This post was coauthored by Austin Frakt (@afrakt) and Sarah Gordon (@SarahHallGordon), an assistant professor with the Department of Health Law, Policy & Management at Boston University.

On January 30, 2020, the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) released a National Vital Statistics Report describing changes to maternal mortality coding and reporting. The report also documents a bit of the history in measuring maternal mortality and data limitations. This post summarizes some of the history and data limitations and documents other sources of maternal mortality statistics.

Since 1915, official maternal mortality statistics have come from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS). Based on death certificates, it uses the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of maternal deaths:

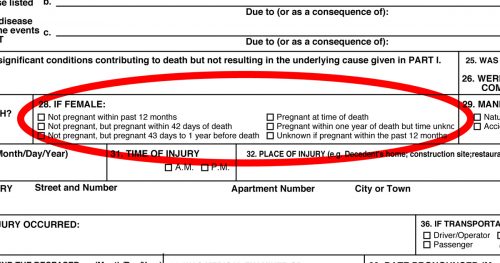

deaths of women while pregnant or within 42 days of being pregnant, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

The report notes that other data collection efforts considered more accurate showed that the NVSS-derived maternal mortality rate was an underestimate. Therefore, as states transitioned to a new death certificate form that included maternal death-related checkboxes, from 2007-2018, NCHS did not publish official maternal mortality statistics.

This data collection change itself affected mortality statistics:

When combining data for all states where the number of states adopting the checkbox increased differentially over time, the observed trend in maternal mortality appears to indicate an increase. However, it has been shown that this is mainly a reflection of the states’ incremental implementation of the checkbox over a 14-year period.

Because relying on the checkbox alone leads to over-reporting of maternal deaths due to checkbox errors, NCHS made some other changes (detailed here) to how it uses death certificate data in coding maternal mortality, effective for the 2019 reporting year (of 2018 data). The NCHS 2018 maternal mortality rate estimate is 17.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. The rate is 37.1 deaths per 100,000 for black women, 14.7 for white women, and 11.8 for Hispanic women. In light of the aforementioned data collection changes, it is reasonable to be skeptical of claims that these represent increases in death rates from prior years or, if they do, just how big the increases are.

Julia Belluz at Vox reports that the overall 2018 U.S. figure puts the U.S. 55th in the world (meaning 54 countries have lower maternal mortality rates) and last among the 10 of the wealthiest countries. But, again, given the challenges in collecting and correcting maternal mortality data, both in the U.S. and in other countries, it is reasonable to wonder how accurate these rankings are.

There are other data to go on, though unfortunately some of it may inherit NVSS’s challenges and the best data we have is not geographically comprehensive.

In 1986, the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS) was developed. A paper in Obstetrics & Gynecology explains that this system supplements maternal death records with links to birth and fetal death certificates and other public sources. Cases are reviewed by clinicians. PMSS considers a death a pregnancy-related mortality if it is within one year of pregnancy and is from a cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.

PMSS data are held confidentially by the CDC and not available to researchers. However, aggregate statistics from PMSS are released. Here, for example, is a time series of pregnancy-related mortality based on the PMSS. As the PMSS relies on the NVSS as a starting point, it could also be influenced by the change in data collection methods over time, and concerns about the data are acknowledged by the CDC. For that reason, we’re not reproducing the time series or citing figures from it here.

Another paper in Obstetrics & Gynecology describes a third maternal mortality data collection effort. Beginning in 1930 in New York and Philadelphia and subsequently spreading to other areas of the country, maternal mortality review committees sought to overcome some limitations of death record-only approaches. In particular, such committees conducted case reviews to assess what may have caused maternal deaths, with an aim of reducing them. In fact, they were not created to establish an accurate count of maternal deaths, but rather to make recommendations to reduce maternal mortality.

All but a few states have a maternal mortality review committee today. They are considered the most accurate source of maternal mortality data, but there are no public trend estimates produced from them. The CDC has analyzed data from 14 state review committees and concluded, among other things that two-thirds of maternal deaths are preventable. The CDC has not used these data to report a maternal mortality rate or trend.

Though the data are not reliable enough to determine whether maternal mortality has increased over time, it is safe to say that the U.S. has a higher maternal mortality rate than it should and there are some concerning racial disparities in maternal outcomes.