TIE readers know about Anne Case and Angus Deaton’s paper reporting that middle-aged white Americans are dying at an accelerated rate (if not, follow the link or read Austin). There’s currently a nifty debate about the statistical underpinnings of Case and Deaton’s estimates (see Andrew Gelman and Deaton’s reply).*

But there’s an important point being missed. We’re not doing much about the causes of mortality that Case and Deaton highlight.

Case and Deaton found that

three causes of death… account for the [increase in] mortality… among white non-Hispanics, namely suicide, drug and alcohol poisoning (accidental and intent undetermined), and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis.

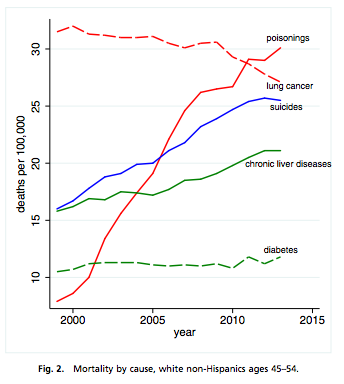

They illustrate the increases in these causes in this Figure:

Case and Deaton believe that the increases in suicide, substance abuse, and liver disease are related to a concurrent epidemic of pain (Richard Friedman argues that misuse of opioids in pain control is an important part of the explanation).

In looking at these death rates, think about not just the suffering of the victims preceding these deaths, but also about what their families went through, before and after the deaths. Moreover, if 30 poisonings / 100,000 people doesn’t sound like a lot, consider that

for each prescription painkiller death in 2008, there were 10 treatment admissions for abuse, 32 emergency department visits for misuse or abuse, 130 people who were abusers or dependent, and 825 nonmedical users.

Similarly, the CDC reported about 30 suicide attempts for each completed suicide in 2013.

Case and Deaton claim that the increased mortality among middle-aged whites is comparable to the total mortality of AIDS:

If the white mortality rate for ages 45−54 had held at their 1998 value, 96,000 deaths would have been avoided from 1999–2013, 7,000 in 2013 alone. If it had continued to decline at its previous (1979‒1998) rate, half a million deaths would have been avoided in the period 1999‒2013, comparable to lives lost in the US AIDS epidemic through mid-2015.

These specific numbers will likely be revised as the data are studied further. Nevertheless, suicide, substance abuse, chronic pain, and alcohol-associated liver disease are enormous public health problems, and they are getting worse for a large component of the population.

So what are we doing about this? As was the case for HIV infection early in the AIDS epidemic, we need a better understanding of the social determinants of these problems and we need much better treatments. America made a large investment in AIDS research, chiefly through the NIH, and achieved both of these goals.

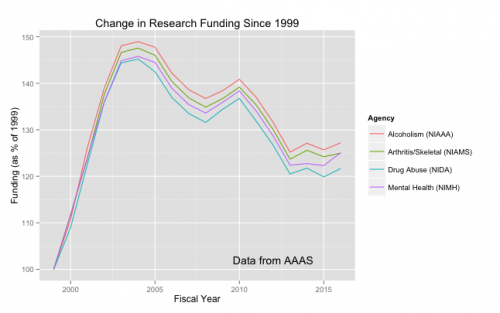

But look at the history of NIH funding since 1999 in the institutes most relevant to these problems.

Using data from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, I’ve graphed funding for the NIH Institutes concerned with Mental Health (NIMH), Alcoholism (NIAAA), Drug Abuse (NIDA), and Arthritis and Musculo-Skeletal Diseases (NIAMS, because much pain treatment is associated with these diseases). I took the constant-dollar funding for each year and expressed it as a percentage of the institute’s funding in fiscal year 1999.

Here’s the key point: We’re losing many lives to suicide, alcohol, drug abuse, and chronic pain. Since about 2004, we’ve been spending less trying to understand why it’s happening and how we can treat it. As Aaron argues here, there are societies that have turned the corner on problems like suicide. There is no excuse for despair.

*It’s a tangent, but this debate illustrates how electronic media benefit science. If the back and forth between Gelman and Deaton had been confined to academic journals, as it would have been just a few years ago, it would have unfolded over months or years. On blogs and twitter, there’s been real progress in just days. Aaron discussed whether such a provocative paper ought to have appeared in one of the premier medical journals. That may not matter as much as it used to.