A recent NEJM paper by Katherine Baicker and Michael Chernew titled The Economics of Financing Medicare travels familiar terrain in the vast kingdom of Medicare woes. You know the story: Medicare is consuming a growing share of our resources and, long-term, threatens the federal government and the wider economy.* So, let’s not retrace those steps.

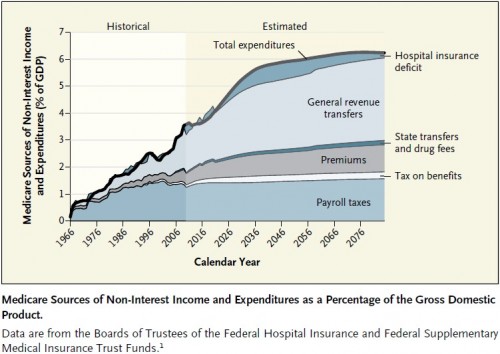

The authors include a nice chart, similar to but prettier than one published by MedPAC. (The source for both is the Medicare Board of Trustees.) It helps make a point I have made before but not in any way that helps me find a relevant old post. So I’ll make it again. (It’s possible I never blogged it.)

Notice how much of Medicare is not funded by dedicated (payroll) taxes or premiums. By eye it looks like it’s at least half in the out years. What’s special about payroll taxes and premiums is that they are dedicated to Medicare. The former is paid by current workers for current beneficiaries, the latter by current beneficiaries for themselves. So, overall, Medicare is nowhere near fully funded by dedicated revenue streams. This should not shock anyone familiar with the design of the program. It was never intended to be fully supported by dedicated funds.

This brings me to a fact about the program that has received a lot of attention. Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar, among many (e.g., Kevin Drum), expressed it in an early 2011 Washington Post piece.

Consider an average-wage two-earner couple together earning $89,000 a year. Upon retiring in 2011, they would have paid $114,000 in Medicare payroll taxes during their careers. But they can expect to receive medical services – including prescriptions and hospital care – worth $355,000, or about three times what they put in.

(More, related analysis by Eugene Steuerle and Stephanie Rennane.)

Shocking? Hardly. The Medicare payroll taxes were never designed to support all of one’s future health spending, let alone that of current beneficiaries, as the figure above shows. So, while it is true that the hypothetical average-wage two-earner couple don’t fully fund their future Medicare benefits, it doesn’t reveal any new flaw in Medicare financing. It merely reveals a feature (or bug) built right into Medicare from inception.

In fact, because of its more progressive tax structure, one might argue that financing more of Medicare via general revenue is the right thing to do. In other words, maybe that average-wage two-earner couple should be paying an even smaller share of their future Medicare spending via payroll taxation.

Back to the Baicker/Chernew paper, I’ve got one minor warning to readers of it. They write,

[R]aising taxes to pay for public insurance exerts a structural drag on the economy even if the revenue is spent on care; the same is not true of unsubsidized, privately purchased care or insurance.

First, note that they are not saying that privately funded care or insurance exerts no structural drag the way tax-financed, public insurance does. They are saying that unsubsidized, privately purchased care or insurance imposes no drag. Since the vast majority of health insurance, if not health care, is taxpayer subsidized (the employer-sponsored insurance tax subsidy counts as, well, a tax subsidy), there is very little unsubsidized, private care or insurance in the US. Moreover, I’ve heard of no serious reform proposal that does not involve subsidies of some form. Baicker and Chernew are not praising any significant facet of our system that exists or is proposed to exist.

However, is it true that unsubsidized, privately purchased care or insurance would exert no structural drag on the economy? It is well understood that the private medical care and insurance markets are not perfectly competitive and suffer a variety of market failures. For these reasons, among others, people are priced out. People are locked into jobs. Consequently, there would be (and currently are) significant welfare losses that subsidization seeks to address. It can therefore be argued that these markets, even when unsubsidized, pose problems for the economy. So, I have some trouble with the sentence quoted above. But it is just one sentence and not key to the point of the paper. Let’s move on.

The paper wraps up with a paragraph that would be hard for anyone to disagree with:

Although Medicare provides invaluable financial protection and access to care for almost 50 million beneficiaries, there’s a limit to what we can finance with limited public resources — public programs cannot pay for all possible care for all people. Different plans for limiting Medicare’s public resources impose risk on different stakeholders: bundled payments shift financial responsibility and risk to providers; fixed premium support shifts them to beneficiaries. Ultimately, benefit and payment structures must be improved in a clinically informed way that’s consistent with high-value care but that also moderates spending growth to keep the program — and the economy — afloat.

But, of course.

*Aside: It’s a bit unfair to blame Medicare for this, as growing health spending is a health system wide problem, but the subject of the paper is Medicare and what’s true system wide is true of that program.