From a public spending point of view, post-acute care is particularly problematic. Most of Medicare’s geographic spending variation is due to this type of care. Part of the story is that Medicare pays for post-acute care in several different ways, with different implications for efficiency.

For example, traditional Medicare (TM) — which spends ten percent of its total on post-acute care — pays skilled nursing facilities per diem rates but inpatient rehabilitation facilities a single payment per discharge. Post-acute care is also available through Medicare Advantage (MA), which operates under a global, per-enrollee, payment. Unlike TM, MA plans establish networks, may require prior authorization for post-acute care, and can charge more in cost-sharing for post-acute care than TM does.

These different payment models offer different incentives that may affect who receives care, in what setting, and for how long. In Health Affairs, Peter Huckfeldt, José Escarce, Brendan Rabideau, Pinar Karaca-Mandic, and Neeraj Sood assessed some of the consequences of those incentives. Focusing on hospital discharges for lower extremity joint replacement, stroke, and heart failure patients between January 2011 and June 2013, they examined subsequent admissions to skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation facilities, comparing admission rates, lengths of stays, hospital readmission rates, time spent in the community, and mortality for MA and TM enrollees. To do so, they used CMS data on post-acute patient assessments for patients with discharges from hospitals that received disproportionate share or medical education payments from Medicare.

You might be wondering how the investigators could possibly study MA patients with CMS data. First of all, post-acute facilities are required to file patient assessments for all patients, MA and TM alike. Second, in order to pay disproportionate share and medical education payments to hospitals, CMS collects “information only” (i.e., zero charge) claims for MA patients from hospitals entitled to those payments. Such hospitals account for 92 percent of Medicare discharges. (As far as I know, validation analyses of information only claims has not been published.)

Their analytic file included almost one million lower extremity joint replacement episodes, almost a half-million stroke episodes, and just over three-quarters of a million heart failure episodes. About a quarter of these were for MA patients. Their analyses adjusted for patient characteristics and used hospital fixed effects.

Lower extremity joint replacement MA patents were two percentage points more likely to be admitted to a skilled nursing facility than TM patients, but an MA patient stayed 3.2 fewer days, on average. On the other hand, lower extremity joint replacement MA patients were far less likely to be admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility than TM patients — an adjusted difference of 6.4 percentage points. Lengths of stay were about the same.

Findings for stroke patients were similar. TM heart failure patients were slightly more likely to be admitted to a skilled nursing facility than MA patients, and stayed 1.7 days longer than MA patients. The trend is similar for heart failure patient admissions and stays at inpatient rehabilitation facilities, but the overall rates of admission to them is very low for these patients.

MA patients of all types were less likely to be readmitted to the hospital and more likely to be living in the community than TM patients. There were no statistically significant mortality differences. These results suggest that MA patients are not adversely affected by their lower volume of post-acute care utilization.

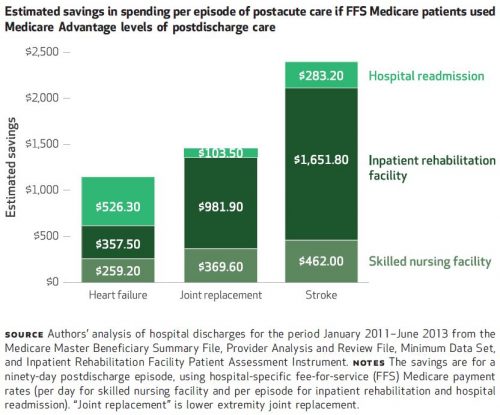

If TM patients were to somehow adopt the same level of utilization of post-acute care as MA patients, the program would save money. Results of the authors’ savings calculations, by condition, are shown in the following chart. Overall, they represent about a 16 percent reduction in spending.

One way TM is progressing toward more efficient post-acute spending is through accountable care organizations (ACOs). That’s according to a recent paper by J. Michael McWilliams and colleagues. They found, for example, that ACOs that entered the Medicare Shared Savings Program in 2012 reduced post-acute spending by 9% without reductions in quality of care (as measured by mortality, readmissions, and use of highly rated skilled nursing facilities), relative to non-ACO providers.

Naturally, there are some limitations to the Huckfeldt et al. analysis. First, though the authors did not detect any favorable selection into MA, it is possible that MA patients differ systematically from TM patients such that the results are not completely driven by MA care management. Second, the study did not examine every type of post-acute care — home health care, long-term hospital care, or other outpatient care were omitted from the analysis. Home health care is less costly than the types of care examined. Long-term hospital care is relatively rare. And, outpatient care is unobservable for MA. Third, there are other, possible measures of quality of care besides those examined (readmissions, time in the community, and mortality).

All told, the results suggest that MA manages post-acute care more tightly than TM and with no observed, negative consequences for patients.