy: No. Today one must think harder and weigh costs against program benefits, including its higher quality. The research base is still too thin to provide an objective answer. Mr. Newhouse and Mr. McGuire hedge but lean favorably toward Medicare Advantage, saying cuts in its “plan payments may be shortsighted.”

***

Here’s a bonus chart, not provided in the original post, of some of the quality measure results described in the post.