The following is a slightly edited excerpt from the working paper version of my paper “How much do hospitals cost shift? A review of the evidence,” to appear in issue 1, volume 89 of The Milbank Quarterly (expected March 2011). See also “Estimating Hospital Cost Shift Rates:A Practitioners’ Guide“. This post has been cited in the 3 February 2011 edition of Health Wonk Review.

It is well-known that hospitals charge different payers (health plans and government programs) different amounts for the same service even at the same point in time, a phenomenon known to economists as “price discrimination” (Reinhardt 2006). It is also widely believed that hospitals charge more to one payer because it received less (relative to costs or trend) from another, a dynamic, causal process I’ll call “cost shifting,” following Morrisey (1993, 1994, 1996) and Ginsburg (2003), among others.

Price discrimination and cost shifting are related but different notions. The first depends on differences in market power, the ability to profitably charge one payer more than another but with no causal connection between the two prices charged. In the second, there is a direct connection between prices charged. In cost shifting, if one payer pays less relative to costs (Medicare, say), another necessarily pays more (a private insurer, say). Cost shifting implies price discrimination but the existence of price discrimination does not imply cost shifting has occurred or, if it has, at what rate (i.e. how much did one payer’s price change relative to that paid by another).

Cost shifting concerns have played a role in consideration of hospital payment policy for decades. According to Starr (1982), in the 1970s “commercial insurance companies worried that if the government tried to solve its fiscal problems simply by tightening up cost-based reimbursement, the hospitals might simply shift the costs to patients who pay charges.”

A 1992 report by the Medicare Prospective Payment Assessment Commission (ProPAC) asserted that hospitals could recoup underpayments by Medicare from private payers (ProPAC 1992). Were that so, hospitals would need not need to fear inadequate government payments. Yet, somewhat paradoxically, around the same time hospitals used the cost shifting argument to call for higher public payment rates (AHA 1989).

More recently, during the debate preceding passage of the new health reform law—the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—two insurance and hospital industry-funded studies (PWC 2009, Fox and Pickering 2008) and one peer-reviewed publication (Dobson et al. 2009) reasserted a high degree of cost shifting to private payers stemming from public payment shortfalls. Half to all of shortfalls were assumed to be shifted to private payers.

The cost shifting issue is certain to arise again in the near future. Though cost shifting was debated during consideration of the ACA, public payment policy is not settled, nor will it ever be. The new health reform law includes many provisions that are designed to reduce the rate of growth of public sector health care spending. For instance, the law’s provisions will reduce annual updates in payments for Medicare hospital services, pay for them in part based on performance on quality measures, lower payments for preventable hospital readmissions and hospital-acquired infections, among others (Kaiser Family Foundation 2010, Davis et al 2010). In aggregate and over the ten-year period 2010-2019, the CBO scored the savings from reduced Medicare hospital payments at $113 billion (CBO 2010b).

Additionally, Medicaid eligibility will expand in 2014 to all individuals with incomes below 133% of the federal poverty level. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that by 2019 Medicaid enrollment will grow by 16 million individuals (CBO 2010a). To the extent that some of these new Medicaid beneficiaries would have otherwise been covered by private plans (a crowd-out effect; Pizer, Frakt, and Iezzoni 2010), lower Medicaid payments relative to private rates may increase incentives to shift costs. On the other hand, to the extent that Medicaid expansion, as well as the equally large (CBO 2010a) expansion of private coverage encouraged by the ACA’s individual mandate and insurance market reforms, decrease rates of uninsurance and uncompensated care, the law may decrease hospitals’ need to shift costs. Nevertheless, if past experience is any guide, as some of ACA’s provisions are implemented, they are likely to be challenged with cost shifting arguments by the hospital and insurance industries.

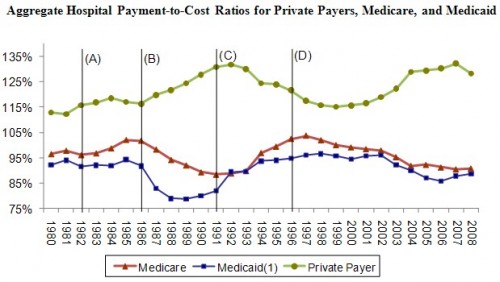

In tomorrow’s post, I will review discuss the descriptive evidence that is often pointed to as the signature of cost shifting: time series of aggregate hospital payment-to-cost ratios by payer (below). Does this figure illustrate cost shifting? It’s not a simple question.

Figure sources: AHA (2003, 2010).

References

AHA (American Hospital Association). 1989. CEO Answers Letter Charging Medicare Rip-Off by Hospitals. AHA News. 20 February.

AHA (American Hospital Association). 2003. Trendwatch Chartbook 2003: Trends Affecting Hospitals and Health Systems.

AHA (American Hospital Association). 2010. Trendwatch Chartbook 2010: Trends Affecting Hospitals and Health Systems.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2010a. H.R. 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Final Health Care Legislation).

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2010b. Distribution Among Types of Providers of Savings from the Changes to Updates in Section 1105 of Reconciliation Legislation and Sections 3401 and 3131 of H.R. 3590 as Passed by the Senate. http://web.archive.org/web/20120118172940/http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11379/Distribution.pdf , accessed 16 November 2010.

Davis P, Hahn J, Morgan P, Stone J, Tilson S. (2010). Medicare Provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA): Summary and Timeline. Congressional Research Service.November 3.

Dobson A, DaVanzo J, El-Gamil A, and Berger G. 2009. How A New ‘Public Plan’ Could Affect Hospitals’ Finances and Private Insurance Premiums. Health Affairs. 15 September.

Fox W, Pickering J. 2008. Hospital & Physician Cost Shift: Payment Level Comparison of Medicare, Medicaid, and Commercial Payers. Milliman. December.

Ginsburg P. 2003. Can Hospitals and Physicians Shift the Effects of Cuts in Medicare Reimbursement to Private Payers? Health Affairs. October.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2010). Health Reform Implementation Timeline. http://healthreform.kff.org/timeline.aspx, accessed 16 November 2010.

Morrisey M. 1993. Hospital Pricing: Cost Shifting and Competition. EBRI Issue Brief. May (137).

Morrisey M. 1994. Cost shifting in health care. Separating evidence from rhetoric. Washington, DC: AEI Press.

Morrisey M. 1996. Hospital Cost Shifting, a Continuing Debate. EBRI Issue Brief. December (180).

Pizer S, Frakt A, Iezzoni L. 2010. The Effects of Health Reform on Public and Private Insurance in the Long Run. Health Care Financing & Economics Working Paper. VA Boston Healthcare System.

ProPAC (Prospective Payment Assessment Commission). 1992. Optional Hospital Payment Rates. Congressional Report C-92-03. Washington, DC. U.S. Government Printing Office.

PWC (PriceWaterhouseCoopers). 2009. Potential Impact of Health Reform on the Cost of Private Health Insurance Coverage. October.

Reinhardt U. 2006. The Pricing of U.S. Hospital Services: Chaos behind a Veil of Secrecy. Health Affairs 25(1): 57-69.

Starr P. 1982. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books.