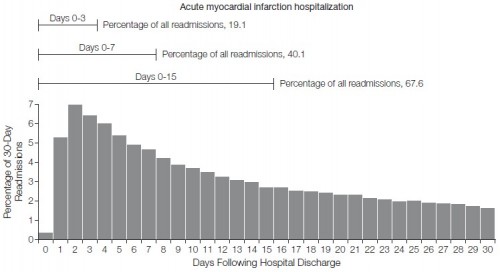

The recent JAMA paper by Dharmarajan and colleagues includes an analysis of the distribution of FFS Medicare-reimbursed hospital readmissions by day after index visit discharge. They examine patients discharged with diagnoses of heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia. Here’s the AMI distribution:

The proportion readmitted within one week is shockingly high, 40%. (For heart failure and pneumonia it’s 32% and 34%, respectively, which is still pretty shocking.) Almost 20% are readmitted after three days. This is disturbing. The argument that institutions have no business discharging patients who can’t stay out of the hospital for a few days is hard to counter. If they aren’t at least that ready to go, maybe they shouldn’t go. This, perhaps, is exhibit A for proponents of penalizing hospitals for short-term readmissions. They must be doing something wrong.

We found that a high proportion of 30-day readmissions occurred relatively soon after discharge, which may explain why hospitals least likely to provide outpatient follow-up within 7 days after hospitalization for HF had the highest rates of 30-day readmission.[44] The preponderance of early readmissions may also explain why exclusively outpatient interventions have often been ineffective in reducing 30-day readmissions that may have occurred before initial follow-up.[42-43] In contrast, strategies involving the combination of inpatient and early outpatient interventions with the use of tools that facilitate cross-site communication have lowered readmissions that occur soon after discharge.[45-46] However, because about one-third of 30-day readmissions occurred during days 16 through 30 after hospitalization, many patients require substantial attention well beyond the initial follow-up visit.

And still, it is not unreasonable to ponder some of the questions raised by other work I’ve summarized recently:

- How identifiable are patients who are at high risk for short-term readmission?

- What proportion of these readmissions are preventable in general and preventable with means under hospitals’ purview in particular?

- How do readmissions relate to socioeconomic status or type of hospital?

- What interventions are proven successful and generalizable beyond the setting in which they were tested?

- Might some interventions actually increase readmissions?

- What is the relationship between readmission and mortality rates?

Once one really gets into the weeds, penalties for readmissions don’t look like the slam dunk the chart above suggests they are. That is not to say that we shouldn’t incentivize hospitals and health systems to do a better job with health care setting transitions. That’s not the debate. The question is, how?

Dharmaraja, et al. also examine readmission diagnoses and their relation to age, sex, and race.