On May 5, physician organizations made some doc fix suggestions to Congress. Some seem sensible. Others raise concerns. First, let’s review the fundamentals.

According to current law physician payments under Medicare Part B will be cut by nearly 30% as of January 1, 2012. To make a long very story much shorter, that’s due to a payment update mechanism known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) and the fact that Congress has rarely allowed SGR-mandated cuts to go into effect, kicking the can down the road so many times that the cumulative result is to require that huge cut at the turn of the year. Few think that massive SGR cut will be allowed to happen, but there is no agreement on what should replace it, i.e., a “doc fix.”

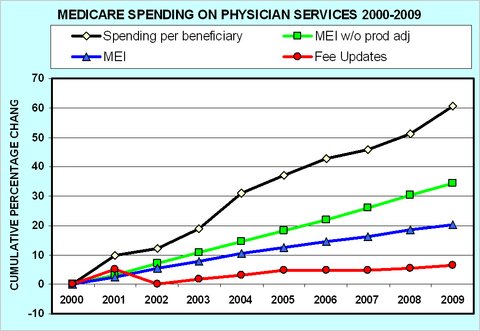

Interestingly, over the last decade, fights over and resolutions of interim doc fixes have kept Medicare Part B payments growing at a modest rate, as the following chart from Uwe Reinhardt shows (red line). Nevertheless, actual per beneficiary spending has grown considerably (black line). Therein lies the problem. Neither the SGR nor the “fixes” have actually fixed anything. (For more on this graph and the other two lines, blue and green, that I didn’t mention, see this prior post.)

Clearly, if we have a spending growth problem and it is not to be found in fee updates then it must be in utilization. After all, total spending is the sum across services of prices times volumes (or, simplified to a single service, price times quantity). So, it’s those service volumes that are a problem. They’re out of control. That’s because the current fee-for-service regime has incentives for greater utilization. The more physicians supply, the more revenue they earn.

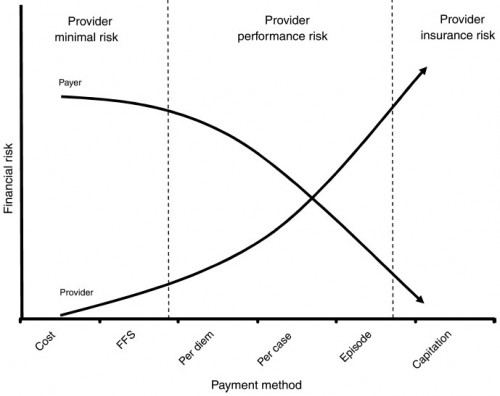

Any true doc fix would have to address that incentive. Various flavors of capitation and bundling would do so, essentially paying for a larger basket of care rather than procedure-by-procedure, as the program currently does. Physician groups suggested as much in their proposals to Congress. That’s sensible because bundling and capitation have incentives for lower volume. Paid a fixed amount for a set of services or a period of time, if providers can shave costs (while meeting quality benchmarks) they pocket more profit. That’s the 30,000 feet view. Naturally, the devil is in the details.

As the foregoing explanation should make clear, moving from fee-for-service-based payment to various forms of capitation shifts the financial risk from Medicare (taxpayers) to providers. This is illustrated in the following figure from Averill, et al. (JACM, 2010). Naturally, physicians will be concerned about taking on financial risk, and I would expect they would seek as much protection from Congress as they can negotiate in any final doc fix bill, should we ever see one.

Physician groups requested something else of Congress too: the right to enter into “private contracting,” another term for balance billing, or charging Medicare beneficiaries the balance of fees not covered by Medicare. Currently, that is not permitted by the program, unless a physician rejects all Medicare payment. Some argue that balance billing could actually decrease beneficiary out-of-pocket cost since physicians must currently charge the full 20% Part B cost sharing. I don’t buy that argument in the aggregate. If physicians were willing to take less money in general, we wouldn’t have had regular debates over Medicare’s physician fees in the first place.

It is far more likely physicians wish to be paid more. Heck, I would! Therefore, private contracting is likely to be result in cost shifting. Beneficiaries would be charged higher cost sharing as Medicare’s fees failed to keep up with whatever physicians wished to charge and the market could bear. In this sense, it is not too different in spirit from Rep. Ryan’s plan for Medicare: save taxpayer money by putting the burden on beneficiaries. That’s likely to be politically problematic and isn’t necessarily the right thing to do for beneficiary health or financial protection either.

In this process, we have already seen one benefit of the SGR. It motivates stakeholders to think creatively about alternatives to the status quo. For this reason, Congress should be careful how it proceeds. If a doc fix is implemented that removes the SGR it may also remove incentives to come to the bargaining table. However, if it also fails to fully remedy Medicare Part B’s spending problem, a future Congress may regret the deal struck.

The SGR is flawed in every way but one. It is a substantial political bargaining chip. On behalf of taxpayers, it ought not be traded away casually. Bruce Bartlett has argued that it should not be traded away at all, but that the SGR savings — all of it — be used to secure a debt ceiling deal. Whatever is done about the SGR, let’s just make sure the doc fix cure isn’t worse than the disease.