This post is part of a multi-post series on the filibuster in the U.S. Senate. An index to all other posts in the series, as well as a list of main sources that have informed this series, is included in the first post.

In this installment I summarize the history of the filibuster.

Sarah Binder, author of Politics or Principle: Filibustering in the United States Senate, explained in a March 2010 interview with Ezra Klein that the origins of the Senate’s filibuster stem from the removal of the “previous question motion.” I hate the name of that motion since it reveals to me little of its function. It suffices to know that it is essentially a simple majority version of today’s 60-vote cloture rule. That is, a previous question rule would terminate debate in the Senate with 51 votes. Binder to Klein:

In 1805, Aaron Burr … comes back to the Senate and gives his farewell address [in which] he goes through the rulebook pointing out duplicates and things that are unclear.

Among his suggestions was to drop the previous question motion. And they pretty much just take Burr’s advice. And once it’s gone, it takes some time for leaders to realize that they can’t cut off debate anymore. But the striking part to me was that we say the Senate developed the filibuster to protect minorities and the right to debate. That’s hogwash! It’s a mistake. Believe me, I would’ve loved to find the smoking gun where the Senate decides to create a deliberative body. But it takes years before anyone figures out that the filibuster has just been created.

Thus, the filibuster was not invented in a conscious effort to create a more deliberative legislative body. It was, rather, an accidental byproduct of early 19th century Senate rules reform. The Senate’s filibuster owes its existence not to design but to a lack of provisions that would limit senators’ rights to participate in the legislative process.

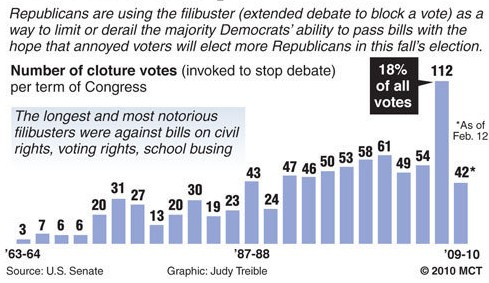

Though it has existed for centuries, the filibuster’s form and frequency have not been constant. Filibustering was rare before 1960 and “has skyrocketed since then, from an annual average of 3.2 filibusters during 1951–1960 to 16.5 between 1981 and 2004. … [There were] 111 during the 110th Congress (2007-2008) alone.” (Source: Koger.) The following figure documents the number of filibuster-ending cloture votes by year (Source: David Lightman, McLatchy).

Scholars have investigated the extent to which changes in rates of filibuster are correlated with other seemingly relevant factors like Senate turnover, partisanship, and threat of reform. These factors, however, do not have a strong relationship with filibuster use historically.

The frequency of filibuster has increased as the legislative penalties for obstruction have decreased. Prior to 1917 the only available responses to the filibuster were to wait it out or to strike a deal. In 1917, Woodrow Wilson convinced the Senate to adopt a rule that could limit debate, the cloture rule. In its original form it allowed for the halting of debate if two-thirds (not today’s three-fifths) of senators agreed.

Though a cloture rule existed, it wasn’t frequently used until much later in the century. The change came after the strategy of trying to outlast a filibuster failed during debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1960. Southern senators thwarted efforts to bring debate to a close.

This failure led several senators to rethink the Senate’s tolerance for filibustering, given the body’s growing workload. After all, the federal government had expanded tremendously since the 1930s, and the United States had taken on the foreign-policy responsibilities of a world superpower. Moreover, with the growing availability and convenience of air travel, senators also enjoyed easier transportation to their home states, to speaking opportunities around the country, and to foreign travel. It was increasingly difficult for the legislature either to overcome or outlast a filibuster. (Source: Koger.)

Consequently, the necessity of cloture votes to pass major legislation become routine. In 1975, Nelson Rockefeller, Gerald Ford’s Vice President, succeeded in a decades-long effort to reduce the cloture threshold. It dropped from a two-thirds to a three-fifths majority, the level that exists today. Around the same time filibustering shifted from a round-the-clock talk-a-thon that shut down the Senate to a behind the scenes threat that blocked individual bills (“holds”). A further shift in filibuster tactics and frequency was facilitated by Robert Byrd’s dual-track system, which put filibustered legislation to the side so the Senate could take up other business. Forcing a cloture vote no longer gummed up the entire Senate. It just slowed down or blocked passage of a specific piece of legislation.

The rules governing cloture have been modified over time in other ways. For example, before 1979 there was no cap on the time allotted for post-cloture debate, opening the possibility for post-cloture filibuster (a seeming oxymoron that was exploited). Thus, in 1979 debate was capped at 100 hours after a successful cloture vote. In 1985 the cap was reduced to 30 hours. However, even that length of debate had never occurred as of the writing of a 2003 Congressional Research Service report on the issue. Since 2003, 30 hours of post-cloture debate have been used, most recently during the debate over health reform in December 2009.

Today forcing cloture votes has become a standard tactic of the minority, even when it doesn’t have the votes to sustain a filibuster. Ezra Klein explained the rationale in a March 15, 2010 Newsweek column.

The goal is to slow the Senate to a crawl. After you call for cloture, you need to wait two days to take the vote. After you take the vote, there’s 30 hours of post-cloture debate. And you can do this on the motion to debate, on amendments, on the vote on the bill itself … on everything, really. A single, committed crank … can waste weeks forcing the majority to break his filibusters.

With these innovations of obstruction, filibustering became less costly to the minority. It was less public and did not threaten other Senate business. Thus, it became a more routine means by which to extract concessions. Welcome to the modern Senate, the home of gridlock.