This article is part of an educational video series created by BUSPH student, Tasha McAbee, and health economist, Dr. Austin Frakt, to explain the intersections of economics and health. The transcript follows the video below, which can also be found on YouTube at Health Economics Explainers.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a sudden and drastic rise in unemployment.

For most non-elderly working individuals in the United States, losing employment means also losing, or at least disrupting, their access to affordable health insurance. As a result, the pandemic resurfaced discussions about our long-standing relationship with employer-sponsored insurance. Is it time to sever that tie? What would happen to individual costs if employees no longer got health insurance through their employers?

The employer sponsored insurance system that accounts for half of the US population’s source of health care coverage began in the late 1920s when a small proportion of employers assisted people struggling to cover rising healthcare costs. Then, during World War II, employers were unable to increase salaries due to a federal freeze on wages, so, instead, more of them began offering assistance with health insurance as a benefit to their workers. In 1943, the IRS made this benefit tax-free, meaning employers and employees kick in money for coverage before it is hit with federal income and payroll taxes. This “tax subsidy” effectively makes insurance cheaper, but it has other effects that are problematic.

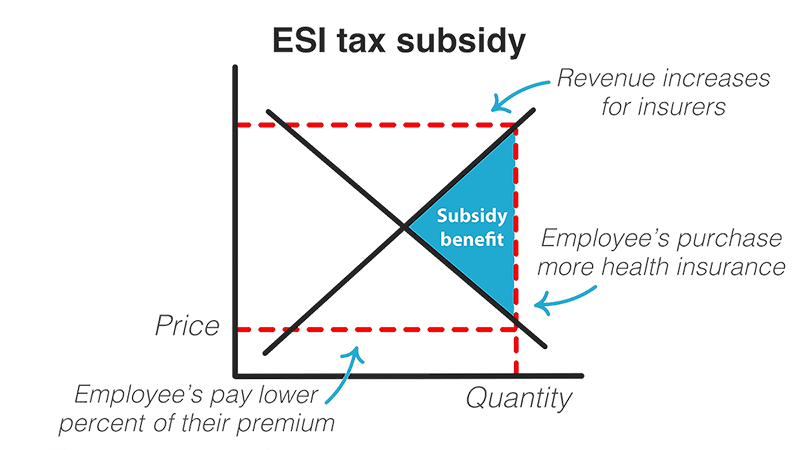

What exactly is a tax subsidy and how does it work? Principles of economics tell us that in a competitive, free market, the price of a good or service, in this case a health insurance plan, is determined by the market equilibrium, where supply meets demand.

The tax break is a subsidy that allows the price offered to consumers to decrease — because the government is picking up part of the tab. And when consumers’ prices drop, the amount of health insurance purchased increases. In the case of health care coverage, more employees purchase health insurance plans through their employer.

This, in turn, increases revenue to insurance providers. They, along with the employer and the employee benefit from the subsidy.

The savings are substantial – an estimated $303 billion in 2021 alone that would otherwise be taxes. To put this in perspective, the government could fund universal paid family leave for an entire decade with just $225 billion. In addition to this large loss in federal revenue, there are other problems with the tax subsidy. One is job lock, where people feel they cannot leave a position due to the risk of losing their access to affordable health insurance. Another is inherent inequity in the system — the employer sponsored insurance tax subsidy does not benefit everyone equally.

Because taxes are percentage-based calculations, those with higher wages benefit more from this system. Take for instance, two employees, both part of their employer sponsored health insurance plan that includes a $1,000 monthly premium before the subsidy is taken into account. Once the tax break is applied, the lower wage employee, who falls in the 12% income tax bracket saves $254, paying $746 while the higher paid employee saves $347, only paying $653.

Said another way, the subsidy compounds the inequality faced by lower-income workers, who are already paying a higher percentage of their income on health insurance than higher-income workers. In 2017, those earning around $40,000 in annual income paid around 14% of their income on health insurance, in premiums and out-of-pocket costs combined, while those making over $80,000 only had to put 4.5% of their income towards health insurance.

Not only that, but the disparity between low and high income workers is widening, just as overall employee contribution to health care expenses is increasing at a higher rate than employer contribution, wages, and inflation.

There are problems with our current system and in general with tying health insurance to employment. But if we get rid of the subsidy benefit, wouldn’t our individual health care costs and premiums rise? While it’s true that if the employer sponsored insurance tax subsidy disappeared, the price of health plans would return to market equilibrium, there are other ways to subsidize coverage without going through employers. This is what the Affordable Care Act aimed to achieve by offering individual subsidies through the public marketplace for health plans. These tax credit subsidies similarly work on a sliding scale based on annual income, but flipped around from the employer sponsored insurance tax subsidy. The ACA tax credits are designed to benefit low-income individuals more, instead of benefiting those with higher wages, as with employer sponsored insurance. The lower one’s income, the greater the tax break, and as of 2021, there is no income cutoff on eligibility for a subsidy.

If you take our example from earlier, comparing two people, each with a $1,000 premium, the lower wage employee pays a smaller percentage of their income for health insurance than the higher wage employee under the ACA’s tax credit program.

While removing the tax break on employer sponsored insurance would, by itself, increase the cost of coverage to individuals and families, the government could then use that large sum of money to help people cover costs in a more equitable way that doesn’t tie coverage to employment. And as we saw with the Covid-19 pandemic, there are plenty of reasons why we may want to someday make this kind of change.