In an ideal health care system, you’d get the same (very good) care whether you were admitted to a hospital on a Monday, Wednesday, Friday, or Sunday. We don’t have an ideal health care system, and it turns out that day of admission matters. A new paper by Ann Bartel, Carri Chan, and Song-Hee Kim illustrates this fact, and then exploits it as an instrumental variable (IV) in an analysis of mortality and hospital readmissions.

Prior work by Varnava et al. (2002) and Wong et al. (2009) showed that hospitals would rather not keep patients over the weekend if they can discharge them on a Friday. Examining three hospitals in the UK, Varnava et al. found that discharges were most common on Fridays. Considering a hospital in Toronto, Wong et al. found that “[w]eekend discharge rate was more than 50% lower compared with reference rates whereas Friday rates were 24% higher. Holiday Monday discharge rates were 65% lower than regular Mondays, with an increase in pre-holiday discharge rates.”

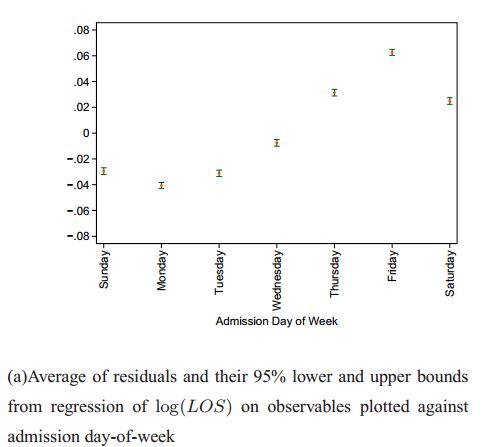

Bartel, Chan, and Kim found something similar among US Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure (HF), pneumonia (PNE), or acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in 2008-2011. The following chart from their paper plots the logarithm of length-of-stay (LOS) versus admission day-of-week for HF patients, controlling for age, gender, race, comorbidities, receipt of surgery, enrollment in Medicare Advantage, seasonality, and hospital fixed effects. (That’s why the figure’s caption calls this a “residual.”) As shown, HF patients admitted on Sunday-Tuesday have shorter lengths of stay than those admitted on a Wednesday-Saturday. A similar pattern exists for PNE and AMI patients.

Why? The hypothesis is that there is an incentive to get patients out of the hospital before the weekend, unless it’s pretty clear they’ll need to stay through the weekend. This could be due to patient demand (e.g., they want, or their family wants them, to be home on weekends). Or it could be due to provider factors (e.g., less staff on the weekend makes it harder for the hospital to provide care or plan discharges). Also, under diagnosis-based payment that Medicare uses, staying an extra day that could be avoided is all cost for no additional revenue.

Whatever the reason if the admission day is random with respect to outcomes, it could be a good instrument, a way to estimate a causal relationship between length of stay and things like mortality or hospital readmissions. If admission day is a good instrument, stratifying by it should balance observable factors, like comorbidities. If, for example, patients admitted earlier in the week are also sicker, then their outcomes could be worse not because they are discharged earlier (before the weekend) but because of their more severe illnesses, invalidating the instrument.

In principle it isn’t absolutely necessary that observable factors like comorbidities be balanced across values of the instrument, because they can be controlled for. However if there is not balance across instrument strata among observable factors, it should reduce our confidence that there is balance among unobservable factors, which is the key hypothesis for IV. So, checking balance on observables, like comorbidities, is a falsification test, something every IV study should include. (If one’s theory suggests that there ought not be balance on some, specific observables, then we might forgive that, and the analysis should control for them. But there must be some observables for which balance occurs or else why should we believe it does so for all unobservables correlated with outcomes?)

This falsification test is a direct analog of the typical “Table 1” in a publication of results from an RCT. A standard table 1 shows balance of observable factors across treatment/control arms. If you ever saw an unbalanced Table 1, you’d suspect a breakdown in the randomization. The study would be fatally flawed. Well, one can and should do this type of test with IV too.

Considering HF patients, Bartel, Chan, and Kim do find balance of comorbidities when stratified by Sunday/Monday admissions versus admissions on any other day, but only for those with greater severity of disease. The reason could be that day of admission is more random for high severity patients; they may have less control over when they enter the hospital than other, less severely ill patients, the relatively sicker* of whom seem disproportionately to be admitted on Sundays and Mondays. Therefore, their instrument is probably not valid for less severe HF patients. A similar falsification test did not reject the validity of the instrument for the AMI and PNE study cohorts.

Main lesson: Do falsification tests. Adjust analysis accordingly.

The paper’s principal results are as follows:

- “For HF patients with high severity, one more hospital day decreases readmission risk by 7%. This relationship between LOS and readmissions does not exist for PNE or AMI patients, but we show that longer LOS can reduce their mortality risks by 22% and 7% respectively.”

- “Keeping all FFS [Medicare fee for service] PNE patients in the hospital for one more day would save 19,063 lives [over four years].”

- “Keeping all FFS AMI patients in the hospital for one more day saves 2,577 lives [over four years].”

These results suggest that discharges to avoid weekends and that shorten LOS harm patients, as does shorter LOS in general (at the margin examined). However, we should only believe them to the extent we believe the instrument. The falsification tests in the paper should increase our confidence in the validity of findings.

* To help you parse this: I’m talking about the relatively sicker among the less severely ill subset. This is bloggerrifically vague, but details are in the paper.