I just can’t believe we’re still talking about raising the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 67.

I’ve written so much about what’s wrong with this policy, that I hesitate to do so again. But when faced with the realization that much of what I said still hasn’t permeated the general thinking of policymakers in Washington, I believe that we could make another go at this. Let’s start with life expectancy.

Almost all of the arguments for raising the eligibility age coalesce around the idea that since life expectancy has gone up so much, we have to think about making people work a little longer. If a person really is going to live fifteen years or more than they used to, it only makes sense to ask them to work an extra year or two before retiring, no?

Life expectancy at birth has gone up quite a bit since the 1950’s when Social Security was young. But since we’re talking about Medicare, it makes more sense to talk about how much it’s gone up since 1965. It’s still increased since then, about 8-9 years in fact. Perhaps that might seem enough to ask people to work longer.

But hold on a minute – that’s life expectancy at birth. That’s affected by many things, including babies who die in childbirth and diseases that used to prevent children from becoming adults. That’s not what affects Medicare. In fact, as horrible as this is to say, a person who lives to 64 and then dies is a boon to the Medicare budget. They’ve contributed many, many years of Medicare taxes and never drawn a dime from the program.

What we really care about when we talk about how much Medicare costs is life expectancy at age 65. The meaningful question is, if you make it to 65, how many more years will you live? That’s how many years you could expect to be on Medicare, and that’s how much you could cost the rest of us.

In 1965, the life expectancy at age 65 was somewhere between 14.5 and 15 years. In other words, if you made it to 65, even in 1965, you could expect to live to about 80. That’s much older than you’d think given the rhetoric of today. In 2009, it was 19.2 years, meaning if you made it to 65, you could expect to live until you were just over 84. Think about that for a minute. People are actually living on average less than 5 years longer today on Medicare than when the program was passed.

But maybe you still think that is a significant difference. People are living in retirement, after all, five years more than they used to. Perhaps you still think that it makes sense to ask them to work two more years.

For that to be true, however, you have to believe that everyone is living five more years. After all, if it turned out that many people were living only one more year than they used to, then it wouldn’t make sense to raise the age of eligibility two years, would it? You’d be effectively giving them less Medicare than they got when the program was enacted.

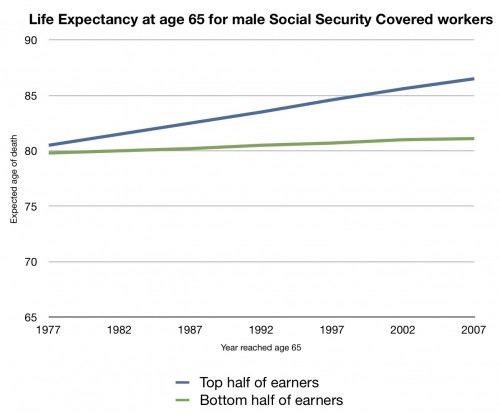

Well, take a look at this again:

What you’re seeing is life expectancy at age 65 broken out in to the top half of earners and the bottom half of earners, from 1977 to 2007. I got these data from a study that appeared in Social Security Bulletin in 2007. The paper was entitled, “Trends in Mortality Differentials and Life Expectancy for Male Social Security–Covered Workers, by Socioeconomic Status.” We know that average life expectancy went up less than 5 years overall in this period. But what’s somewhat stunning is how much of a disparity there is in these gains. The top half of earners gained more than 5 years of life at age 65. The bottom half of earners, though, gained less than a year.

If you raise the age of eligibility by two years, then you are taking away more years of Medicare than half the country gained in longer life. Moreover, we’ve already taken away these people’s Social Security. The Greenspan Commission in the early 1980s made it so that the retirement age is already 66. It’s scheduled to rise to 67. So those at the bottom half of the socioeconomic ladder have already lost more years of Social Security than they’ve gained in years of life life expectancy at 65.

Sure, in a perfect world poor young seniors could get Medicaid if we take away their Medicare. That is, of course, if their state accepts the Medicaid expansion. Many haven’t. Less poor young seniors can go to the exchanges, I suppose. But if you’re a 65 year old widow and you make $46,100 a year in a high cost area, then your premium will be over $12,000 for your insurance. And you could owe another $6250 in out-of-pocket costs if you get sick. Tell me again how that person won’t miss her Medicare.

Another important point: there’s an argument to be made that people in the bottom half of earners probably have jobs that are more strenuous than those in the top half of earners. My job requires me to sit at a desk and type. I’m lucky enough to be in the top half of earners, and I should be able to do this job far past age 65. Others have to do manual labor, or activities that become more difficult as they age. It’s likely that people age 66 who are in the bottom half of earners will have a harder time continuing to work than those in the top half. Asking them to work longer may be impossible.

And I haven’t even discussed how doing might hurt people’s health. Did I mention that it costs us more than it saves? Why are we considering this again?

About the only reason I’ve heard for doing this that was logically consistent is that it might be used as a bargaining chip to get other things we want. If we’re going that route (which I don’t like), at least let’s acknowledge that this policy isn’t harmless. It will have real consequences for real people.