Recent posts here and elsewhere about physician-patient information asymmetry made me realize that I was not aware of empirical work on the subject. Joshua Gans helped me out a little on this. And, again by email, Brad Flansbaum helped me out a lot. Among the pile of documents he pointed me to (many of which I’ve not yet read), was a Partnership for Clear Health Communications paper on low health literacy,* by John Vernon, Antonio Trujillo, Sara Rosenbaum, and Barbara DeBuono.

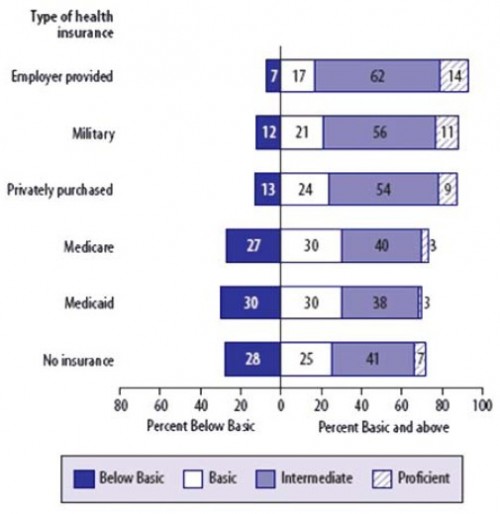

The authors use the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) — a US survey of over 19,000 adults — to assess health literacy. Based on the NAAL, here are the distributions of health literacy assessments by type of health insurance:

What does this mean? What’s “basic” or “intermediate” health literacy? The authors explain,

[I]ndividuals considered to have Below Basic health literacy would not be able to recognize a medical appointment on a hospital appointment form, nor would they be able to determine from a clearly written pamphlet containing basic information how often a person might have a specified medical test. Persons with Basic health literacy would have trouble providing two reasons why someone with certain symptoms might have a specified test, even when they used information from a clearly written, accurate pamphlet.

Individuals with Intermediate health literacy would be able to use an over-the-counter drug label in order to identify substances that might cause an adverse drug interaction. They also would be able to find the proper age range when certain vaccines might be given to children, using a childhood immunization chart. Those with proficient literacy are able to calculate an employee’s share of health insurance costs for a year, using a table that shows how the employee’s monthly cost varies depending on income and family size; they can find the information required to define a medical term by searching through a complex document and evaluate information to determine which legal document is applicable to a specific healthcare situation.

Two things are notable here. First, only a tiny fraction of the population has proficiency in health literacy. With the exception of the military, among those on publicly financed insurance, proficiency is at a 3% level. The second thing to note is that the majority of individuals on Medicare and Medicaid (as well as the uninsured) have very low levels of health literacy. Even individuals with “basic” literacy have serious deficiencies in their ability to comprehend health information, as described in the quote above. “Intermediate” health literacy does not confer a tremendous capacity to understand health care either, far less than would be required to optimally navigate our complex health system.

The authors calculate that the annual costs associated with the level of health literacy exhibited in the population range from $106 billion to $238 billion (in 2006). That is, there are large savings available through patient education. To what extent they can be realized and what it would take to do so is not clear. Note, however, that this is the savings available in increasing literacy for those in the “below basic” and “basic” ranges. I think it is safe to say that even if we did increase literacy to “intermediate” and above, physicians would still hold a large information advantage relative to patients.

And that’s not a bad thing. We go to physicians for a reason: they’ve got the expertise. Their job is to use it to assist us. That’s what they get paid for. Is the price worth the service? Ah, that’s the deep question. Not even smart physicians can answer it. Can you? (In advance!)

* I admit that this is all indirect with respect to physician-patient information asymmetry. Nevertheless, it is related, relevant, and interesting.

Further Reading

These are as noted by the authors. Since the paper is ungated, look there for full references.

Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer, and Kindig (2004) found that individuals with limited health literacy reported poorer health status and were less likely to use preventive care.

Baker et al (1998; 2002) and Schillinger et al (2002) found that individuals with low levels of health literacy were more likely to be hospitalized and to experience bad disease outcomes.

Howard (2004) estimated that inpatient spending increased by approximately $993 for patients with limited health literacy.

Baker et al (2007) found that, within a Medicare managed care setting, lower health literacy scores were associated with higher mortality rates, after controlling for relevant factors.

Friedland (2002) estimated that low functional literacy may have been responsible for an additional $32 billion to $58 billion dollars in healthcare spending in 2001. A substantial part of these expenditures is financed by Medicaid and Medicare.

Weiss (1999) found that adults with low health literacy are less likely to comply with prescribed treatment and self-care regimens, make more medication or treatment errors, and lack the skills needed to navigate the healthcare system.